This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news.

Can a beloved forest bridge the gap between a fractured past and a hopeful future?

The following is the third installment of “Reimagining Rural Cartographies,” a new Barn Raiser series exploring innovative and nontraditional forms of mapping. It is guest-edited by Lydia Moran and funded by Arts Midwest’s Creative Media Cohort program.

Near the headwaters of the Mississippi River in Minnesota, more than 130,000 acres of the state forest—a dense swath of Northwoods—lie within the White Earth Reservation boundaries, home to the White Earth Band of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Yet the tribe does not have jurisdiction over that land. In total, the White Earth Nation, named for the layer of white clay in the reservation’s western half, owns a mere 10% of lands within their reservation; the rest are privately, state or county owned.

Jasmin Larson drives through the White Earth State Forest. (Maija Hecht)

In February, a bill introduced to the Minnesota legislature proposed transferring all state-owned lands within the White Earth State Forest to the White Earth Nation by 2029. The bill also mandated that White Earth Nation be first in line to purchase any tax-forfeited lands offered for sale within the state forest boundary.

Supporters of the bill, including White Earth tribal leadership and some non-Native residents, view the land transfer as a way to ensure the preservation of wildlife and areas within the forest that are sacred to Indigenous people. They also view it as an overdue reparation for the long, complex history of coercive land grabbing, forced displacement and schemes to defraud individuals from their land during the 19th and 20th centuries that placed the forest under state control in the first place.

The proposed land transfer met heavy resistance from residents of Clearwater, Becker and Mahnomen counties, which overlap with the forest. Many residents voiced concern that the tribe would restrict public access to the forest, which they argued could result in the loss of recreational activities.

While the bill stalled in committee hearings and died before the session ended, it illuminated logistical challenges and moral questions that will resurface if it is reintroduced next year. With the Land Back movement gaining momentum around the world, many communities are grappling with similar questions.

Having grown up just down the road from the White Earth State Forest, I was not surprised that the proposed land transfer was met with resistance. Despite living as neighbors, the rift between the predominantly white county residents and Native communities is palpable here, nurtured by a lack of cultural understanding and superficial history education in area schools. Yet many share a distinct love for the forest: its beloved fishing holes, miles of hiking trails and abundance of plants and wildlife, from black bears and beavers to mushrooms and edible herbs.

As I dug further into the White Earth State Forest and its fraught history, I began to wonder how these woods are used today. As spring turned to summer, I began exploring the forest with my camera to see who I would find. Some of those I came across were aware of the bill and the controversy that surrounded it, but many were not. Even more did not fall neatly into tribal or non-tribal affiliation—support or opposition. In many instances, the people I interviewed shied away from discussing their stance on the bill, but enthusiastically showed me the parts of the forest that mattered to them.

Clearing culverts, seeking morels, boiling sap

In March, I drive to the southernmost corner of the White Earth State Forest and happen upon a family from Mahnomen, a town of about 1,200 on the White Earth Reservation. Shane Lague and Melissa Anderson have stopped to clear a culvert near Giisaakoning, or Juggler Lake. Anderson’s girls play while the couple attempts to dislodge a small blockage from the culvert, “so the fish can get through.”

During spring snowmelt and rain, blocked culverts can cause flooding and wash away roads. On county lands, it is the responsibility of the land and forestry department to maintain culverts and stop flooding—in this case, locals help out.

The couple points out an eagle to the girls, who are distracted by my camera. When the eagle disappears into the pines, they start back towards the car. “Let’s go look for the next one.”

When asked how they felt about the proposed land transfer, the couple said they were unaware of the bill or its surrounding controversy.

A few weeks later, spring rains are followed by a few days of sun, and I accompany Jasmin Larson and daughter Willow to search for morel mushrooms. At each location we stop, Larson, an unenrolled White Earth descendant, scatters an offering of tobacco out of her window before opening the car door. “I always ask, and Gitchi always delivers. It just might not deliver what we’re asking for,” she says of the Great Spirit.

At one site, Willow points out a young turkey tail mushroom. When I point to a seemingly identical growth nearby, Willow frowns. “No,” she says. “This is more of a sage [green], and that’s more of a swamp.”

The season is early, and no morels offer themselves to us. Turning off the main road, Larson’s tires dig into the mud just north of Bass Lake. We’re stuck. The sun is setting fast and we are out of cell service. Moments later, we hear tires in the distance and Larson runs to flag down the truck. Faster than we’d gotten ourselves into the mess, we are being towed out of the mud by a pair of men who had been leeching nearby.

Before reaching the highway, we come across a man and his son next to a beaver pond and Larson pulls over. They’re friends of hers, also emerging from trails in the woods. Another woman in a car rolls down her window and calls out to Larson. She reveals two thimble-sized morels in her palm.

When it comes to the land transfer bill, Larson says her stance is firm. “It should be handed over [to the tribe],” adding that she expects to see more clarity from the tribal government on how the land will be taken care of.

“I don’t want to speak for everyone,” Larson says, “but I think Native people would want their resources accessible. We want the forest to stay the forest, and not be bulldozed down.”

On a foggy afternoon in early April, Kim Wannebo boils down his last batch of maple syrup in a small sugar shack on the border of the state forest. It all started after a relative left behind a large wood fire boiler. Wannebo was tired of the stove being rained on, so he built walls around it. And when the mud became a nuisance, he added a floor. Forty gallons of sap boil down to one gallon of syrup, so the process is a labor of love for Wannebo, who has tapped the same stand of trees for the past 14 years.

“It’s kind of like fishing. You’re not making any money out of it, but it’s a good excuse to get out into the woods,” he says.

Sugaring has always been “strictly for the fun of it,” but because the trees produce more sap than he can use, Wannebo started selling syrup and used the revenue to buy better equipment. Next to his sugaring shack, Wannebo operates a hub for small-scale makers where local honey and other crafts are sold without a commission. He plans to add a coffee cart to draw a broader community from the surrounding woods.

Wannebo says he doesn’t support the transfer. He worries that he’ll be unable to access land he currently enjoys if the tribe were to take over.

People often describe the White Earth State Forest as a place to get lost, where you’re unlikely to run into another human. But it seems that the opposite is also true; communities are built among those who tend and use the forest. For rural communities where there is a lack of public gathering spaces, the woods become an important resource. Because of this, the contention surrounding a land transfer stems far deeper than natural resource management. To locals who know the forest, the transfer is a disagreement on claims to a home.

Checkerboarding the forest

Part of the contention surrounding the land transfer proposal stems from how the White Earth State Forest came to be. The area’s history of clouded land titles, fraudulent land transfers and lack of accurate local history curriculum all contribute to poor understanding of how the land impacts present communities.

Fifty years after the United States began forcibly removing Indigenous children from their families to endure assimilation in residential schools across the U.S., the White Earth Reservation was established in 1867 in a treaty between President Andrew Johnson and the Chippewa of the Mississippi.

Twenty years later, the General Allotment Act divided or “checkerboarded” tribal land into parcels, pushing traditional communal structures of Indigenous tribes toward an individualized, agrarian society. Parcels were allotted to individuals based on household tribal status and blood quantum, a system created by the federal government in an attempt to measure a person’s “Native blood.”

In 1889 the Nelson Act decreed that all Anishinaabe people in the state of Minnesota, excluding those living on Red Lake Reservation, would be relocated to the White Earth Reservation. Some groups, such as the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, successfully fought back. Those who did move to White Earth fell victim to land theft as white settlers used force by threat of arrest, intoxication and deceit to steal land allotment patents. Tens of millions of dollars of sovereign land was stolen from Anishinaabe people, resulting in over 1,600 lawsuits. Once displaced, residents were sent to refugee camps within their own lands, where they suffered from trachoma and tuberculosis.

Each allotment and subsequent sale(s) are recorded in books like these ones in the Clearwater County Recorder’s office, where un-digitized allotment documents are still stored and open to the public.

One of the main goals of the Nelson Act was to open forest land to the timber industry. In addition to fraudulent sales, reservation lands were obtained through dubious tax forfeitures. If taxes were not being paid on an allotment of land, it was seized by the state to create the White Earth State Forest, according to research cited by state Sen. Mary Kunesh (D), an author of the land transfer bill, during a March 7 hearing.

“Timber meant money,” Kunesh said. “To a lot of people, just seeing a forest sitting there not being cut down and generating money is a waste.”

“The people were living their life there,” she continued. “Just because they didn’t build a house, farm or business, doesn’t mean the land was not in use.”

Access and trust

“I’ve been trying to learn more,” says Clearwater County Land Commissioner Bruce Cox, who testified in opposition to the land transfer bill in March. He gestures to a paperback book on his desk, The White Earth Tragedy by Melissa L. Meyer. “White men really screwed it up for everyone, there never should have been a reservation system,” he says. “The idea of ‘title to land’ came from Europeans.”

Once, while working in the forest, Cox says he unknowingly authorized felling a plot of timber where a local man used his sweat lodge.

“I felt awful,” Cox says. “I went to [another] department and asked, do we have a map of these sites?” They did not. “If we knew where those places were, we probably wouldn’t be going out with equipment,” he says, adding that his department needs, but does not currently have, a tribal liaison. Cultural sites can be easy to miss if you don’t know what you’re looking for, he explains, gesturing to an area where burial sites are located near the state forest.

But Cox says he opposes the land transfer because “[The White Earth Nation] has no experience managing public land. Allowing them would be a disservice to the public.”

While the White Earth Nation declined to comment on this remark, the Nation does oversee natural resource management efforts that affect public lands, such as a chronic wasting disease monitoring program and the Gidakiiminaan Environmental Program, which tracks air quality and pesticide use in coordination with federal and state agencies. The Nation’s natural resources and fish and wildlife departments host community workshops on tribal lands and engage in long-term restoration and stewardship projects.

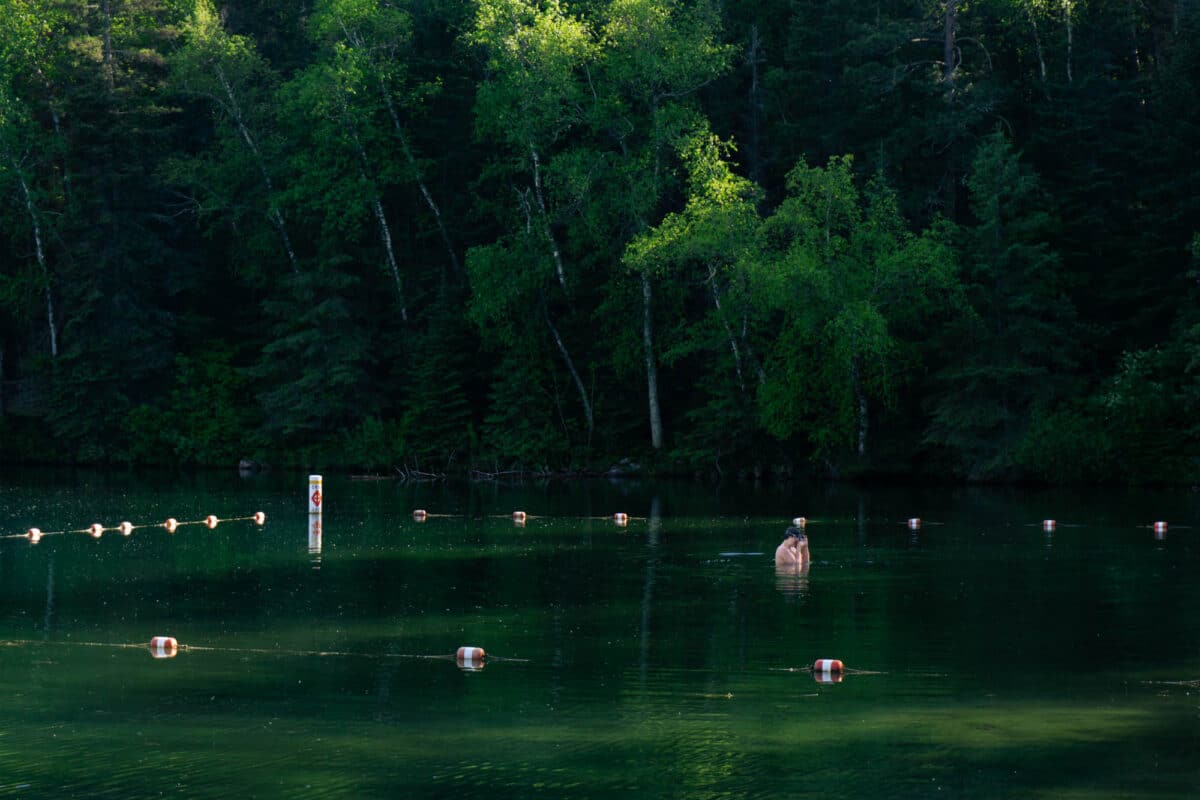

Wetland in White Earth State Forest.

Bruce Cox points to an area near Lower Rice Lake, just outside of the state forest, where access is restricted to Tribal members to protect burial sites.

During the land transfer bill’s initial hearing, Sen. Kunesh clarified that if the bill passed “all transferred land will remain open to Tribal and non-Tribal citizens.” The 34,874 acres of privately-owned land would “not be affected by this bill,” added White Earth Band Director of Resources Dustin Roy.

Even so, those opposed to the bill say that a future tribal leader could override these provisions and restrict public access, resulting in loss of recreational land access—and potential tax and timber revenue for counties and loggers currently operating on county-granted leases.

David Gerbracht, whose logging company operates in the state forest, says he is downsizing his operations in case a future version of the bill passes. “It’s not just one family, it’s eight or nine that depend on me” for reliable work, says Gerbracht, who opposes the transfer.

Freshly logged lands near the Buckboards.

Cox says that the public’s fear of losing recreational land access stems from situations like what happened at Heart Lake, a lake on tribal land just bordering the state forest that was once open to the public. After the tribe learned of people washing dirty ATVs in the lake, “which was a really irresponsible thing to do,” Cox says, the tribe closed lake access to non-tribal members. Cox says the issue was that the change had been sudden, and not up for negotiation.

Others view the transfer as unnecessary compensation for a moot history. “How long do we need to continue to pay for our ancestors’ wrongdoing?” wrote one resident of Mahnomen County in a round of public testimony. “History is just that, history,” wrote another.

The forest for the trees

On April 9, the Becker County Courthouse opened an overflow room to accommodate a flood of constituents who came to hear the land transfer discussion between the tribal and county councils.

Residents who testified in opposition to the transfer voiced concern about retaining public access to the forest. In response, Eugene Sommers, a district representative for the tribe, said that both the tribe and county want to keep the forest open to the public, but the tribe is “concerned about the actual existence of that forest.”

Tribal officials pointed out that the forest has dwindled “to one-third of what it once was,” under state ownership because of privatization, logging and agriculture. “Every time a piece of land is sold off, it is closed to the public,” wrote White Earth Chairman Michael Fairbanks in a message delivered to the Becker County City Council. The tribe emphasized that under their jurisdiction, the forest would continue to exist. (Chairman Fairbanks was unavailable for multiple interview requests.)

When Becker County Commissioner Erica Jepson proposed placing the state forest into a trust “so that the state could not sell any land off of it,” Sommers said he felt the county council was still missing the point. Ultimately, the tribe’s cultural and historical role as the land’s stewards makes them the rightful, most reliable legal caretakers of the forest.

That forest has taken care of us, what we’re trying to do is take care of the forest [in return] and to regain authority within our boundaries. Eugene Sommers

The return of the forest to the tribe would give the tribe the opportunity to implement a number of cultural, recreational and economic initiatives. It would also promote “generational healing, identity and self-worth” among tribal members.

“I hear a lot of state legislators talk about the state forest as a piece of land we need to make money off of, but that’s not how we view the forest,” Sommers told me later. “We view it as a living, breathing thing that has been vital to our existence. That forest has taken care of us, what we’re trying to do is take care of the forest [in return] and to regain authority within our boundaries.”

“The White Earth Forest is a culturally significant place to the Ojibwe people,”

Sommers continued, explaining that his own grandfather undertook traditional fasting periods and received his names in the forest—and that he hopes future generations will be able to carry out the same traditions on that land.

Cultural stewardship

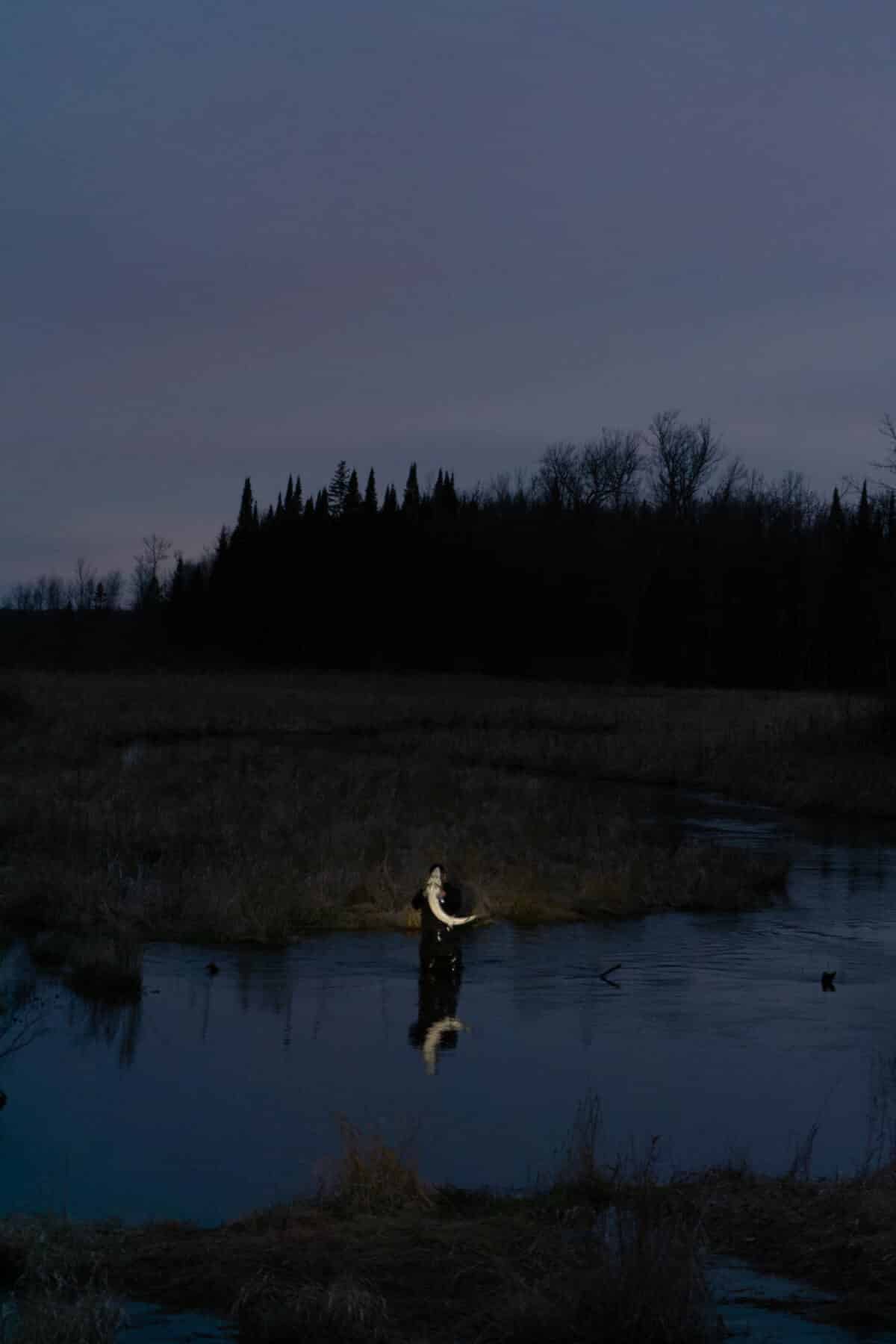

It’s easy to get lost in the White Earth State Forest. After losing cell service on my search for the White Earth Boys and Girls Club spearfishing workshop in early May, I drive to each place the road crosses Gull Creek on the map and finally come across a small crowd.

Despite the temperature falling to 45 degrees in the setting sun, the kids take to the water as if it is midsummer. From atop a culvert, Eugene “Umsy” Tibbets watches over the small crowd of headlamps bobbing in the dark. An excited shout erupts from the group of boys. They’ve spotted a fish. Tibbets flicks on his flashlight, spotlighting the water, and their pursuit ensues in a cloud of mud. The catch marked a significant milestone in the Tribe’s long-term land and wildlife management efforts.

Twenty years ago, the White Earth Natural Resources Department began reintroducing sturgeon to their native habitat within the White Earth Reservation after the species disappeared from the area in the early 1900s due to overfishing. For the educational workshop today, the White Earth Department of Natural Resources issued a single harvest permit.

“We don’t own the forest. We don’t own the land, we don’t even take care of it. It takes care of us,” says Sommers. He pauses to consider his words. “In return, we do things like harvesting wild rice in the traditional way: re-seeding and gathering rice at the same time. It’s just a point of view. The forest, to us, is autonomous. It’s like a relative, it’s like your grandmother, you know?”

Finding uncommon ground

On Mother’s Day weekend, many come to stare into the night as a record-breaking geomagnetic storm sent the aurora borealis bursting in green, pink and violet. In the White Earth State Forest, a lack of light pollution keeps skies dark enough to view events like these in their full brilliance.

The following Monday, a blanket of ever-more frequent wildfire smoke settles over northern Minnesota, reminding residents of years past when fires threatened to further cull the region’s remaining woodlands.

Yet summer splendor is nearly here. The fiddleheads have unfurled, fishing season is in full swing and families emerge triumphantly from the forest with sacks brimming with morels.

Zach Zornes, Laurie Hagen and her daughters Candy Watson and Shanda Hagen sit around an evening campfire on their family-owned land in the White Earth State Forest. Beside them are a pair of wooden crosses marking the burial sites of their father and grandfather.

Back in April, the Becker County hearing concluded after each council expressed an interest in working together as neighbors, but agreed to disagree on the method moving forward. While the county proposed developing co-stewardship methods, the tribal council maintained their stance about being the most reliable and rightful stewards of the forest. They remain committed to gaining complete jurisdiction and ownership of the land.

Ultimately, the fate of the bill boiled down to distrust between tribal and non-tribal governments, each dissatisfied with the other’s ability to effectively manage the forest land.

In documents detailing the first cessation of land by the Chippewas of the Mississippi, the bends and beginnings of lakes and rivers marked parcel borders. Today, you will see borders defined by neat sets of straight lines on two-dimensional maps. Borders between communities are far more dynamic. The coming years will tell how these communities might find continuity between a fractured past and what could become a hopeful future.