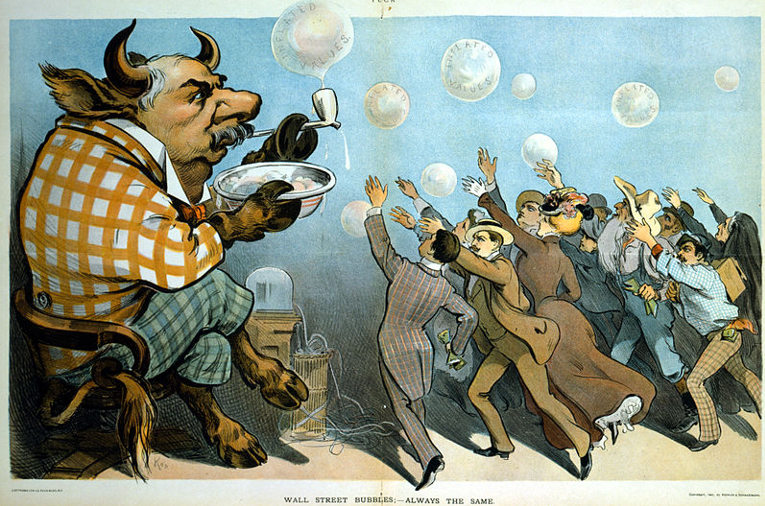

There can be few fields of human endeavor in which history counts for so little as in the world of finance. Past experience, to the extent that it is part of memory at all, is dismissed as the primitive refuge of those who do not have the insight to appreciate the incredible wonders of the present. Only after the speculative collapse does the truth emerge.

—John Kenneth Galbraith, A Short History of Financial Euphoria, 1990

All the recent talk about government Bitcoin reserves has gotten me thinking about what happens when governments speculate.

By the time governments decide to take the plunge to make money by speculating, whatever craze they are joining is likely nearing an important and very bad turning point that will lead to regret. This is because in their actions governments are by nature conservative in the ordinary sense of the word and tend to follow rather than lead investment trends after long delays. (Sometimes, as you will see below, the opposite happens: Governments sell assets at the bottom believing low prices signal that such assets are no longer useful or relevant. They thereby miss out on the next bull market.)

Government employees’ conservatism in action comes from being constrained by a web of rules that tell them what to do and when to do it. This is no more the case than in the management of government treasuries. That money is there to be spent on things the elected representatives decide to spend it on. In the meantime, it should be invested in low-risk securities with a very low likelihood of default, and that usually means investing in government securities of short duration. That also means low returns. But accepting such returns is said to be justified by the desire to make sure no money is lost.

Not surprisingly, it takes a lot to infect a government money manager with speculative fever. But it helps if the fever has already spread far and wide in the public. This is because so many come to believe that those without the fever are suffering from a mental defect that is causing them to miss out on a development that will lead to a healthy, even grandiose, financial future.

Enter Robert Citron, treasurer for Orange County, California from 1970 to 1994. His was a sleepy job until late in his career when Citron was enticed by Wall Street banks to invest substantial sums of the Orange County treasury in highly leveraged securities that would benefit from stable or lower interest rates.

Citron thought he would be allowing tax-averse Orange County residents to have a continued high level of services without any rise in taxes. At first the money rolled in, so much so that he had to hide the profits by transferring them to various pools of money he controlled (so that he would not arouse suspicion that he might be doing things which were against the rules). But when interest rates rose sharply in 1994, Citron’s strategy blew up. This forced Orange County into a bankruptcy that led to severe cuts in the county workforce and thus its services.

As it turns out, what Citron was doing wasn’t exactly legal (the “web of rules” mentioned above) and he ended up spending a year in jail.

It also sometimes happens that government officials miss important opportunities for such mundane reasons as “diversification,” sometimes spelled “diworsification.” That’s what happened to Gordon Brown when he was serving as Britain’s chancellor of the exchequer (the equivalent of finance minister in most parliamentary systems).

Brown thought it would be good for the government of Great Britain to diversify its reserve holdings by selling some of its gold and buying foreign currencies (which unlike gold pay interest). Between 1999 and 2002 he managed to sell half of the United Kingdom’s gold reserves at some of the lowest prices seen since the mid-1970s, namely between $250 to $350 an ounce. Just six years later the gold futures price topped $1,000 and after slumping during the Great Recession, it hit nearly $1,800 in 2012. Today, the price stands at more than $2,600 an ounce.

Unlike Robert Citron, Gordon Brown’s misstep didn’t hurt him. This is probably because he didn’t actually lose money, but rather caused the government to miss out on a handsome profit opportunity that few people noticed. Brown went on to become Britain’s prime minister.

In another time and another place, the state of West Virginia and its local governments were blindsided by steep losses in a fund run on their behalf that pooled idle cash for combined investment. The state investment board managing the pool had a wild west mentality which governments investing in the pool appreciated so long as they were getting returns that were far above market interest rates. But the party ended in 1987 when interest rates rose abruptly and the pool managers got caught flat-footed. Instead of owning up to the losses, they lied and doubled down by borrowing money to speculate even more to make up the losses. At one point they had borrowed $11 billion against the pool whose value was only $2 billion. It didn’t work.

The state treasurer who oversaw the pool was impeached.

By now you must be wondering whether attempts at speculation by governments might be a reliable contrary indicator. For those unfamiliar with this term, it refers to purchases or sales made by market participants who are regarded as being especially feckless, so much so that their purchases or sales are taken to be a sign that one should do the opposite. Gordon Brown’s gold selling spree turned out to be a nearly perfect contrary indicator. Buying gold from Brown at around $250 a ounce in 1999 and holding it would become one of the best trades of this century so far. Likewise, betting that interest rates would rise when Robert Citron bet they would stay the same or fall would have at first tested your liquidity and your resolve, but in the end richly rewarded you. The same might be said of the West Virginia debacle.

Which brings me to the suddenly proliferating idea that governments ought to set up Bitcoin reserves. Newly elected President Donald Trump has spoken favorably about establishing a federally funded Bitcoin reserve. A Texas legislator is proposing that the state have one, too. As the momentum has built in anticipation that large new buyers in the form of governments will enter the Bitcoin market, the price of Bitcoin recently hit record highs above $100,000. Where were those governments when Bitcoin surpassed the lowly price of $500 in 2016? Or when it surpassed $1,000 in 2017 reaching above $17,000 before the year was out?

Governments weren’t interested then because Bitcoin seemed risky back then. But, of course, risk is relative to price. If you buy when the price is low, there is less room between you and zero. But investors tend to run in herds toward the latest thing that’s going up. Whatever you think of Bitcoin, there is a lot more room between the current price and zero than there used to be. And there is a much bigger public mania surrounding it now than back in 2016 or even 2017. By the way, public mania over a particular investment is another one of those contrary indicators.

While I am no gold bug, it is worth noting that if you get stuck with physical gold after a price crash that wrings out much of the premium that investment demand creates, there is intrinsic value left. Gold has many industrial purposes (electronics of all kinds, dentistry, aerospace, glass that reflects sunlight) and, of course, it is always in demand by those making and selling jewelry. The same cannot be said for exotic leveraged interest rate derivatives sold by Wall Street investment banks. Nor can one make Bitcoin into into rings, bracelets or plating for high-quality electrical connectors.

So, I’m asking myself whether the Trump administration and the state of Texas will go down in the annals of contrary indicator history as calling at least an important top in Bitcoin (followed by the inevitable crash). Economist John Maynard Keynes is reputed to have said that the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent. Bitcoin may indeed be headed to someplace closer to the Moon in the short run. But I suspect that gravity has not been repealed on Earth or in financial markets and that this moment or one coming up shortly will put the timing of the establishment of a U.S. government Bitcoin reserve in the history books—because of the crash that follows.

P. S. The only country that I know of that has established a Bitcoin reserve is El Salvador where Bitcoin is legal tender. El Salvador just recently concluded a $1.4 billion loan agreement with the International Monetary Fund, and the IMF cautioned the government to limit its purchases of Bitcoin.

P. P. S. I own no investment that will benefit from price movements either up or down from any of the investment vehicles mentioned in this article. Also, I tend to be early (sometimes uselessly early) when predicting market tops—which is why I take Keynes’ admonition about staying solvent seriously.