All photos by Paige Green.

Rain clouds linger above, but they do nothing to dampen the excited voices of those gathered below. Today is Shearing Day at Duckworth Farm and everyone from teenagers to retirees has come to lend a hand.

There’s Jasper, a fifteen-year-old with bright blonde hair, who recently helped pick blueberries and couldn’t wait to return. Next to him stand Rachel and Briana, two new additions to the farm’s WWOOF program, a global initiative connecting volunteers with opportunities to live and learn on organic farms.

“Before this I was a potter and a dancer. Now I’m here to get closer to nature,” grins Rachel.

“I was in advertising and banking,” shares Briana. “But now I’m studying to be a holistic health coach.”

This is Duckworth Farm’s fifth year participating in WWOOF. Of the 300 international applications they received this season, only 20 were accepted. Rachel and Briana were lucky to get a coveted spot, and though they’ve only been here for less than a week, the girls are already being thrown into the thick of it—and embracing the experience.

“I can’t wait for the shearing to start!” says Rachel.

Volunteers continue to arrive in a steady stream. Neighbors, friends of friends, and even a few customers. “It’s going to be a great day,” proclaims longtime friend Liz. A slight drizzle descends and she gamely pulls a red ball cap adorned with flowers over her bobbed grey hair.

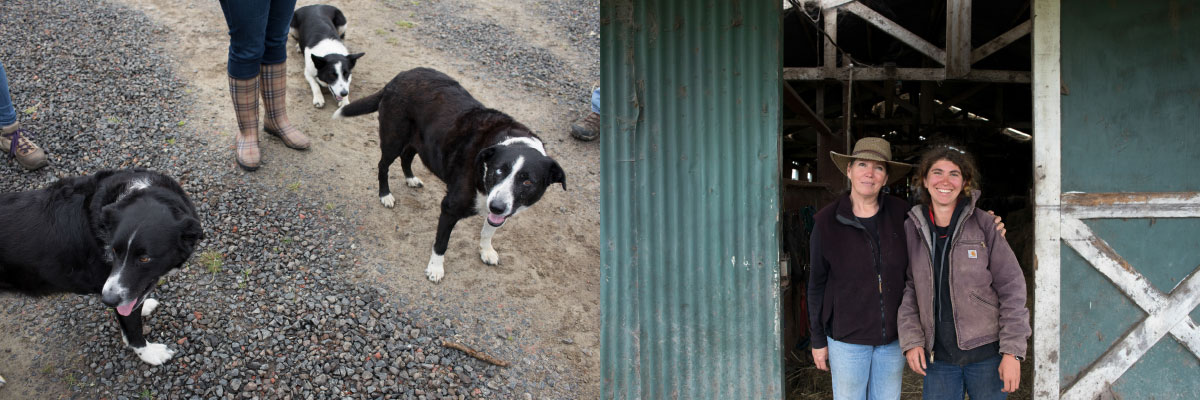

In the distance, a woman strides down the gravel drive, trailed closely by three McNab sheepdogs. Her chestnut hair is pulled back in a loose bun and her face is shaded by a wide-brimmed hat. The energy in the air peaks. Lorri Duckworth has arrived.

“Welcome!” she calls out with a huge smile. Immediately compliments begin on the scarlet and gold scarf around her neck.

“I made it myself,” she laughs, stretching it to show the stitch work. “And I’ll be able to make more after today is done! Now, who’d like a tour before we start?”

Dotted with ponds and brimming with wildlife, Duckworth Farm is 82 acres of secluded paradise. The entire property is open, save for a fence in the back protecting a relic Black Oak forest. “Just being here is a look back in time—at how this county would have looked 150 years ago,” explains Lorri.

Wild plum trees sway in the breeze and a Black Crowned Night Heron takes flight as the group makes its way to a line of spacious tents propped on raised concrete slabs. The canvas flaps of the first tent are pulled back, offering a glimpse of a loom, bed, desk and antique sitting chairs. This is where the ‘WWOOFers,’ as they are affectionately called, will set up home for the late spring and summer. There’s a fire circle for nighttime chats and a serene pond equipped with bubblers to keep it clean for swimming year-round.

“People may think that one woman on one farm cannot make a difference. I am just a drop in the Sea, however, these students come and learn and change, then they leave and become another drop in the Sea, then they teach and we have more drops in the sea, with enough drops you become a storm and that’s when you can start to change things. We teach them how to do everything. Welding, farming, carpentry, how to drive a horse trailer. See that building over there? They built that themselves. One of the kids did all the plumbing.”

She’s pointing to a shower house, equipped with an outdoor, vintage clawfoot tub for soaking in nature.

“But it’s not all serious, laborious work. We have an ex-NASA physicist coming to teach juggling. And local artist Susan R. Ball will be teaching plein air painting. And Mike Brookfield, a local farrier who teaches how to rope and work a forge — he’s a true American cowboy. It’s marvelous!”

Around the bend from the WWOOFer’s quarters are rows and rows of certified organic blueberry bushes. Lorri stops and holds up a hand.

“Listen. Can you hear the three bumblebees?” she asks.

“Three? That’s really specific,” someone laughs.

She smiles.

“Yes, three.”

Her philosophy is to keep things simple, and part of that includes protecting the delicate balance of nature already present at the farm. There are no beehives on the property, she tells the group, because it would harm or displace the native bumblebees. One bumblebee can do the work of thousands of bees. Why mess with it? The lower half of the property is left fallow so the bumblebees can settle there, and they in turn pollinate the delicious blueberries that Duckworth Farm is known for.

“Food is music! You should experience a floral melody. There should be high notes, and low ones, too. The bumblebees make that happen.”

Across from the blueberries, one of the volunteers notices tufts of wool wound around a line of tree trunks.

“Oh yes. Instead of using wire, we experimented and discovered that bits of wool do just as good of a job keeping the sheep off the trees. Something about the smell,” says Lorri. “And it biodegrades naturally, which is a bonus for us.”

This approach, as becomes evident, is prevalent throughout the entire farm. Walking towards the chicken coop, Lorri cranes her neck to look up into the trees.

“For a while we were losing our chickens to hawks, who live right there.” She motions to a cluster of tall trees to the left. “But then one of the kids told us that maybe the ravens, who live over there”—she points to the right—“could help us out.

“As a test, we gave the ravens a daily offering of two eggs and sure enough they started to swoop down and scare off the hawks if they came too close to the chickens. It was amazing—and it worked!”

She pauses and whispers in a conspiratorial tone.

“We just have to keep doing it. The ravens have become their own version of the mafia. If we forget, they go in and get what they’re owed.”

Moving past the chicken coop—which is made from all recycled and salvaged material, including an old trailer with solar panels—there’s an artisian spring and a cluster of buildings. The first is the home of Lorri and her husband Oscar, complete with a porch and pair of rocking chairs overlooking the pond.

“It’s like waking up to a dream,” she says, beaming. “I’ve wanted a farm since I was eight years old, and on a blind date at sixteen I shared exactly what it would look like. That blind date happened 38 years ago, and I’ve been with my husband Oscar ever since.”

The pair purchased the farm 15 years ago, after almost a decade of searching. Lorri was on her way to view a prospective property in Petaluma when she realized she forgot the address. A few wrong turns later, she found herself at the gates of the future Duckworth Farm. The previous owner, Bud Nahmens, “liked the idea that another family with children would want to put the farm back into production. We made him an outrageous offer… and he accepted the next day.”

Bud, who was born on the property in 1931, remained an important fixture in their lives until his death. “He was the father I should have had,” reminisces Lorri. “I got the tractor stuck in more ways than even I could imagine. No problem, I would just call him and he would show up, smile his wry smile, shake his head, and ask how I did it. I have no idea how many times he pulled me out of the mud.”

When Lorri decided to grow hay and plant blueberries, it was Bud who accompanied her to meet with the county to inquire about logistics. He fervently believed that Duckworth Farm would be a success. And he was correct. It has become a working farm again and so much more.

Down the road from the farmhouse is a renovated dairy-house-turned-workshop. Topped with exquisite cupolas—Oscar, who is an engineer, drew and built them to scale off a photo Lorri admired—the place is an Americana collector’s dream. Lively music plays within the large space, which is filled with vintage cars, arcade machines, hubcaps, engines, tools and all sorts of unique bric-a-brac. The soaring rafters are painted blue like the sky, and this is where the WWOOFers learn to build and repair their own bicycles. “That’s how they get around,” remarks Lorri. And parked right outside the workshop’s side doors is Duckworth Farm’s signature 1935 Dodge Bros’ burgundy truck, which hauls crates of plump blueberries to market at the beginning of the season.

The rising sound of bleating sheep quickens Lorri’s steps. Preparations for the shearing are almost all in place, so there is only time to quickly duck into the spinning room. Large copper doors, patinated with age, swing open to reveal looms and a sewing table strewn with projects in different stages of completion. In the back, a spiral staircase leads to a loft perfect for dreaming up craft projects.

In this room as with everything—from the WOOFer’s grounds to the chicken coop and workshop—Lorri’s design philosophy of ‘form, function and (she emphasizes) free’ is on display. The couches are from an estate sale and the cabinets were found, along with the copper doors. There’s a 100-year-old sock machine Lorri stumbled upon, as well as an authentic Flying Shuttle Loom that sent her on a 22-hour trip to Oregon to retrieve it. Salvaging, reusing and bringing old machines whirring back to life are core values of Duckworth Farm, and they are evident everywhere one turns.

As part of the program, every WWOOFer learns to drop spindle here, beginning with rag rugs. For others in the community with an interest in learning traditional crafts, Lorri’s daughter, Snazzy, hosts Thursday Fiber Nights that are open to the public. These get-togethers are a new take on the knitting circle concept, replete with small-batch ice cream (made by Snazzy), cupfuls of tea, and patterns that take beginners from sheep-to-shawl in no time.

Outside, the buzz of an electric razor is heard coming from the barn. Shearing has begun, and while Lorri oversees the main activities of Duckworth Farm, the moment the group steps into the shearing barn they are in Snazzy’s domain.

Snazzy Duckworth, who named herself at age three, is leaning over the stall to watch as John Sanchez, one of the best shearers in Northern California, does his work. She’s in her mid-twenties and has thick, auburn hair. When a fleece is tossed over to be examined, she immediately rattles off the name of each sheep.

“That’s Belle,” she says of a curly, tan fleece. “And the one coming up is Ali Baba.”

While wool has become a growing side business, Snazzy has her sights on moving Duckworth Farm towards becoming a certified organic sheep dairy. She’d like to sell her ice cream, as well as cheese and milk. “Banana bread and blueberry are my specialty flavors,” she grins. Continuing to think ahead, she’s also purchased sheep genetics from Australia to diversify and strengthen the genetics of her flock.

“The sheep thrive under her care. She’s very smart—and humble,” shares Lorri. “We told our kids they could get whatever University degree they wanted, but they needed to pursue a vocational degree first. Something practical. Before she finished high school, Snazzy already had her culinary degree, and then went on to graduate with degrees in natural resources and waste management.”

“She’s also the jewel of the race track,” pipes up Liz with the flowery hat.

“That’s right,” nods Lorri. “She’s a race car driver at the Petaluma Speedway.”

A modern shepherdess who races cars and whips up ice cream? Dancers and engineers who’ve left the stage and lab to drive tractors and pick blueberries? Even Liz, it’s soon discovered, holds the title of the first female river guide in California. For the group gathered here today, eclectic passions and diverse skill-sets are the norm. And shearer John is no exception.

When he isn’t seamlessly catching and shearing up to 170 sheep per day, John is an autoimmune nutritionist. After a challenging battle with Lyme’s disease, he became intrigued with eating psychology and its effects on healing. To treat patients, he believes understanding their life experience is essential. It’s a holistic approach that he also applies to his work with sheep.

First, John connects to the animal and notices its energy and tendencies.

“I dance with the sheep. They direct the next move,” he says with a chuckle. “I change my pressure and position based on their signals. I don’t force anything.”

Muscular and tanned from the work, John has been shearing sheep for 23 years. He learned from his father and has finessed a much-lauded process that has him busy all spring and summer.

“I enjoy it because there’s a physicality and a grace to it,” he says.

And today, everyone at Duckworth Farm has the chance to be both spectator and participant in his work. While John selects one of the sheep and begins to shear—always starting at the belly and pulling skin taut for a quick and close shave—the previous fleece is retrieved by Jasper and flung onto a large makeshift table. At least five pairs of hands go to work, looking for caked dirt or loose fiber to pull off the edges. When a fleece is deemed clean enough, it’s folded like a jelly roll, bagged and labeled. The process moves swiftly, as Jasper gets good at unfurling the wool and most of the fiber requires little inspection.

“Since our sheep are free and not confined, they tend to be cleaner,” explains Lorri. “They roam all over the place, getting what they need. And we haven’t lost one yet, despite not having any fences. The dogs do their job well.”

“How many sheep are there?” someone inquires.

“You know, I started counting and fell asleep,” says Lorri with a wink.

Snazzy confirms that the count is around fifty, with current breeds ranging from Shetland and Romney to Lacaune. The wide array of wool colors and textures on display delights the group.

“Look at this bushy one!”

“Like a bear!”

“You’re right. A grizzly—that’s what it looks like!”

A particular fleece with gradations of red and tan instantly garners comparisons to Snazzy’s hair. And when the fleece of Old Girl (formerly known as Ivy) is laid out, Lorri sighs contentedly.

“We’d been on the farm less than 60 days when we brought home three sheep. Old Girl is the last of those three, and she’s become more of a pet. On a typical day, you’ll find her relaxing and sleeping on the stairs of our house.”

At this point, the fingers of all the helpers are shiny and moisturized from the lanolin of the wool. It’s a happy, charged atmosphere. A squawking goose charges in and has to be carried out. There’s constant chatter about the farm and community news. It’s what one would imagine the barn-raising days of yore to be like, alive and well at Duckworth Farm.

With the first half of the sheep done, there’s only Gilderoy the ram to be brought in before lunch. He proves to be a handful, requiring Snazzy, Jasper and a few others to hold tightly to his tether as they guide him inside.

“He’s in his terrible twos,” comments Lorri, but John manages him without much difficulty.

Tired from a morning’s hard work, the group heads up to the cookhouse for nourishment. Inside, a long farmhouse is laden with a steaming pot of carrot soup and trays of sizzling nachos. Everyone eagerly sits down and tucks in, a quiet satisfaction stealing over the room. The walls and ceiling are painted five different shades of soothing green, encouraging an environment of peace.

Lunch has been prepared by Rachel and Briana. During their stay, WWOOFers are responsible for all the meal planning and cooking, which they do from scratch. No food is processed or stored in boxes. Everything is decanted into glass jars.

“I want them to look at ingredients as possibilities, not products,” says Lorri.

To improve their skills, WWOOFers get the chance to cook on a white O’Keefe & Merritt Retro Classic stove, with a place for bread proof and ample burners for trying out multiple dishes. Lorri bustles between the stove and kitchen island, mixing dough to make up a quick batch of tortillas.

“It’s really very easy,” she assures Jasper, who’s helping fry them.

Sunlight begins to peek through the clouds, casting a warm glow on the kitchen garden glimpsed out the back windows. This garden is under the complete care of the WWOOFers, who decide what to plant and harvest for their meals.

“Our farm is created by everyone who comes,” says Lorri. “It’s made up of the hard work and dreams of many. During the application process, we don’t just look at what you’ll give, but what you need. That is more important to us. We may be a drop in the bucket, but whatever you do here, you will succeed.”

There’s an echo of Bud in her words.

She transfers a few warm tortillas to a plate and brings them to the volunteers, who take one last bite before joyfully returning to the barn for round two of shearing.

There comes to mind an old Indian proverb: “All the flowers of all the tomorrows are in the seeds of today.” Duckworth Farm, it’s clear, cultivates more than blueberries. It raises more than sheep, and grows more than hay. It nurtures creativity, responsibility and collaboration for all who pass under its wide-open gates.

Here, all the seeds that arrive blossom, and leave to take the world by storm.

To learn more about Duckworth Farm, visit them on Facebook & Instagram, and look for their local blueberries in Sonoma area markets.