This is the second-part of my climate-not-all-bad-news series, beginning with the state of the U.S. Here I turn to China, a paradoxical story of both immense challenges and great hope.

Growth as the world has never seen

It is the nation that holds the world’s climate future in its hands.

It is the nation whose 2014 commitment to peak climate pollution by 2030 made possible the 2015 Paris Climate Accord target to cap global heating at 1.5°C.

It is the nation which has made keeping that commitment most challenging, being responsible for 90% of the growth in global carbon dioxide emissions since 2015.

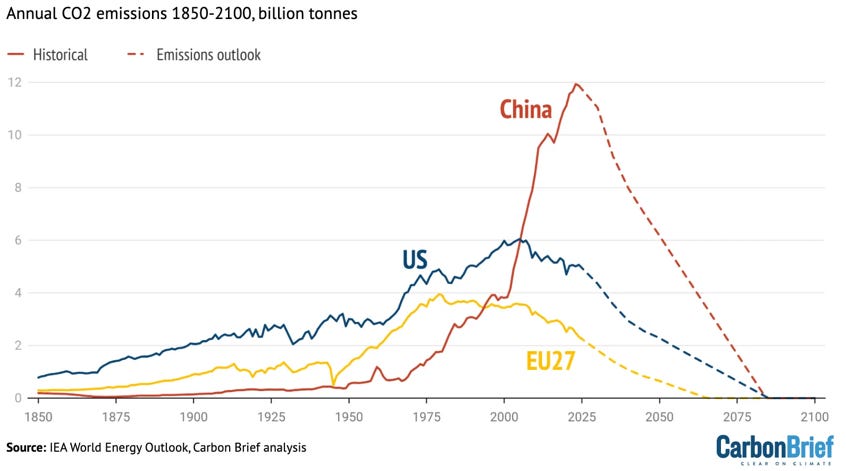

It is the nation whose rapid deployment of clean energy technologies may peak its climate pollution this year or next, offering the best chance for holding to at least not greatly overshooting the Paris commitment.

It is China, whose economic surge over recent decades has exceeded anything the world previously witnessed. China is now the world’s largest economy by purchasing power, with 19% of global output. In real terms it is over a quarter larger than the United States. Even that might understate the case.

China has experienced

“the greatest development surge in human history driven above all by an unprecedented and spectacular surge in urbanization,” writes historian Adam Tooze. “As a physical productive apparatus China completely dwarfs the United States (and any other comparator). China’s total electricity generation is twice that of the United States. China’s steel production is ten times that of the USA. China’s cement production is more than twenty times that of the USA.”

Tooze concludes, “It is China’s story, more than any other, that defines our current horizon of expectation and the scope of our current possibilities.”

“China is the worldʼs greatest emitter of greenhouse gases, therefore the countryʼs ambition in its climate agenda is decisive for keeping the international community on track for a 1.5°C or 2°C pathway,” notes a recent report from the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA). “China is responsible for 30% of global GHG emissions and more than 90% of the growth in carbon dioxide emissions since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015. Chinaʼs emissions have more than quadrupled over the past two decades, making it the primary driver of global emissions growth over the period.”

Though China is the world’s largest exporter, growth of the domestic economy has also played a significant role in emissions growth. CREA says industrial growth to supply export markets was the biggest player from 2000-8, but since 2009 building construction, infrastructure expansion and industrial development for domestic consumption have been the largest contributors.

China may be peaking now

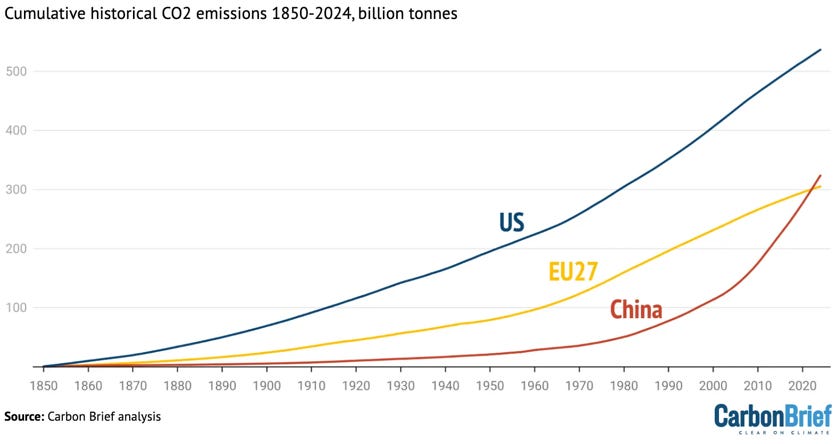

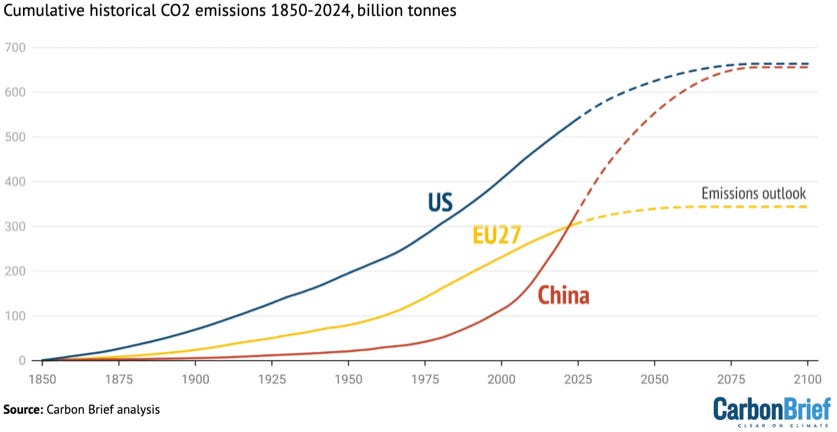

Historic emissions, the cumulative contribution of climate-twisting gases over time, demonstrate how significant China has become to the global climate picture. Carbon Brief calculates China’s have now surpassed those of the European Union.

U.S. and EU emissions have been declining for some years, and will continue to do so, even in the U.S. under Trump. The momentum of clean energy technologies is now too strong, as I wrote in a recent post.

But China’s overall emissions might never exceed those of the U.S., underscoring the huge responsibility the U.S., still the world’s second largest climate polluter, bears for reducing its climate pollution.

Still, whether the world has a shot at the 1.5°C target, or at least not going too far beyond that, depends on how quickly China peaks and reduces its climate pollution. China is slated to announce its 2035 target this coming February.

CREA’s survey of experts finds an increasingly optimistic perspective. Asked if China’s emissions have already peaked this year or will by 2025, 44% responded yes, up from 15% in 2022. Over 70% believe China will certainly achieve its 2030 peaking goal.

Importantly, 52% say China will peak coal consumption by 2025. The addition of over 200 new coal plants in recent years is a major reason for the surge in Chinese emissions. But only 9 GW of new plants were approved in the first half of 2024 compared to 52 GW in the same period last year. Similarly, a slowdown in addition of steel capacity – China makes over half the world’s steel – and move to greener and more efficient alternatives is a reason for optimism.

Building most of the world’s solar and wind

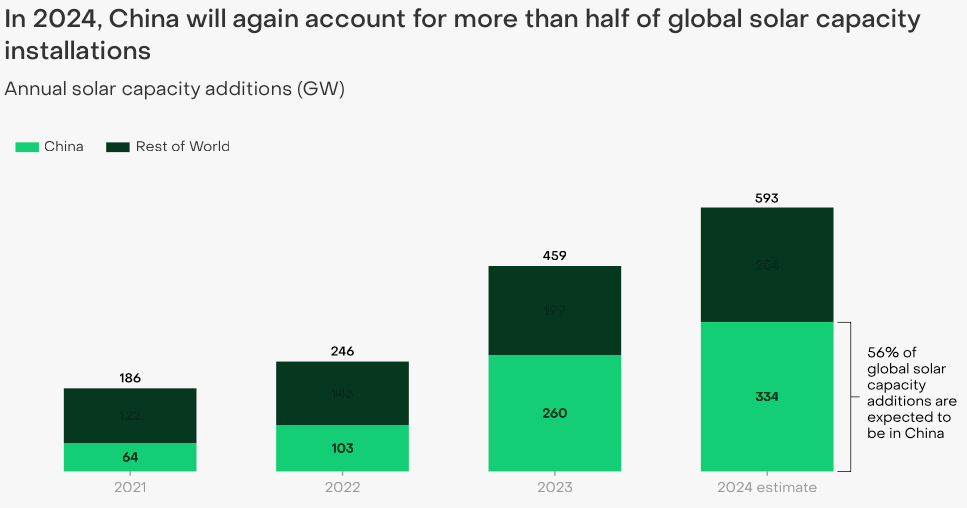

The greatest source of increasing optimism is China’s renewable energy boom, whose boggling scale has already exceeded its 2030 growth targets for wind and solar energy. In 2023 and 2024, China installed the majority of solar photovoltaic capacity, reports Ember. In 2023 it was 260 of 459 gigawatts, and in 2024 224 of 593 gigawatts.

Credit: Ember

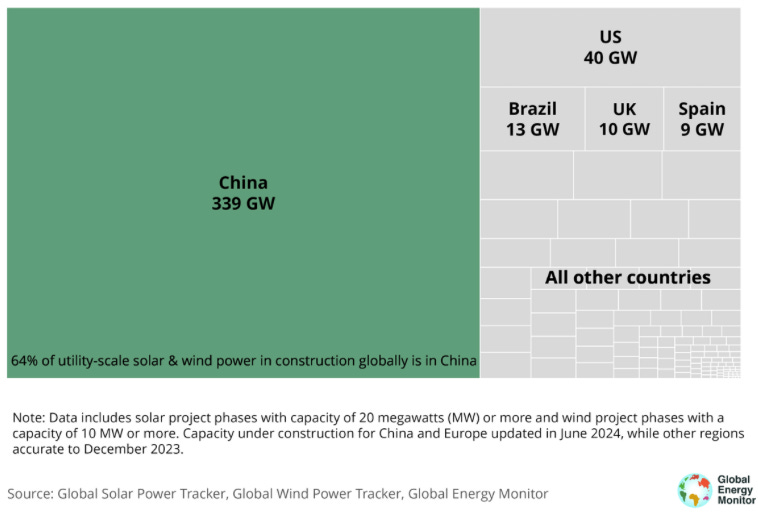

Putting together the picture for Utility-scale wind and solar growth, China’s lead over the rest of the world is stunning, accounting for 64% as of July 2024, Global Energy Monitor reports.

“China added almost twice as much utility-scale solar and wind power capacity in 2023 than in any other year,” says Global Energy Monitor. ”By the first quarter of 2024, China’s total utility-scale solar and wind capacity reached 758 GW, though data from China Electricity Council put the total capacity, including distributed solar, at 1,120 GW. Wind and solar now account for 37% of the total power capacity in the country, an 8% increase from 2022, and widely expected to surpass coal capacity, which is 39% of the total right now, in 2024.”

In fact, clean energy is taking up the slack for the downturn in China’s real estate sector, which has been an important source of the nation’s growth. Clean energy accounted for 40% of economic growth in 2023, CREA reports.

China on a 1.5°C track?

But will China be able to continue? On the plus side, utility-scale solar has now become the cheapest source of power in the Asia-Pacific region, its lifetime cost dropping 13% below coal in 2023 and expected to be 32% less expensive by 2023, Wood Mackenzie reports. Adding in battery storage to firm up power supply, utility-scale PV is competitive with gas generation now, and will be competitive with coal by 2030.

The critical issue is grid capacity.

“The key constraint on clean-energy growth will be the ability and willingness of grid operators to integrate very large amounts of clean energy,” writes CREA lead analyst Lauri Myllyvirta, also a senior fellow at Asia Society Policy Institute, China Climate Hub.

He continues, “Last year, numerous provincial grid operators began to limit additions of new wind and solar, due to concern over not being able to fully integrate the additional generation . . . The challenge is that China’s grid management is outdated. Reforming grid operation requires overcoming powerful interests, most notably the owners of coal-fired power plants who are reluctant to accept the reduced space for coal-power generation that follows clean-energy growth.”

On the other side of the equation are local governments, which on the China scale rank in population with many European countries. They have been a dynamic factor in pushing renewables forward as a rural economic development strategy.

China could cut its carbon pollution 30% by 2030 compared to 2023 if it achieves certain goals, CREA projects. Continuing its solar and wind growth could give the nation 3,500 GW of renewables by 2030 and 5,000 GW by 2035. Overall non-fossil electricity could amount to 65% of supply by 2035, putting that sector on a 1.5°C Paris path.

Reducing transport emissions to 2020 levels by 2035 would align that sector with the Paris target. That would require that 60% of auto sales be electric vehicles, not a far reach from the 50% level of EVs and plug-in hybrids. The share of freight going by rail would have to increase to 25%.

Industrial decarbonization is crucial. The largest source of growth in energy use from 2020-3, 4% annually, was government emphasis on energy intensive industries such as steel and chemicals to recover from the pandemic and downturn in other sectors, notes Myllyvirta. To stay on the Paris track, industrial emissions must decline 25% from 2023 levels by 2035, CREA says. That includes 45% in steel. China’s nationwide emissions trading system recently included steel, aluminum and cement, so that should help, CREA says.

Finally, building sector emissions could drop 40% by 2035 with elimination of coal use in buildings, still substantial, as well as low-carbon standards in new buildings, retrofit of 25% of old buildings, and heat pump penetration of 40%.

China has demonstrated remarkable capacity to rapidly make major changes. It also has a major stake. Notes CREA,

“Swiss Re, the worldʼs largest reinsurer, assesses that China is among the countries most affected by the economic and physical impacts of climate change, ranking far above regions such as the European Union and North America. At the same time, as the worldʼs largest greenhouse gas emitter, Chinaʼs own energy and climate policies have a major bearing on the severity of the climate impacts the country will face.”

China has its own fate in its hands, as well as the rest of the world. We can hope it will take the needed actions that will give us a fighting chance to hold at 1.5°C, or near it.