The problem of climate change has become a part of the current global discussion, due to the Paris Accord. Current mainstream arguments focus on three specific components of the problem:

- the disputability of global warming,

- the relevance of anthropogenic contribution, and

- the extent of the dangers associated to an increase of the global temperature.

Key players appear to have difficulty moving the discussion past these three components of the problem, towards potential solutions. Instead, the discussion returns again and again to describing the problem, in greater and greater detail, with arguments stalling on various small pieces of the problem. Our inability to move past the problem to solutions is based in part on how the various critics frame the discussion. Critics on both sides of the issue are subject to a framing effect, where the we house the problem mentally within the boundaries of the human economy.

While opponents of climate change suffer from their own framing effect, this post focuses specifically on the proponents’ framing effect. Those who advocate for policies to limit change make four main assumptions that impact their thinking:

- Those concerned about the climate place the environment either within the global human economy, as a subsystem, or externally, where it can be used at will, endlessly. As a corollary to this mindset, the problem of climate change is an anthropogenic problem caused by humans, with no real impact on our resource base, which is either external to the system and infinite, or internal and thus, not critical to our life support.

- Because the human economy is more important than the environment, societal economic growth is an inviolate mandate for all countries. The assumption is that we can support economic growth while solving the problem of climate change.

- Globally politicians have the will and options to create viable, effective actions that limit the temperature increase without harming economic growth.

- We can use technology to find suitable solutions that will eventually handle, if not overcome, most of the problems. Moreover, added technology does not use added energy or environmental resources.

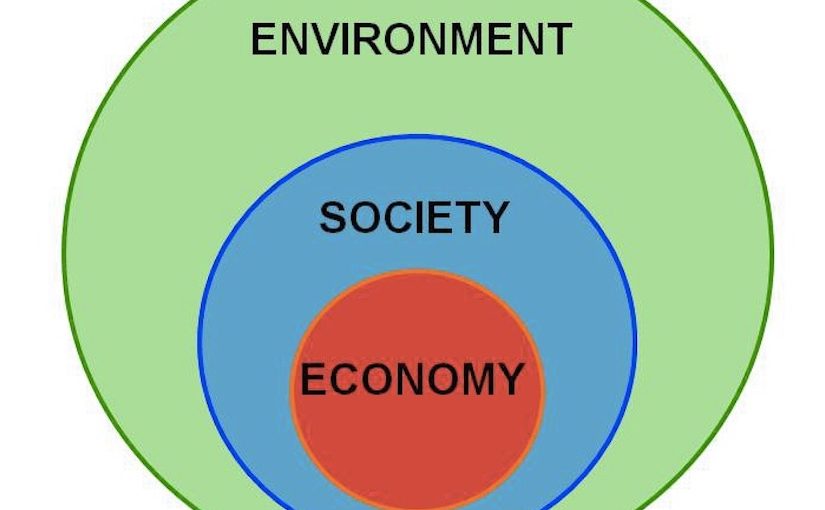

Unfortunately, these postulates are false. While the first postulate suggests that the environment is either an unnecessary subset or an externality to the economy, the real world tells us the opposite. The environment is not an element (subsystem) of the economy/finance role-playing game. The economy is actually a subsystem of society, which is embedded in the geobiosphere, its super-system. From a systems perspective, any rearrangement of the geobiosphere as a result of new driving forces, including anthropogenic emissions, affects the behavior, the stability and the sustainability of the global economy as a subsystem.

Economically based choices do impact the environment, but the geobiosphere then re-adjusts its operation (somewhat unpredictably) and impacts the behavior of the global economy itself. Any hope to make significant changes to the global environment (the super-system) while at the same time keeping the operation of our economy fixed or expanding is inconsistent with systems thinking. But this seems to be exactly what people are trying to do, by trying to freeze the current status of the environment as a provider of raw material and ecosystem services that can guarantee economic growth.

This brings us to the second postulate. The idea that growth can stay the inviolate primary focus of any policy planning relies on faulty epistemic foundations. The mandate for growth has been embedded in the assumptions of sustainable development. But at this stage, further societal growth is incompatible with the maintenance of a livable geobiosphere. As long as we struggle in the name of growth to keep economic development, which is a feature of the economy as a subsystem, there will be no room for sustainability, which is a feature of the whole super-system, the geobiosphere.

The third and fourth assumptions are related. Proposed actions usually focus on a composite list of high-level political commitments, voluntary agreements, subsidies, and financial measures, without directly impacting the activities that are responsible for emissions. In general, the measures proposed to combat climate change are various societal political experiments made popular by the Kyoto Protocol, experiments whose only effect so far have been to show their own ineffectiveness.

The figure below illustrates a few of the major global protocols and agreements of recent decades regarding environmental indicators for geobiosphere health such as CO2 emissions, deforestation and biodiversity, showing how the general trends have been insensitive to any initiative. The stubbornness with which we pursue top-down “road of treaties and commitments” are then inversely proportional to their impact, leading to the legitimate question whether this is due to ill-placed faith in top-down approaches, within a hyper-capitalist system, or just lip-service. Unfortunately, the real circumstances suggest a combination of the two.

As a matter of fact, the promoted actions have led to some reduction in emissions either as a side effect of the preservation of economic efficiency through local and global growth and trade, or as a function of slowed growth due to peak oil. The recent decision to abandon the Paris Accord by the United States fits perfectly well with either scenario. Casting blame for failure of the agreement on a single leader distracts attention from the real weakness of the Accord itself–its systemic inconsistency. Finding scapegoats to blame is a comforting narrative that a global policy really exists to challenge climate change, allowing us to continue business as usual.

The framing of our climate arguments creates cognitive dissonance. Our inaccurate assumptions protect our way of life, but those assumptions create cognitive dissonance when it comes to climate change policies. The world as we frame it is full of well-meaning politicians and economists, who are sincerely struggling to find solutions favorable to everyone. Instead, the real world, where we all live, is composed of powerful, global corporations lobbying for the retention of global activities that are wrecking the planet.

As a matter of fact, the economies and corporations that control the extraction, trade and use of fossil fuels promote a globalized society bent on further expansion of global retail trades whose primary goal is profit, which mandates burning more fuel. This burning fuel is recognized as the main anthropogenic source to the greenhouse gas emissions.

Our framing and cognitive dissonance prevents us from moving forward with useful policies to restrain climate change. Solutions that protect growth are either destructive to the geobiosphere and/or intensive in energy use. But we have a conceptual scientific framework that explains our societal systemic behavior exists, the Maximum Power Principle. H.T. Odum derived it from the pioneering work by A.J. Lotka, who first indicated the maximization of useful power as the driving force behind natural selection. Odum extended it to a systemic principle, stating that systems that prevailing in competition are those that develop feedbacks in resources flows that increase energy inflows and output. This means that countries will continue to strive towards burning all available fossil fuels, either usefully or not, in a competition towards more growth. Maximum power is the systemic feature we need to devise policies for.

Global measures to slow warming would limit or change economic activities such as mining and extraction, transportation and trade networks, deforestation, livestock, and land allocation. Understanding of the Maximum Power Principle could lead to policies for a relatively prosperous descent. But as long as the our politicians support the goal of economic growth, the geobiosphere will continue to pay the bill for the activities of its subsystems, eventually forcing a disruptive collapse of the subsystem itself.

The only effective political measures will address the entire system, the geobiosphere. Whatever we do will impact the geobiosphere, and the economy, as a subsystem, will be impacted and have to adapt itself to these global changes. To develop an effective global policy about climate change, the time, means, and will are necessary. Which of them have been lacking so far, and why? As Donella Meadows suggested, we can glean the purpose and goals of a system from its behavior, not from rhetoric or stated goals.

Images by the author, Dr. Francesco Gonella, from the original article at The Prosperous Way Down website.