At the entry of the scenic Black Forest (Schwarzwald) in the upper Rhine valley, is Freiburg, the sunniest and warmest city of Germany. It was established in the early twelfth century and the city is known for its medieval university and progressive environmental practices. It is situated in the heart of a region that has a diverse agricultural production and small-scale farming. Lately, the growth of large-scale, monoculture farms has led to the decline of family and small-scale agriculture, particularly through farm consolidation. Half of the farms in the state of Baden-Württemberg, where Freiburg is located have closed down in the last 20 years. For those who want to buy a farm it is very hard to secure working capital and land. This is also reflected in the food situation. Despite its good climate and diverse traditions, it is estimated that today only 5% of the food in Freiburg is sourced in the region.

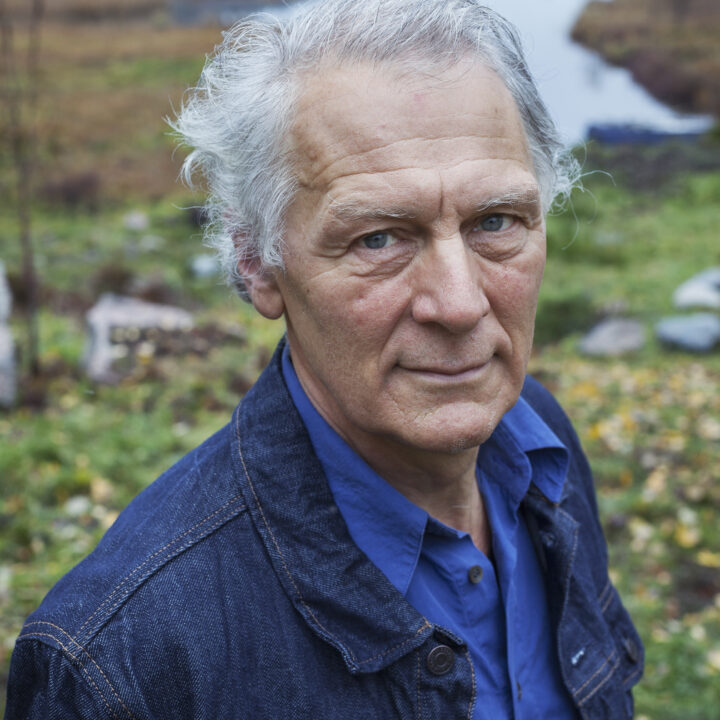

Christian Hiss grew up on one of Germany’s first organic farms, started by his parents in 1953 in Eichstetten, not far from Freiburg. His father had been a prisoner of war in England and came in contact with organic agriculture during captivity. He brought these ideas home to Germany. Christian started a vegetable farm as an own enterprise, at the age of 21, in the village in partnership with his wife and in the 1990s he started seed breeding. Christian felt that it was ”increasingly difficult to include organic values in the enterprise”. For all the needed inputs, seeds, land, operating capital and knowledge the market logic applied and even in the organic sector his colleagues were increasingly discussing things from the perspective of if it was profitable or not. Furthermore, Christian encountered all the problems of agriculture nowadays like lack of access to capital, unclear farm succession, poor valuation of socio-ecologic services etc. When he asked for a loan from the bank to build a new cowshed and the bank turned him down it was time to act. “If it was so difficult for me to raise capital even though I had inherited the farm, how difficult will it not be for a new farmer?”

There was a need to find a new form to do business, and he formed the Regionalwert[1] AG (RWAG) in 2006. It is a model for what Christian calls Community Connected Agriculture, as people support farms and food business not only in their role as consumers. Farmers should not see society as consumers and society should not see farmers only as producers. It is a question of relationship and dialogue, and “dialogue is about embeddedness” says Christian. The main point of intervention of RWAG is to supply organic farms and other actors in the whole food chain with capital. However, access to capital is not the only intervention; the RWAG also helps the organizations they support with market integration and they have established a regional brand.

|

| Happy cow at Breitenweger Hof |

”It is easier to sell the eggs through the other RWAG network partners, for example the Frischekiste, the box scheme” says Philipp Goetjes at the Breitenweger Hof in Eichstetten, where he has an organic dairy and egg production together with his wife Katarina. The cooperation extend beyond market; Jannis Zentler and a colleague at Querbeet Garden (the farm originally started by Christian), another RWAG partner, grow vegetables on 13 hectares, but they also have 7 hectares of clover grass, which is fed to Philipp and Katarina’s cows in exchange for manure. Jannis tells me about the bio-dynamic association which has been working together with the farm ever since it was established long time ago, “they know the place better than we do, and they want to have old varieties and seasonal food”. Those consumers are very different from those that just want to buy organic foods.

Today 500 persons in Freiburg have invested in the RWAG. All sorts of people are shareholders, the biggest investor has 7% of the capital and the total capital available was more than 2.3 million Euro in 2013. If their business plans are viable, the RWAG offers the entrepreneurs various forms of investments in business expansion. Often RWAG provides capital for a fixed rate of interest of between 3-8% on repayment (for land, machines etc). Another approach is to buy land and farms and lease it to farmers at a reasonable rent. RWAG can also be a partner or a shareholders, e.g. in the shop Regionalwert Biomarkt Waage in Emmendingen where it has 40% of the shares. They support sixteen operations, including a winery, 2 vegetable farms, a box scheme, a catering company and a wholesaler, a cheese farm, 2 shops, a mixed farm, a dried fruit operation and an accountant (also part of the food chain!).

RWAG works with a set of 64 sustainability indicators covering aspects such as employment structure and wages, biodiversity and resource consumption, value creation for the region and dialogue within the value chain. These are reported annually for all the enterprises and then compiled in an annual report, for example the proportion renewable electricity, used by the companies increased from 62% in 2009 to 98% in 2012, while the proportion renewable energy for fuel is still zero. So far there are no incentives for the enterprises to actually improve apart from the honor of doing so. Christian wants to see a system where enterprises are rewarded for this and equally that those that destroy the environment have to pay for it, but that will rarely materialize in the voluntary market. Barbara, the manager of the shop I visit also notes that “some consumers are interested in the regional, but most are more interested in diversity.”

The post is part of the process of writing my upcoming book Global Eating Disorder – the cost of cheap food. I am looking at different models to change our food system, in terms of production and consumption, but in particular in creating new relationships in the food system, preferably relationships that transcends the consumer-producer dichotomy.

[1] Regional Value Ltd