Despite the US’s recent withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord, governors and mayors around the country continue working to mitigate and build resilience to climate change. As both policymakers and the public increasingly recognize the role of food and agriculture in intensifying climate change, many parties seek to address the food-climate connection. Fortunately, local and state policies and practices can do exactly that. Here’s what’s already happening, and what to strive for.

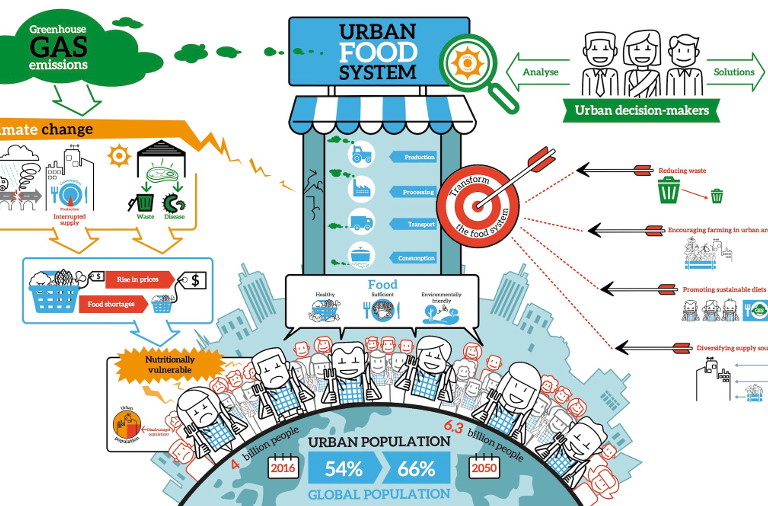

First, let’s review. The food supply chain—which includes the production, processing, transport, packaging, cooling, heating, and decomposing in the landfill of foods—contributes about a third of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Within the food system, agricultural production has the largest climate impacts; livestock represents the majority (~70%) of these emissions. This is why scientists are concerned that if global demand for meat and dairy products continues to rise as projected, the most severe and irreversible climate change scenarios will be unavoidable, even with dramatic emissions reductions across energy, transportation, industry, and other non‐agricultural sectors. Despite this evidence, agriculture and dietary consumption have been almost entirely absent from climate action written commitments worldwide, from national to local levels.

What would it look like if we incorporated food system issues into climate action plans? And how are food policy groups and governments contributing to or taking action with those plans? In conjunction with our webinar on tackling resilience through food policy councils, here are some strategies that food policy councils could begin to explore at their local, state, or regional levels.

To reduce contributions to climate change (mitigation):

Facilitate a shift to more plant-based diets

- Local and State Procurement Policies— For institutions over which they have influence (e.g., schools, agencies), encourage governments to make changes in their purchasing guidelines to include a minimum amount of sustainably and ethically produced plant-based menu options. As an example, Oakland (CA) Unified School District has reduced the amount of animal products it serves by nearly 30%, which has yielded both economic and environmental benefits. Friends of the Earth will release a report this summer with further examples of how municipalities can advance specific climate-friendly public procurement strategies. Health Care Without Harm’s new Redefining Protein report may also be useful in guiding how institutions should modify purchasing when reducing and replacing meat. (While many may be tempted to focus on procuring more locally-produced foods to reduce “food miles,” in terms of climate impact, what’s more important than reducing food miles is making a change in the types of foods people eat and how those foods are produced.[i] Avoiding red meat and dairy one day a week reduces GHG emissions more than eating locally all the time).

- Farmer support— Advocate for state agricultural departments to provide support (e.g., start-up capital, loan forgiveness, land access, tax credits) and training to new and beginning farmers who focus on specialty crop production (includes legumes and vegetables). Offer similar support to other current farmers who want to transition to such crops. There are not enough vegetables and legumes in the current US food supply (including both domestically produced and imported food) for Americans to meet recommended daily allowances; if advancing a wide-scale shift to a more plant-based diet, we will need to substantially increase our supply of these foods.

- Provide public and policymaker education about the environmental and health impacts of the production of different foods and the consumption of various diets; how the food system and farmers could be impacted by the effects of climate change; and how food security is linked to dietary choices. Mayors could sign pledges of support to encourage more plant-based eating, such as a municipal Meatless Monday resolution. Food policy council member organizations (possibly Extension, non-profits, or schools) could promote plant-based cooking classes, meal plans, and recipes. Federal nutrition programs that are administered on the local level (including SNAP and WIC) have been encouraging the consumption of produce and legumes among low-income consumers for decades, and may be enhanced with an influx of support and enhanced messaging for the general public (Turin, Italy offers a particularly interesting example). If we’ve learned anything about changing diets, it’s that multi-pronged approaches are most successful because, while knowledge is important, without enhancing people’s habits and skillsets, they will have limited capacity to change.

Reduce wasted food

- Reduce pre-consumer food waste—Provide incentives for farmers to donate surplus food to emergency food providers. The West Virginia Food & Farm Coalition was instrumental in advocating for a recently passed West Virginia law to do just that. Across the Atlantic, France, Italy and Spain have also incentivized (or required) supermarkets to donate surplus food (though others propose landfill taxes as a more effective strategy).

- Change institutional practices—Encourage government institutions to purchase and serve “unattractive” produce, less popular cuts of meat, etc. Similar to how the USDA and EPA champion national businesses and organizations with food waste reduction commitments, local and state food policy councils can offer awards or recognition to local restaurants and businesses that have innovative food waste reduction strategies. Check out ReFED’s food waste innovator database for ideas.

- Composting—Require separate food waste bins in municipal waste collection for households and businesses. A number of cities already collect residential food waste (including Portland, OR; San Francisco, CA; Seattle, WA; and increasingly New York, NY) or offer households incentives for home composting (Austin, TX). Massachusetts requires businesses and institutions to compost food waste instead of sending to landfills or incinerators, and Vermont is phasing in similar legislation that will also apply to households.

Moderate environmental impacts of current agricultural system

- Farmer support—Advocate for funding for local Extension offices and state agricultural departments to train local farmers in transitioning to more GHG-efficient production systems (e.g., no-till or low-till farming, livestock feed changes to reduce methane emissions, carbon sequestration through re-forestation/perennial planting/pasture-grazing animals). The San Diego (CA) Food System Alliance secured a $25,000 grant from The San Diego Foundation’s Climate Initiative to develop a plan to test carbon farming practices on a local farm. The hope is that the results of the pilot will provide evidence of the feasibility and impact of carbon farming so that it will be included in the County’s climate action plan (Cities and counties in California are required by law to create climate action plans that align with California statewide goals of reducing GHG emissions by 15% by 2020.).

- Support the regionalization and diversification of supply chains—Invest in education, research, and policies that rebuild the food supply chain at the regional level, which can maintain efficiencies of scale (compared to “local”), while also reducing transportation distances and the vulnerability to food shortages that comes with dependence on single sources. Food Solutions New England has organized stakeholders from six states to advance sustainable farming and fishing within their regional foodshed.

To reduce the harmful impacts that climate change will have on residents and other non-humans (adaptation):

- Support farmers— Advocate for funding for local Extension offices and state agricultural departments to research and increase awareness of the impacts that climate change is projected to have on agriculture in the region (e.g., water scarcity, crop failure due to changing weather patterns, spread of new pathogens and pests, increased potential for food-borne illness). Partner with these organizations to begin developing plans to address potential changes, such as by planting new crop varieties and diversifying farm outputs in case of increased crop failures.

- Preserve farmland—Pass county or state level policies (e.g., conservation easements, land trusts) to protect regional farmland from encroaching development. This will protect the capacity of regions to produce food in the future, again reducing the vulnerability of food shortages that come with dependence on centralized supply chains. The Missoula (MT) Community Food and Agriculture Coalition has garnered a groundswell of public support for local agricultural land conservation policy over the past nine years. The Connecticut Food Policy Council also played an integral role in convening environmental and agricultural interests to form the Working Lands Alliance, which has been the prominent statewide voice for farmland preservation efforts since 1999.

- Promote urban agriculture and green space—Many food policy councils have played important roles in introducing and advancing policies and programs to encourage the burgeoning urban agriculture movement within their jurisdictions. While growing more food in cities has limited, if any, potential to reduce GHG emissions (or supply significant amounts of residents’ dietary needs) in the food system, it can help cities adapt to the impacts of climate change through moderating the urban heat island effect, diversifying supply chains (which may supply food in times of crisis), reducing storm-water runoff, and protecting crop varieties that may be important. Atlanta (GA), for example, has promoted urban agriculture and green space through a combination of city ordinances, including efforts led by the Atlanta Local Food Initiative. The City has both an Urban Agriculture Zoning Ordinance and a Special Administrative Permit for Urban Gardens to expand the areas where food can be grown in city limits. The Atlanta Local Food Initiative also supports orchards within city limits by donating fruit trees, vines, and berries to community gardens and schools.

- Encourage municipal and state governments to create food resilience plans: Environmental, political, and humanitarian emergencies can threaten food supplies. Food policy councils can advocate for funding for local and state governments to develop plans to reduce the impact of such emergencies. The Baltimore (MD) Food Policy Initiative and partners have developed a Food System Resilience Advisory Report, which recommends strategies to connect small food retailers and food pantries with preparedness training and incentivize purchase of backup equipment like generators. Stay tuned for an upcoming blog post by Erin Biehl with more specific recommendations on resilience planning for cities, based on Baltimore’s experience.

It’s important to recognize that food policy councils work on many food system issues at once (often with mostly volunteer labor) and that climate action often seems beyond their capacity and scope. It may also be beyond the interest of the community served by the food policy council. For instance, the results of a community survey led by the Asheville-Buncombe (NC) Food Policy Council showed that disaster mitigation and resilience planning ranked low on a list of priorities identified by community members. However, the City of Asheville is currently undertaking an emergency action planning process, which provides an opportunity for the Council to talk about the relationship between food and climate change. Councils may find their time is best spent in partnership with or supporting the leadership of other groups, such as government agencies and organizations that are tasked with addressing climate change and resilience issues. Partnering with others already working in similar areas may help share the workload and also help make such actions more feasible and effective.

Special thanks to Anne Palmer, Karen Bassarab, Erin Biehl, Becky Ramsing, and Kate Clancy for feedback and suggestions on this blog post. An additional thanks to Lily Sussman for early research assistance.

Image: UNEP 2016

[i] On average, transportation contributes only 11% of a food’s GHG emissions compared to the 83% of emissions attributed to agricultural production. One exception is air-freighted fish and produce, as this transportation process can more than double the GHG footprint of these items.