Part 1

As long as I have been engaged in food and agriculture, i.e. since the late 1970s, the dominating food and agriculture narrative is that we need to produce more in order to feed a growing population. While I do think there are reasons for concern about the future (I will write more on that soon), this view has two huge errors. The first one is that the problem today is certainly not that production is too low, on the contrary, overproduction is a major problem. The second one, is that the real problem of the agri-food system is how we produce, distribute and eat our food.

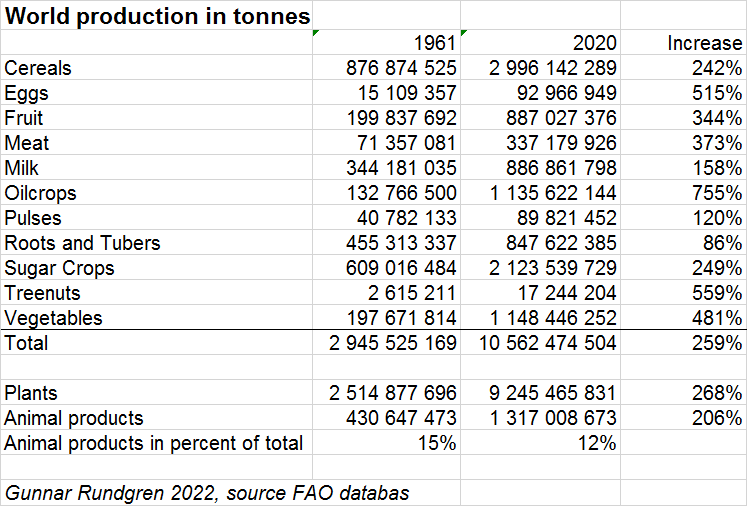

Without doubt, global agriculture output has increased tremendously over the last sixty years. Measured in tons world agriculture output of crops has increased 268% since 1961. The population increased 151%, i.e. the production per person increased 43%. Not all of this is eaten by people. Some of these crops are fed to livestock and livestock production has increased 206% in the same period. Notably, as the total consumption of food has increased the share of animal food per capita is more or less stable. Around ten percent of the crop output is used for biofuel and another smaller share is used for industry, printing ink, lubricants, paints etc.

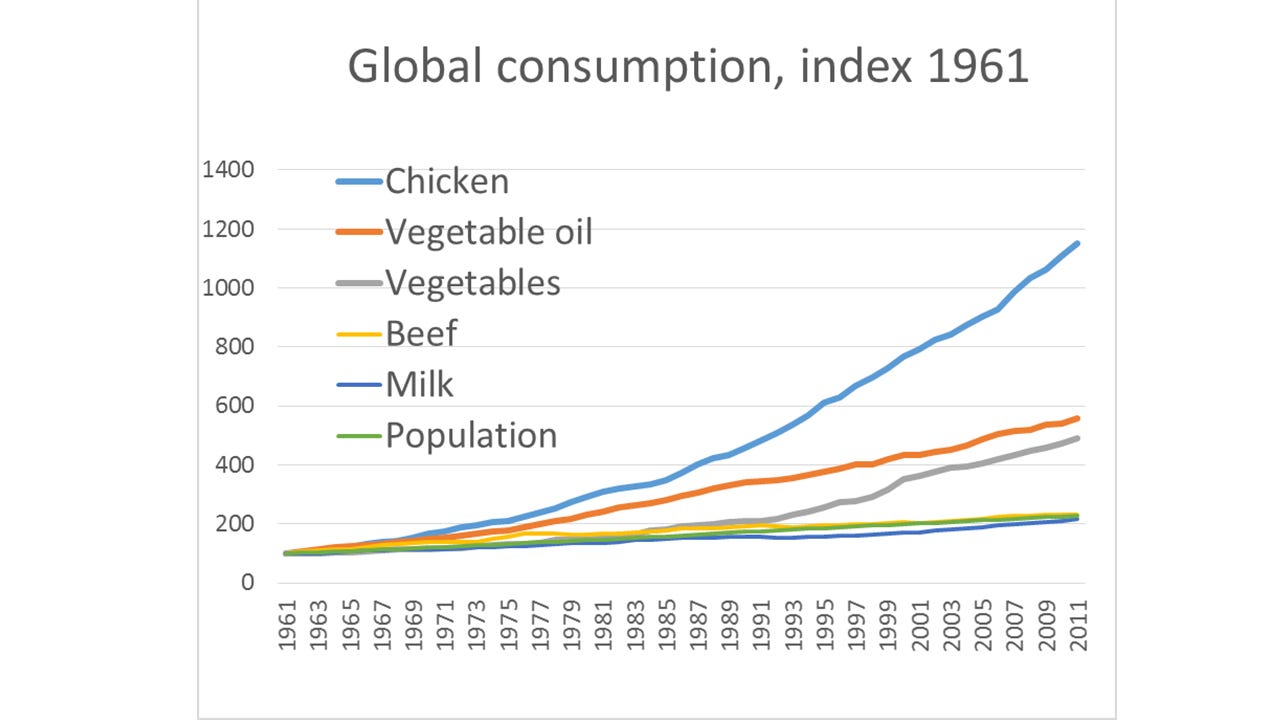

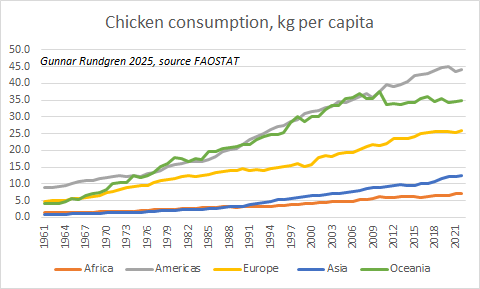

Pulses, roots and tubers have not kept pace with population. Oil crops have increased tremendously and nuts, vegetables and eggs have all increased more than 450%. Vegetable oil and chicken are the real rockets. Pork consumption has also doubled, almost totally attributable to China, where consumption went from to 2 kg per person in 1961 to 40 kg per person year 2022. The per capita consumption of beef, mutton and goat has been very stable and also milk. It is quite surprising that in the heated “meat” debate, articles are always illustrated with cows or a steak when the share of consumption is around 20% of all meat and that the main contribution of cattle to the food system is milk and not meat.

Source FAOSTAT

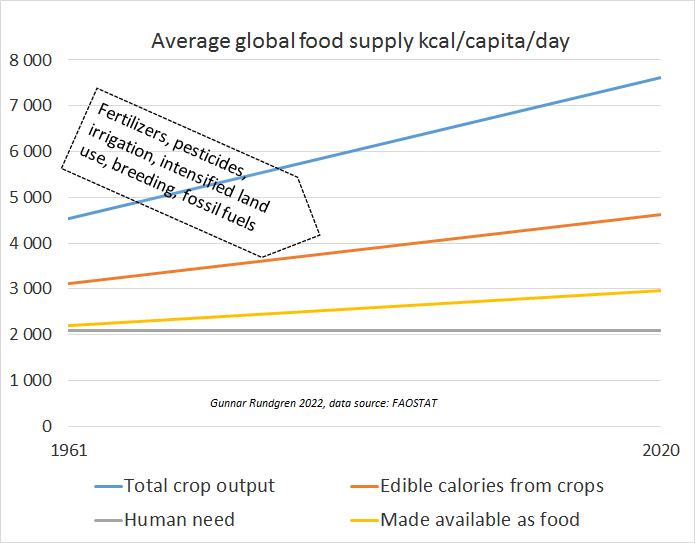

The gross crop output in energy per capita increased from 4,528 kcal 1961 to 7,619 kcal 2020, an increase of 68 percent. Almost 3,000 kcal per person per day is made available for consumers, who “need” in the range of 2,100 kcal per person per day. “Made available” should be understood as carried from the shop (if you are a consumer in a market society), brought into the household from your farm (if you are a self-sufficient homesteader, or the raw materials used in a restaurant (if you eat out). Of the difference, food waste and “metabolic food waste” (causing obesity) contribute roughly in a similar way (i.e. people waste >400 kcal per day and eat >400 kcal “too much” in average).

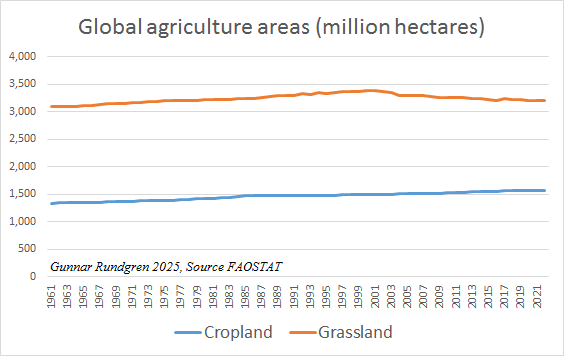

Cropland increase has played a minor role in the increased global output with an increase of just 17%. Global grassland area increased until around the year 2000 and then dropped, being just 4% higher than in 1961. The total masks quite a big regional redistribution where grassland areas in Europe, North America and Russia have shrunk while the area has increased in tropic and subtropic areas. Notably the statistics for grassland and even more how much of the grassland that is actively used is very uncertain, I discuss that more here.

The most remarkable development when it comes to output is in China, where output has increased almost 1000 percent. The output in China was accomplished with a small increase in cropland area and no increased use of labor but with a tremendous increase in the use of fertilizers. This was from a very low level, 2.3 million tons which went to 49.9 million tons. Chinese farmers now use 22% of all fertilizers in the world.

Irrigation and fertilizers have clearly been the two major drivers of yield increase. Irrigation in arid climates may mean a very high increase in productivity as well as multiple annual crops. In the Mekong delta farmers reportedly take three rice crops per year.

The increase in the use of fertilizers has slowed down a bit with a remarkable drop in the end of the 1980s, which has to do with the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellite states where fertilizers were heavily subsidized and used indiscriminately. As time goes on farmers have learnt to use fertilizers more efficiently, but there are limits to how much fertilizer use efficiency can increase. It has now reached a plateau in the countries that have used fertilizers for a long time. The total use of fertilizers has increased a lot more than the production has increased. Nitrogen fertilizer use increased 8.4 times between 1961 and 2022, phosphorus fertilizer 2.8 times and potash fertilizer 3.1 times.

The aggregate efficiency of nitrogen fertilizer measured in use of N per ton of crop output went down from 4 kg N per ton to 12 kg N per ton between 1961 and 2022. Nitrogen fertilizers are clearly one of the most harmful aspect of the global agriculture system. In addition to the direct or indirect environmental effect of nitrogen fertilizers, the use of nitrogen fertilizers have led to the abandonment of earlier more sustainable practices such as crop rotation, intercropping, and nutrient recycling. It is also the main driver for the decoupling of crop farming and livestock farming, which in turn led to livestock factories. Apart from being inhumane they are also a major source of pollution as there is far too much manure in a limited area of land.

There are many other negative aspects of “modern” industrial farming. The effect on climate, biodiversity and health are devastating. Taken together, the external costs of the agri-food system are estimated to be at least the same as the value of the total output. (I have expressed a lot of criticism against “true cost accounting”, which I believe is quite a dubious concept both from a pure scientific angle (very difficult and subjective to measure) and from a moral and political angle (including even more of nature into the market by the means of monetary valuation. Nevertheless the figures give you an idea of the magnitude).

Of course, one can’t separate the agriculture system from the food system and one can’t separate the agriculture and food systems from the economic system that sets their priorities. The enormous increase in the consumption of chicken and vegetable oil can’t be understood from a perspective of consumer preferences, but is explained by underlying economic conditions, which in turn are dependent on technology and politics.

All of it is, in turn, dependent on the biosphere and various ecosystems. That will be the topic of two following posts. In the final post I will sketch what the future agri-food system could look like.

Part 2

In my previous post, I gave a big picture view of the development of the agri-food system. While I mentioned fertilizers and irrigation as main drivers of increased production, I didn’t discuss the underlying drivers of the whole system and why our diets have changed in a certain way.

A brief history of the agriculture and food system

In my view the mega-trends of the last one and a half centuries have been 1) the use of fossil fuels in all stages of the food chain, 2) the increasing population and urbanization, 3) the commodification and globalization and, 4) the conversion of people to consumers.

The use of fossil fuels in the agri-food system changed the agriculture and food system in many different ways. An obvious case is the application of farm machinery such as tractors and combine harvesters.

Photo: Gunnar Rundgren

This freed up quite a lot of land that was used for feed for animal traction and, even more important, it “freed” a lot of people from agriculture work. The mechanization of agriculture is a prerequisite for urbanization and for development of an economy with an ever increasing division of labour. Another, perhaps not as evident, application of fossil fuels is the use of nitrogen fertilizers, a product made of nitrogen from the air with massive inputs of fossil fuels. This increased land productivity considerably and it also freed up land previously used for soil regeneration (fallow, green manure, biological nitrogen fixation). Before nitrogen fertilizers came into use, it was virtually impossible to run monoculture commodity crop production as the need for replenishment of nutrients required tighter nutrient cycles*. In this way, chemical fertilizers facilitated the geographic and ecological rift between plant production and livestock production as well as the production of humans (increased population) and their location (urbanization).

The urbanization, increasing population and the metabolic rift between production and consumption were facilitated and amplified by the introduction of fossil fuels for transportation. And the improved transportation system made virtually the whole world into one market. Even with (now increasingly popular!) tariffs, the cost of global transportation is so low that farmers all over the world compete with each other in a way that was not the case until steam ships started to cross the Atlantic in the later half of the 19th century. A bushel of wheat cost 60 cents in Chicago in 1870 and twice the amount in London. By the end of the century, transport costs, and thereby the price difference, had shrunk to 10 cents. Wheat exports from the United States to Europe went from 5 million bushels to close to 200 million bushels in the same time (Mazoyer, M. and L. Roudart 2006 A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis).

As you can see from this extremely condensed history of the agriculture system over 150 years, the four mega-trends are mutually supportive and have created a strong development complex, which is very hard to change. On a more existential level this development also turned people − citizens, friends and family − into the primary role of consumers. Obviously, this also changed how we eat and what we eat.

From Sunday chicken to KFC

Chicken is a good case in point. Global chicken consumption has increased from 2.9 kg per capita in 1961 to 17 kg in 2022. China has 17% of the global production, the US (16%) and Brazil (11%) (FAOSTAT). Global trade in poultry is estimated to USD 32.5bn. Approximately 13% of all chicken pass a border. Exports are dominated by Brazil (24%), the US (21%), Poland (8%), the Netherlands (7%) and Thailand (5%). The main importers are China, Japan, Mexico, UK, the Netherlands and Germany (FAOSTAT). But chicken is a lot more trade dependent than the figures of chicken trade reveal. Almost all chicken production is based on grain and soy of which in particular the soy is traded globally. For each kg of chicken meat, 0.6 kg of soy and 1.5 kg of corn is used, according to the RTSR Soy calculator. While the US and Brazil produce their own soy, China’s poultry (and their even larger pig production) is almost totally dependent on imported soy.

Traditionally, small numbers of chickens were raised on waste products or seeking their own feed in the farmer’s yard, the thicket or the manure heap – a very popular place for the animals. Chicken meat was relatively scarce and thus expensive in most cultures. Today chicken from broilers in the shape of nuggets, wings or strips are munched 24/7. There is hardly any other food that has increased its market share at such speed in such a short period. A trend analyst would explain that consumer choice is driving this, that consumers prefer white meat to red for health reasons, that chicken is low in fat, that chicken is an international food or that chicken is better for the climate than eating beef. Well, I’m no trend analyst and venture that the main explanation is that chicken has become much cheaper compared to other foodstuffs (see below). With the mega-drivers as a background, we can discern some factors which have played a major role in the transformation of the luxury that was “Sunday chicken” (listen to Dolly Parton!) into a very cheap food.

Earlier, most farms with animals also produced their own feed. With the large-scale introduction of chemical fertilisers after World War II and improvements in transportation technologies, farms no longer had to integrate animals and crops. With increasing mechanisation, crop farmers could produce much cheaper grain, and later on also soybeans – increasingly grown in monocultures. The grains were sold to specialised livestock farmers, including chicken producers. Chicken production, including the animal itself also changed to allow for industrial production (see box).

While there are efforts to intensify beef production, ruminants are not as efficient as chicken in converting the grain and soy surplus (pigs are in-between), and they are also more difficult to industrialize fully. This means that the relative price of beef and mutton compared to chicken has increased. Even in the US, where cattle breeding certainly is more industrialized than in many other places, the retail price of beef was already 2.5 times higher than chicken in the 1970s and 2017 it was over 4 times more expensive than chicken. In the last stage, the food industry, restaurants and stressed consumers appreciate the tender chicken meat that is easy to cook and season to almost any style as the industrial chicken has no own flavour.

How chicken became the most important meat

Chickens, just like humans, depend on sunlight to produce vitamin D. Therefore chickens would feed on worms and other insects in the yard and would be fed maize when they went back into the chicken house. Once farmers realised they could simply add vitamin D and other vitamins and medications to the chicken feed, they no longer had to let the chickens outdoors. Meanwhile, technology for automatic feeding had been invented. Now, the industrialisation of both broilers and laying hens could proceed apace. Mechanisation of the whole slaughtering process helped to reduce prices and increase volumes. In just over 50 years, the number of chickens produced in the United States increased 14-fold, while the number of farms having chickens dropped from 1.6 million to just 27,000.8 Half of all American broilers now come from farms producing more than 700,000 chicks per year.9 Big food industries came in and contracted producers for their brands and provided them with technologies and markets. At the beginning of this century three-quarters of global chicken production were in the hands of agribusiness companies.

The development of broiler production was paralleled by developments in the processing, marketing and consumer side. The birds themselves are torn into pieces and reconfigured in a multitude of products such as nuggets and strips. In 1930 the then 40-year-old KFC founder Harland Sanders (who never was a real Colonel) was operating a service station in Corbin, Kentucky, and it was there that he began cooking for hungry travellers who stopped in for gas. He called it ‘Sunday Dinner, Seven Days a Week’. Today, KFC, together with Pizza Hut and Taco Bell, is part of Yum! Brands, Inc., the world’s leading restaurant company with over 40,000 restaurants and 1.5 million people employed in more than 125 countries and territories.

Chicken breeding is extremely concentrated as a result of high research expenditure and the capital-intensive nature of the chicken business. By the late 2000s only three sizeable breeding groups remained for broilers: Cobb-Vantress, Aviagen and Groupe Grimaud. Two breeders control 94% of the supply of laying hens. All these developments have had profound impact on the main character of the story, Gallus gallus. In just half a century, the breeders created two different specialist chickens, each one incredibly efficient for its specific purpose. A typical laying hen of today needs 1.99 kg of feed to produce 1 kg of eggs, while a broiler hen will need 5.22 kg of feed for the same quantity. But the broiler chicken is far superior in converting feed to meat. To produce 1 kg of live weight the broiler needs only 1.7 kg of feed, while the chicken of a laying hen needs 3.8 kg. Unfortunately, both the broiler and the laying hen are less efficient than their common ancestor in being a chicken. Source: Global Eating Disorder, Gunnar Rundgren 2014

A blueprint for factory farming

The chicken industry provided a blueprint for the industrialisation of livestock. The capital-intensive model cuts out small farmers and pastoralists and is built on the use of bought-in inputs: feeds, medicines, technologies and breeding stock as well as external knowledge. The production model bears a close resemblance to assembly industries, and producers all over the world use the same breeds, feed and technology. What is particularly disturbing with the commodification of animal production is that it doesn’t take into account that animals are living, sentient beings. Through the commodification of animals, their welfare and their ability to exercise their natural behaviours have become externalities – side factors of production – just as the landscape has in plant production. The notion of landscape, place or culture in our foods has totally lost any meaning under these conditions, which is both a prerequisite for and a result of commodity farming.

The rise of supermarket chains, the fast food chains, factory farming, food waste, the conversion of landscapes into monocultures, food deserts, obesity, malnutrition, ultra-processed food, you name it –the four mega-drivers have a lot more explanatory power than the prevailing, and infantile, narrative of consumer preferences. In my view, the consumer is king narrative is an ideological construct of neo-liberalism giving capitalism and the market an air of democracy (voting with your wallet).

In the next post, I will go into the ecological perspective of the development of the agri-food system. In the final post I will sketch a vision for the future.

* Sometimes people speak about “closed” loops of recycling, but it is not really possible, all ecosystems have some degree of exchange with other ecosystems. Having said that, there is an underlying tendency to economize on nutrients as they often are in limited availability.