NOTE: Images in this archived article have been removed.

Successive governments have pursued an agenda of market competition, outsourcing and privatisation within public services. Their aim? Innovation – the kind that clunky, state run services apparently cannot deliver. For our politicians, the market has become synonymous with better services at lower costs.

But is this actually the case? Evidence is surprisingly

hard to come by. Decades of restructuring and reform have gone by without much effort to find out.

What limited evidence there is gives cause for concern. A recent survey of 140 local authorities shows the majority are beginning to take services back in-house, citing concerns about rising costs and decreasing quality.

Pay and conditions for services staff have plummeted and transparency has given way to commercial confidentiality. Power has been concentrated in the hands of a few supremely

wealthy private providers, now dogged by a series of high-profile scandals and widespread

public mistrust.

What, really, did we expect? Attempting to force innovation by pitting providers against each other naturally breeds fragmentation and opposition between stakeholders – which in turn discourages the partnerships and holistic thinking necessary for joined-up and preventative services. Efficiencies are sought by squeezing workers’ time, undermining the potential for caring services; and by cutting wages, causing

diminishing morale, retention rates and productivity. New targets and auditing regimes have been introduced to regulate a diversity of providers, side-lining local priorities and knowledge in the process. Shareholder value has been allowed to trump social value, eroding collective responsibility and

solidarity.

It’s clear the market is failing to deliver on its promises. But another way is possible.

A new report from the New Economics Foundation (NEF) [pdf] explores how, by shifting power away from private sector providers towards citizens and frontline staff, we can unlock a very different form of innovation. After all, these are the people who are most likely to care about ensuring high quality, inclusive services. When you work in or use services day in day out, you get a real sense of what’s working and what needs to change.

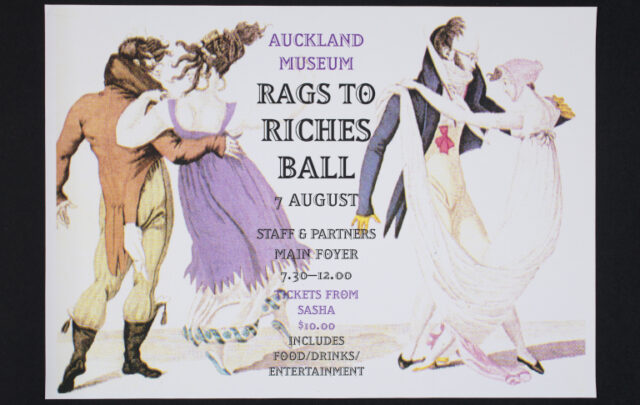

Public services graphic via nef.

Some public agencies, across the UK and beyond, are already enjoying the benefits of non-market innovation.

Co-production – services designed and delivered through an equal partnership between professionals and service users – is catching on. Islington council now co-produces the commissioning of its youth services: young people helped develop a new quality assurance framework and have been trained to lead site visits to assess how services meet their needs and expectations.

Co-production is not about devaluing or replacing professional expertise or shifting responsibility away from the state and public servants. Rather, it is about protecting and building on existing professional skills and enriching this with the resources and perspectives offered by citizens.

The success stories do not end at co-production. Following

impressive results in Porto Alegre, Brazil, more UK public agencies are giving citizens direct control over public spending decisions through participatory budgeting. Councils such as

Newcastle have demonstrated the benefits of less hierarchical working cultures that afford frontline staff more autonomy and trust. And Co-operative Trust Schools show how the public sector can work in collaborative partnership with other not-for-profit organisations.

However, the failure of David Cameron’s Big Society shows that increased local control is no good when people

lack the resources necessary to participate and benefit. Alongside devolution, we need redistribution. We need an end to austerity policies, which, as well as damaging public services, are

undermining the chances of a sustainable economic recovery.

Legislation advocated by campaign group

We Own It would be a healthy start for getting to a different model for public services, grounded in public participation.