The pictures are heartbreaking, the statistics are mind-boggling. And, incredibly, it’s still getting worse.

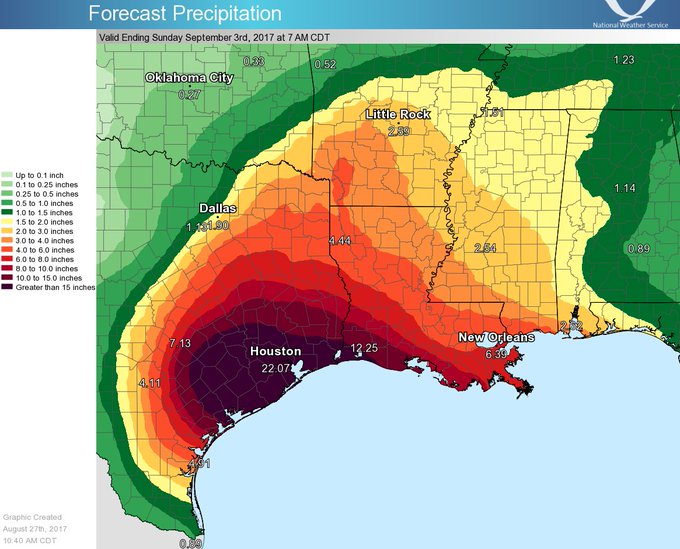

Since Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Texas late Friday night, more than 40 inches of rain have fallen in parts of the Houston metro area, producing the worst flood in the city’s modern history. The latest forecasts show another 15-25 inches on the way before Harvey clears out of the area on Wednesday. Harvey is sure to rank as the worst rainstorm in U.S. history, according to an initial analysis from the Texas state climatologist.

“Of course I’m surprised,” Houston meteorologist Tim Heller told Grist. “We tell people to prepare for the worst, but this is worse than the worst! This isn’t isolated flooding, this isn’t neighborhood flooding, this is area flooding, regional flooding. The warnings were there for 15-25 [inches] of rain, then 30, then 40. I quit giving out storm totals because I’m not sure what we’ll end up with now.”

The amount of rain so far brings new meaning to the word “unprecedented.” In just three days, Houston doubled the previous record rainfall for a full month — 19.21 inches set in June 2001 during Tropical Storm Allison (which caused the city’s previously worst flood).

So much rain has fallen that the National Weather Service had to add additional colors to its maps, in order to show rainfall totals this huge. During the peak of the rainfall on Saturday night, the local NWS office in Houston ad-libbed a dire warning and issued a “Flash Flood Emergency for Life-Threatening Catastrophic Flooding” — the first time the already-dire “Flash Flood Emergency” was considered insufficient to describe the impending risk.

All weekend, there were impromptu water rescues made by people in kayaks and inflatable rafts. A viral image showed a dozen people in a nursing home, water up to their hips, awaiting rescue. (Eventually they were airlifted to safety.) These kinds of scenes evoke painful memories of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

According to a preliminary and informal estimate by disaster economist Kevin Simmons of Austin College, the aggregate cost of damage and lost business associated with Hurricane Harvey “will likely exceed Katrina.” That means Harvey could ultimately cost between $150 billion and $200 billion, even more if the floodwaters significantly expand.

Nearly every river and stream in the Houston area is experiencing record or near-record flooding. Buffalo Bayou, the main waterway through downtown Houston, is expected to rise an additional 11 feet by Tuesday night. Texas Governor Greg Abbott has mobilized the entire Texas National Guard to assist with the response.

While Harvey’s rains appear unique in U.S. history, heavy rainstorms are increasing in frequency and intensity worldwide — a clear sign of climate change. A warmer atmosphere can speed evaporation rates and hold more moisture, and Harvey’s flood comes via a firehose of intense thunderstorms spawned off a warmer-than-usual Gulf of Mexico. The increasing intensity of rainfall in the Houston area is only part of this problem, though: Unchecked development has added dozens of square miles of pavement to the swamps and prairies surrounding the city, channeling additional floodwater into homes. That means Harvey is a storm decades in the making.

But Harvey’s wrath is on a whole new level. This is the scale of disaster that will redefine the course of the entire region, and linger in the country’s consciousness for years. It will provide an opportunity to rethink Houston, the fourth-largest city in America. And, hopefully, mark the first step on a path toward a more resilient future.