I have just returned from Spain, where we had to go at short notice to give a farewell kiss to our stranded asset. Yes, our farmhouse, which had been the focus of all my dreams and efforts a few years back, was finally released from legal limbo land and the keys handed over to the happy new owners. We got back around half of what it cost us to buy it and do it up, but speaking with other people in the same situation we know that we are among the lucky ones.

What a strange place Spain is! This truly is a country where dreams go to die. To the casual visitor it looks like an earthly paradise. The entire region was bursting forth with a trillion wildflowers on our visit, the air was scented with jasmine and orange blossom and the boughs of the lemon trees still hung heavy with fruit. A bumper wet winter had left the Sierra Nevada mountains with a deep snow pack – meaning happy times for farmers in the year ahead – and the local people were just as courteous, graceful, witty and family-oriented as they ever were.

These were among the reasons why, almost ten years ago, we had chosen to go and live there. The ruined house on the side of a fertile hillside had been converted into a small organic farm. Our kids were happy to sit in the shade of an almond tree with a rock and bash open almonds while I either worked on the land or went into the office where I was running a small ecologically-conscious newspaper that I had set up. Life was good.

Or at least it would have been if we hadn’t taken out a loan to renovate the property. In time that loan became an unbearable burden and our dreams slowly dissolved before our eyes as we found ourselves forced to return to work in Copenhagen and live in a government subsidised flat for five whole years. That wasn’t part of the plan.

And we were the lucky ones. Those who steadfastly refused to leave are now stranded. Most foreigners have left the area. Those who stubbornly refuse to lower the asking price of their houses are hit the worst because they can’t cut their losses and move on. Instead they exist in a shadowy half-world of penury, trying desperately to earn a euro here or there and doing anything they can to keep the wolf – or in this case the bank – from the door. The last thing they need is escapees like me parachuting in and pointing out how lovely the smell of orange blossom is in the spring air.

Those with families to support face an unpleasant decision. With all work having dried up many are finding that the only way to feed their families is by doing illegal things. ‘Such as?’ I asked my friend, who is still desperately clinging on in a legal way. ‘All sorts,’ she replied. Dope grows remarkably well in Andalucia.

Only those who can draw money from the currently still-functioning pension systems of northern Europe are faring better. Yet even that may not be a shortcut to safety as healthcare costs are climbing just as they themselves go into decline. The Spanish have a word for foreigners like that. They call them ‘soloistas’ or some such word – loners. People without family who rely on their money from other countries, their healthcare from far away and a cheap and functional system of airlines to take them wherever they need to access these services. Many of them sit in their jerry-built concrete shells by their swimming pools, drink in hand, and convince themselves that they are still living the good life – even though sterling has depreciated, food costs have rocketed and all of their friends have either been evicted or hot-tailed it back to the country they had said they despised before things started to go wrong. Just one more glass of sangria and everything will be okay again …

Spain is a strange place. It has been in a state of free fall collapse for several centuries. One of my favourite writers, Jan Morris, described the country’s fortunes as (paraphrased) ‘like a rock bouncing, bouncing, bouncing down a steep mountain, its descent every now and again arrested by a small outcrop.’ Here was a country that had a vast empire that was able to liquidate – quite literally – the wealth of an entire continent and bring it home. Five centuries later it was one of the most backward regions of the western world and an embarrassment to the EU. And then the money began to pour in.

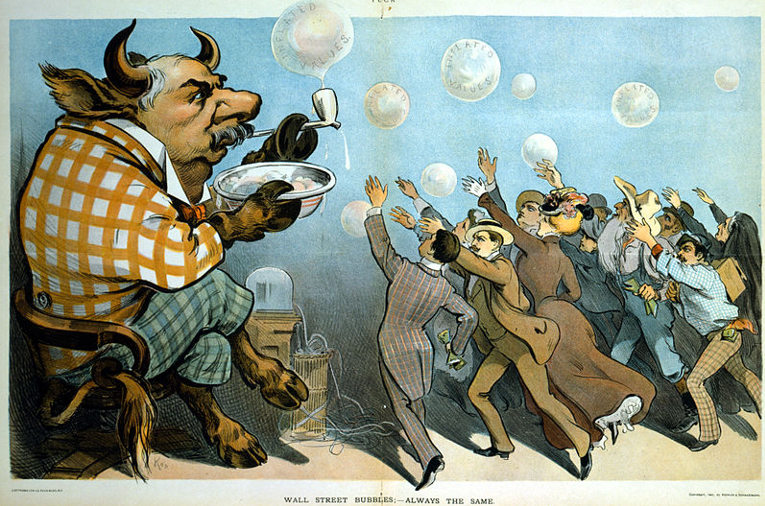

The money was used to modernise the country in a kind of Spanish Great Leap Forward. It was all about catching up. Building. Building roads and airports and millions and millions homes that nobody really wanted. You want ten thousand euros? – I’ll lend you fifty! Peasant farmers who owned dry and dusty parcels of land in Almeria – land that would have been literally worthless, almost a curse on the family – suddenly found they could borrow thousands from the bank to buy boring equipment, pumps, plastic greenhouses and fertiliser. All of a sudden they were rich on selling tomatoes and lettuces – and all kinds of other tasteless pseudo foods – to the moneyed northern Europeans, and could afford to employ migrant Africans in bonded slave-like conditions. New pickup trucks and a house by a golf course were suddenly the order of the day. It was a boom alright.

I’m happy that the place where we had chosen to live – La Alpujarra – was considered too backward even for this kind of boom. The roads were too bendy. The people were too simple. The land was too steep and the streets of the local town were full of the dirtiest and most bedraggled kind of New Agers. Sophisticated people from Granada would come and visit in their thousands every weekend and bring with them loud music, iPhones and shiny fast cars. The locals secretly called them ‘aliens’ and kept their mouths shut as they were serving them in their restaurants and guest houses. I’m happy to say I was never called an alien. At least, not to my face.

But what of these urban sophisticates now? They are among the ones we see on the news reports, living on food handouts and protesting against the government. With their safety blanket pulled out, unemployment rocketing (said to have reached 6 million last week) and the country’s political (and royal) classes being steadily exposed as crooks and liars, things suddenly don’t look so rosy. It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

Not so for my erstwhile neighbours who, by and large, are getting along just fine with their fields and their small houses and appropriately sized vehicles. Fertlizer and pesticides had always been too expensive, so not that many people had got into the habit of using much of them. These folks had always said things were terrible even at the best of times. The country people of Andalucia haven’t forgotten that the region is prone to famines, genocide and an unstable climate. Listen to some proper flamenco and ask yourself if this comes from a land of happy upbeat people.

Driving back down the coastal highway on the way back to the airport it was impossible not to notice how empty it was. This was a Saturday mid-morning and a few years ago one would have expected it to be moderately busy. Now, we saw a car only every few minutes. It felt like the whole road was ours – and this was the widely ballyhooed mega motorway that was supposed to be a ‘ring of tarmac’ encircling the whole of Spain. Sadly uncompleted, like a broken necklace.

In the news today I read that a Spanish woman dowsed herself in petrol and walked into a bank. The bank had taken her house and her savings and everything else she owned. ‘You have taken everything from me!’ were the words she shouted before igniting the fuel. Such stories are increasingly common.

What next for such a country? There is a growing chorus calling for the debt to be abandoned – for the country to walk away from its obligations to the monolithic banks and finance organisations and to set themselves free again. There is, if the truth be told, no other option. Whether it goes smoothly or is done with explosives is the only question worth asking. Alas, Spain’s history, if it can be used as a guide, doesn’t bode well. I’d love for someone to tell me that I’m wrong on this, but I’m not sure I’d believe them.

But I hope that in this case the past is going to prove to be no guide to the future. Spain held out for so long against the Anglo model of capitalism. Petty local corruption, ironically, kept development at bay and ensured the system as a whole remained resilient. It was only the surging tidal wave of EU reforms that swept away the small scale municipal corruption and replaced it with respectable-looking TBTF corruption.

Bounce, bounce down that mountain.