The need for a more efficient transportation system is apparent as we continue our collective journey down the path of The Long Emergency (James Howard Kunstler), The Long Descent (John Michael Greer), or whichever term you’d prefer to use. What I’ve noticed is that while discussions among resilience and sustainability advocates about what to do to adapt our transportation system to this reality are generally on the mark, there is a gap that needs to be addressed. Here at Resilience.org there have been articles about how we need to build high speed rail or this one that is more focused on conventional rail. Both focus on the need to move people. More recently, there have been articles about the need to reduce our dependence upon truck transportation for freight and the need for more sustainable food transportation which focuses on the need for electric trucks.

What if I told you that a good, conventional passenger rail system can move people, food, mail, and certain types of freight and that America’s passenger rail system once did all of these things? And what if I told you that in addition to all of these benefits, it fostered community and offered conveniences to the lives of Americans that we don’t have today? Well it did, and that’s the story I intend to tell you.

The Passenger Rail System That Was

There was a time when America’s passenger rail system was the envy of the world. Dozens of railroads offered multiple frequencies and classes of trains that served every major city and most small cities and towns. There were the fast express trains that served major endpoints, limiteds (meaning limited stops) that served larger cities and towns, and locals that served virtually every community along the line. There were dozens of famous named luxury trains like the New York Central Railway’s 20th Century Limited, the Seaboard Air Line’s Orange Blossom Special, and the Southern Pacific’s Coast Starlight. There were many more nameless trains offering local, regional and long distance services with coach class and a variety of sleeping accommodations from lie-flat seats to berths to compartments to drawing rooms.

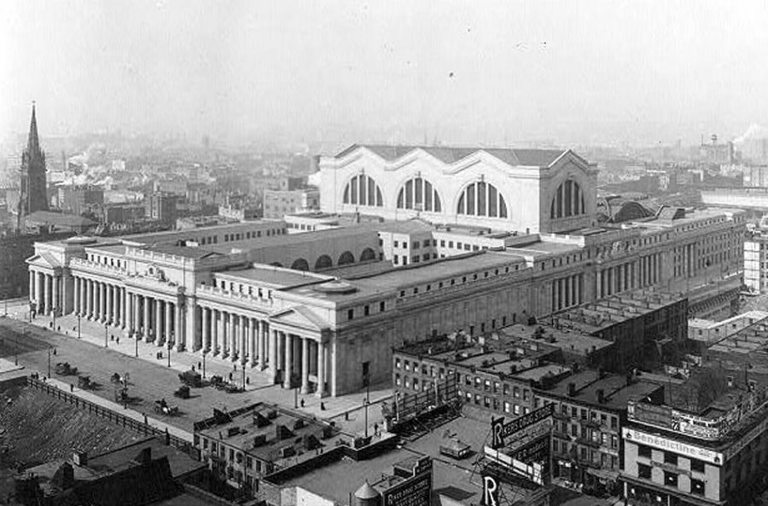

The railroads also built stations that were deliberately designed to be monuments to the cities they served and make passengers feel important. Grand station buildings existed in every major city in America, but even in small cities, station buildings embodied this idea. Many of them, however; including Penn Station in New York City have been thoughtlessly demolished. Architectural historian Vincent Scully said about Penn Station’s demolition: “One entered the city like a God. One scuttles in now like a rat”.

The original Penn Station after its grand opening in 1911. It was demolished in the 1960s for the construction of Madison Square Garden. The train station is now entirely underground. Source: Wikipedia, Public Domain

If you have ever driven through a small city or town and seen a “Railroad” or “Depot” Street, whether or not the tracks are still there, it’s because at one time there was a passenger station in that town. What’s interesting is that you’ll find this in more towns than you’d expect, because at its peak, the United States had 10,000 railroad stations. Amtrak serves a little over 500 today with its trains and connecting buses. If more than one railroad passed through, even a small city might have two or more stations. In many of these places the station buildings are still there and either put to other uses or rotting away. “Railroad” or “Depot” Streets are so common because railroads were once common enough and important enough in American life to identify the location of the local station with a street name.

We all know now that today America’s passenger rail system is a pathetic skeleton of its former self. James Howard Kunstler has said repeatedly that America has “a passenger rail system that Bulgarians would be ashamed of” and he is right. Our stubborn refusal as a nation to invest in passenger rail will make The Long Emergency that much more difficult to manage.

As we move further in time away from America’s “Golden Age of Rail” that existed during the first half of the 20th Century, the nation’s institutional memory about just how much we’ve lost is fading, and what we lost was a lot more than just a way to move people. We also lost a system of incredibly efficient, multi-purpose mobility machines that moved mail, parcels, and express freight very efficiently. In fact, without all the mail and express freight those passenger trains would have never been profitable for the railroads, just like airlines today would never be profitable if it wasn’t for (subsidies aside) all of the express freight and mail shipped below the passenger compartment.

Today, it takes a more energy intensive combination of automobiles, trucks and airplanes to do what a single passenger train was able to do in 1950. Furthermore, we lost a level of convenience in our lives that is in some ways unmatched today, and we lost a sense of community that our passenger rail system helped build and hold together.

I realize that not many people write letters anymore, but think about how much it costs today to mail a letter overnight say, between the cities of Chicago and New York. As of March 2017, the overnight rate starts at $23.75 if you use a US Postal Service flat rate envelope. In 1950, it was possible to drop a letter in a mail slot in Chicago’s LaSalle Street Station and have it delivered in New York City by noon the next day—for the cost of a first class postage stamp (47 cents today). That’s because passenger trains offered an efficient way to move mail.

Mail was moved either in dedicated mail cars on the front or rear of the train, or it was picked up and dropped off on the fly from Railway Post Office (RPO) cars all along the line and sorted enroute. Under this system, even same-day delivery was sometimes possible along a single railroad line.

Demontration at the Illinios Railway Museum of a mail hook on an RPO car pulling a mail bag onto a Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad Train. Photo by H. Michael Miley, located on Wikipedia. Creative Commons 2.0 Generic License.

A working RPO on the Chicago and Northwestern Railway in 1965 from Wikipedia. Public Domain.

Nowadays the US Postal Service uses a combination of regional sorting centers and trucks. For example, if you live in Ashtabula, Ohio (located in the far northeast corner of the state) and want to send a birthday card to someone in Jefferson, Ohio, a small city approximately 10 miles south of Ashtabula, it will be trucked approximately 60 miles to Cleveland to be sorted then trucked 60 miles back to Jefferson. These two cites used to be connected by a railroad line and both used to have passenger service. Now that birthday card moves 120 miles instead of 10.

Beginning in the 1950s, the US Post Office moved increasing amounts of first class mail from trains to airplanes and trucks. A lot was still moved on passenger trains in the 1960s, but in 1967 the Postmaster General, who was a former executive with the aviation industry, moved all remaining first class mail from the trains to airplanes. Though passenger service was already declining because of heavy government subsidies to highways and aviation, this was the final nail in the coffin, so to speak, and the trains began to hemorrhage money. It took an act of Congress to save what little remained of America’s passenger rail system which was taken over by Amtrak on May 1, 1971.

Just to be clear, I’m not advocating the resurrection of RPO cars exactly as they functioned in the past, but passenger trains could easily be used to ship mail in some fashion today.

Railway Express Agency

Railway Express sign, Northern Pacific Railway Depot, Washington St. & Railroad Ave, Ritzville, Washington, U.S. By Joe Mabel, Wikipedia, Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0 License.

Before FedEx, UPS, and DHL, there was the Railway Express Agency (REA), and with their fleet of green trucks and railcars, they provided a more efficient and customer-focused service then parcel companies do today. The REA was created in 1917 when the US government temporarily nationalized the railroads during World War I and consolidated seven different express companies into one. By 1929, it was fully privatized and jointly owned by 86 railroads. The REA was a common-carrier shipper, meaning they had to take just about anything that people brought to them– whether it was a crate of chicks, consumer goods from the once famous Sears catalog, parcels, household items if you were moving, refrigerated cars of produce and food, and virtually any high-value express freight that required the the speed and regular schedules passenger trains offered. Furthermore, they did it with a level of customer service that is unparalled today. Klink Garret, former REA employee and author of Ten Turtles to Tucumcari, a memoir about his career with the REA, said that when he was first hired, his boss told him if someone wants to ship ten turtles to Tucumcari, your response should be: “Are they painteds or snappers?”, meaning you find a way to serve the customer no matter what. Imagine getting that level of service out of today’s parcel companies.

Railway Express Agency employee Dorothy Bell sorting packages, June 1943, New Britain, CT, By OWI – Library of Congress, Public Domain

Railway Express Agency employee Dorothy Bell sorting packages, June 1943, New Britain, CT, By OWI – Library of Congress, Public Domain

The REA would also offer door-to-door shipment of people’s luggage, which is a convenience we no longer have today. Think of it: you could have your luggage picked up at your house and it would be waiting for you wherever it was you were going, be it a hotel, vacation home, or your grandmother’s house, and the most you would have to take with you was an overnight bag. This is a foreign concept today. Several years ago, when my son was a toddler, my family and I took a train trip to the Southwest. There was a luggage item that we didn’t want to have to fuss with, so we had it shipped via a parcel company to our chosen lodgings. Not only was it quite expensive, but the concept of receiving and holding on to a piece of luggage for a day or two until we arrived completely puzzled the employees there. They allowed us to do it but made it sound like we were inconveniencing them.

Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railway, REA Baggage and Express Car 2660; By SMU Central University Libraries, Source: Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railway, REA Baggage and Express Car 2660; By SMU Central University Libraries, Source: Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

The variety of things the REA would ship for people was greater than you might imagine. Going to a cottage on a lake and want your canoe? Going home from college and want your trunk of stuff shipped from your dormitory? They would ship it all right to your doorstep, but as the passenger rail network began to shrink so did the fortunes of the Railway Express Agency. Even though the company had diversified over the years and was using aviation and highways in addition to rail, the company declared bankruptcy in 1974 and closed for good.

The former Erie Railroad station in Kent, Ohio. Under the blue bridge in the far background is where a farmer’s market is held during the summer and fall. If this were still an operating railroad station, a farmer could potentially ship her/his food to the farmer’s market using the train and an REA-like service. Note the aesthetic and dignified architecture of the station building. Photo by author.

The former Erie Railroad station in Kent, Ohio. Under the blue bridge in the far background is where a farmer’s market is held during the summer and fall. If this were still an operating railroad station, a farmer could potentially ship her/his food to the farmer’s market using the train and an REA-like service. Note the aesthetic and dignified architecture of the station building. Photo by author.

How Passenger Trains Built Community

I would argue that America’s automobile culture has been one of the biggest contributors to the loss of community in our country. It’s not the only reason by any means, but it is a significant one. Being in an automobile places us in an isolated bubble, separated from other people. This removes the checks and balances on our behavior that being in the public realm normally encourages when you have to look people in the eye and speak to them. This makes it easier for people to drive aggressively, commit road rage, and develop a mindset that all the other drivers on the road are the ones ruining their day. As the book Natural Capitalism put it:

The problem of excessive automobility is pervasive. Congestion is smothering mobility, and mobility is corroding community…Street life and the public realm are sacrificed as we meet our neighbors only through windshields. As architect Andres Duany puts it, this stratification “reduces social interactions to aggressive competition for square feet of asphalt.”

Back when the passenger train was the dominant mode of overland transportation, we had to be in each other’s company much more often. If you’ve ever been on one of Amtrak’s long distance trains, you know that people tend to behave differently on them. There can be a few who are exceptions of course, but for the most part, people are more friendly and relaxed on the train. There are nice, comfortable seats with plenty of legroom and time to just sit and watch the world go by. Passengers can get up and walk from car to car. These things reduce stress which makes social interaction easier and more pleasant. Community seating in the dining and lounge cars further encourages social interaction, and when your behavior is on display for a many hours or days long trip, you tend to behave differently than in an airport or in a car on a crowded freeway.

That sense of community; however, went deeper than just being on a train with other people. Train stations were an important center of community life and the smaller the city, the stronger that connection was. Virtually everyone had to come to the station for something—whether they were traveling, meeting a friend or family member, or stopping by to ship or pick up a package. The local REA agent was one of their neighbors. Going to the local station meant crossing paths with other people in your community. It was another way that people would see and interact with their neighbors and spend time in the public eye.

For those who may doubt how much a passenger rail system and the local train station can help build and encourage community, look no further than the trackside canteens that operated during World War II, the Korean War, and, in a few places, even the early years of the Vietnam War. These canteens are described in detail in Scott Trostel’s 2008 book: Angels at the Station. Back then, soldiers were shipped to and from their overseas assignments on “troop trains” operated by the railroads under contract with the US military, and soldiers on leave would use the civilian trains.

Trackside canteens were staffed by volunteers and funded by donations. They offered food, beverages, and other items to soldiers such as sandwiches, baked goods and hot coffee as well as newspapers, magazines, and sundries—all free of charge. The canteens boosted morale, and for servicemen who were on leave for a final visit home before being shipped off for good, they provided much needed nourishment. Soldiers on leave did not receive any travel expenses, so they were on their own for travel and food, and they often didn’t have enough money to pay for much beyond their train ticket. The canteens were for them a godsend.

American Women’s Voluntary Service Canteen, Lima, Ohio 1942. Source: Allen County Museum & Historical Society. Used with permission.

Canteen Volunteers serving a US troop train passing through Lima, Ohio during WWII. Source: Allen County Museum & Historical Society, Lima, Ohio. Used with permission.

Canteen Volunteers serving a US troop train passing through Lima, Ohio during WWII. Source: Allen County Museum & Historical Society, Lima, Ohio. Used with permission.

Today, our servicemen travel overseas and come home out of sight and out of mind, and even if there were a major war effort of the likes of World War II today, fewer people feel the obligations to their communities than in the past. Furthermore, it is really only the passenger train that lends itself to an endeavor like the canteens because train stations tend to be easily accessible and located in downtown areas.

Conventional Rail is More Important than High-Speed Rail

With the converging crises we have with peak oil, climate change, and economic decline, it should be a no-brainer to re-build our conventional passenger rail system because not only can conventional passenger trains run on a variety of fuels, they can operate on tracks shared with freight trains, and they can provide the multi-purpose parcel, mail, and express freight services—all in one vehicle. Today, it takes a number of trucking movements to do what a single passenger train was able to do 60 years ago.

High speed trains, which in the US means speeds in excess of 125 mph, are useful for moving passengers in densely-traveled corridors, but they cannot perform the multi-purpose function that conventional trains can. High speed trains must be light weight, and they require infrastructure that is completely grade-separated from roads and conventional rail lines. That’s not to say that we shouldn’t consider high speed trains in some areas, but high speed trains were designed primarily to compete with air transportation which we can expect to decline as The Long Emergency progresses. Furthermore, high speed rail is most successful when it is built where there is already an established and well-used conventional system—it’s meant to augment a conventional system, not replace it.

In our discussions about building a more sustainable transportation system we cannot forget the multi-purpose role a convenentional passenger rail system can play—and must play again.

References

Carlson, Mark, retired US Postal Service employee, personal communication, March 30, 2017.

Garret, Klink, Ten Turtles to Tucumcari: A Personal History of the Railway Express Agency, 2003, University of New Mexico Press, 186 pp.

Goddard, Stephen, Getting There: The Epic Stuggle Between Road and Rail in the American Century, 1994, Basic Books, 351 pp.

Hawken, Paul, Lovins, Amory, and Lovins, L. Hunter, Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution, Little, Brown and Company, 1999, 396 pp.

Hutchison, William H., retired US Postal Service employee, personal communication, March 30, 2017.

Jacobsen, Shaun, Transitized, “How I Moved Across Country Using Amtrak.” http://transitized.com/2014/08/20/moved-across-country-amtrak/ August 20, 2014.

Pennsylvania Station (New York City), Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennsylvania_Station_(New_York_City), Updated March 25, 2017.

Railway Express Agency, Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc Updated March 24, 2017 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Railway_post_office

Railway Post Office, Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc, Updated March 16, 2017 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Railway_Express_Agency

Stilgoe, John, Train Time: Railroads And The Imminent Reshaping Of The United States Landscape, 2007, University of Virginia Press, 304 pp.

Trostel, Scott, Angels at The Station, 2008, Cam-Tech Publishing, 262 pp.