This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news

Farmers like Dustin Watson are turning toward new land-centered models to overcome the challenges of farm transfer and succession

Dustin Watson looks over the pastures and woodlands he grew up on. Behind him is the farmhouse his great-grandfather built, not far from the chicken coops and tractor sheds his grandfather raised decades ago. Cattle graze near one of his favorite places on the farm, the tree he was recently married under. It’s a rare moment of rest for a man who doesn’t often sit still.

Talking slowly with a soft drawl, the 36-year-old Watson describes his family’s farm in Greene County, Virginia, about 30 miles north of Charlottesville. It has flat, open hay fields and fertile pastures for grazing livestock. It’s split in two by a ravine, which adds diversity and depth to the landscape. Two creeks flow through the property and empty into the Rapidan River just across the road.

Dustin Watson calling cattle on his family’s farm in Greene County, Virginia.(Gillian Watson)

The farm is in a rural community but close to several towns and conveniences, from restaurants and big box stores to hotels and golf courses. Drive northeast for 100 miles and you’ll be in downtown Washington, D.C. Look west from the property’s highest hills, and you’ll see the Blue Ridge Mountains and Shenandoah National Park.

“It’s everything you would look for in a farm,” Watson says of the 274 acres, painting a vivid picture of his place. “Except for four and a half years when I went to Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, I’ve spent my entire life here.”

Watson’s devotion to the farm is palpable. He loves the land, and he is grateful for the opportunity to care for it. Yet because of a challenge with succession planning and farm transfer—a difficult dynamic that’s all too familiar for many farm families throughout Virginia and across the country—that opportunity almost vanished.

According to research from American Farmland Trust, roughly 300 million acres (or 468,750 square miles) of farmland are set to change hands in the next two decades. As current farmers age and exit the field, the future of about a third of the United States’ agricultural land is unclear.

Transitioning a farm from one generation to the next, whether that transition occurs within or outside of a family, can be a complicated process. It involves a dizzying combination of economic, legal, and emotional challenges, all of which combine to increase the complexity of an already taxing task.

This complexity means that, when the time comes, farmers and families sometimes feel as if their only choice is to sell the place quickly on the open market, often the easiest and simplest option but not always the one that is best for the family and the land. Maybe the current farmers want to retire, and they need to convert their biggest asset—the land—into cash; or perhaps the person who has been tending the land dies with no solid plans in place to pass down the farm.

Plant a “for sale” or “auction” sign in a field that used to grow crops or forages. Worry about the changes to life and landscape. Wait and see what happens next.

In our current moment, farmland is being converted to real estate development at an alarming rate. “Farms Under Threat 2040,” a 2022 report by American Farmland Trust, projects that the United States is on track to convert nearly 20 million acres of irreplaceable farm and ranch land by 2040. That’s an area nearly the size of South Carolina that will be turned into strip malls, housing developments, data centers, low-density lots and warehouse fulfillment centers.

What land remains is often purchased by established farmers looking to expand their operations. With these dynamics, it can feel like one’s fate is sealed when transitioning a family farm. That’s the case even if there is someone young who yearns to take over. It’s a reality that puts current and aspiring farmers in a tough position.

This describes Dustin Watson’s situation with his family’s beloved Long Acre Farm. His great-grandfather O.P. Shiflett first bought the farm in 1939. As O.P. aged and later passed away, his son Randolph and daughter-in-law Lorene Shifflett took over the farm. (The last name is spelled differently between generations—“That’s how it was in the holler,” Watson says.) They raised commercial broiler chickens and beef cattle for decades. Like all farms, Long Acre was susceptible to the ups and downs of the agricultural economy, but it generally did well.

Then, Randolph Shifflett’s health declined. He struggled to care for the livestock and land, and the family decided to sell the chickens. As his health worsened, they began to sell off the cattle herd, too.

“My grandmother had to sell the cows to pay for their expenses,” Watson says. “They were getting older and couldn’t work.”

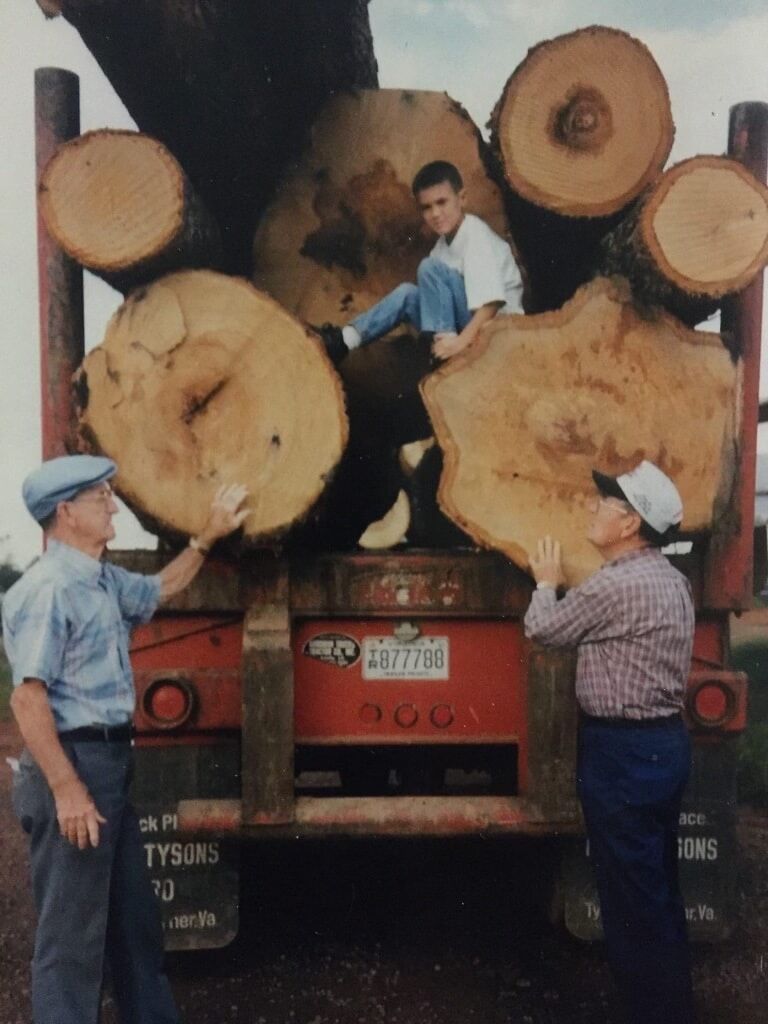

Dustin Watson as a child with his great-grandfather, left, and grandfather. (Courtesy of Dustin Watson)

Randolph passed away in 2009, and Lorene became the sole owner. A few years later, in 2015, she died. In the weeks and months after her death, the farm’s future became uncertain.

“My grandparents had two children: my mother and my aunt. When my grandmother died, everything was left to the two of them, 50-50. But it was all undivided interest, and it didn’t say who got what,” Watson says.

Watson badly wanted to farm the land, and in fact, he had already begun to do so. In 2010, when he moved home after finishing college, he bought a few head of cattle, put them on the farm, and started to acquire the necessary equipment to steward the land and animals. His mom—one of the two co-owners—was content with this arrangement, but his aunt, who didn’t live near the farm and felt less connection to it, wanted to sell.

Watson was young, not yet 30 at the time. He didn’t have the means to purchase his aunt’s share of the farm. After all, the property’s prime location near the growing city of Charlottesville made its value soar. Real estate developers were, and still are, scouting the area to purchase farms and transform them into subdivisions, large-lot residential housing and commercial uses.

Virginia’s population growth and sprawling real estate boom have put pressures on rural landscapes. Conservative projections suggest that the state could lose nearly 600,000 acres of farmland between 2016 and 2040 if current trends continue. That drives up the price of remaining land, making affordable farmland access an even greater challenge for young people.

Watson’s aunt generously gave him a few years to come up with the funds. “In order to buy her share out, I basically needed to come up with a million dollars,” Watson says. “I tried to manage my money and do the best I could, but a million dollars is kind of hard for a blue-collar guy to come up with.”

As he still does now, Watson worked a full-time job off the farm to earn extra income, a necessity for most American farmers. He scrounged and saved where he could. And he started to develop plans. He called agricultural lenders and local banks, pursuing several different loan opportunities. But with the property’s high price tag and his limited savings, he repeatedly struck out.

By the fall of 2022, Watson started to worry. He felt lost and scared. “This is more than a piece of land,” he explains in a quiet, serious voice. “It’s also my family’s legacy.” He had made promises to his grandfather and his grandmother in their dying days that he would keep the farm going, that he would do whatever it took to forge ahead. But he was afraid that his promises might be broken, that the legacy might be lost.

Desperate, Watson started calling different organizations. He dialed up Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI) and spoke with them.

“I’m a big Willie Nelson fan,” he says, laughing, “so I went to the Farm Aid website and called their hotline. I told them my story, and they were just about crying by the time I finished.”

Both organizations shared helpful resources, but Watson still felt stuck.

On a whim, he called his local Virginia Cooperative Extension agent, Sarah Sharpe, again to ask for help, and he finally struck a lead. She had just attended a community meeting hosted by the Piedmont Environmental Council (PEC). The meeting was focused on conservation easements and how they can help farmers. Specifically, presenters talked about how farmers could be compensated for selling their land’s development rights to a public conservation program, ensuring that a farm would always remain an open agricultural space. Why not give them a call, Sharpe suggested.

Watson had heard of “donated” conservation easements before, where landowners can receive income tax benefits for protecting their land. But he wasn’t aware of these purchased options. Once again, he picked up the phone.

He spoke with the team at PEC, and they shared information about the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service’s ACEP-ALE program, or the Agricultural Land Easements component of the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program. These are federally funded, entirely voluntary conservation easements, PEC staff explained. They could give Watson an influx of cash while also ensuring that Long Acre would remain a farm forever, protecting its soils, wildlife habitat, scenic value and productive capacity.

For the first time, Watson started to feel like he was on a promising path. The funds from the conservation easement wouldn’t be enough to purchase all of his aunt’s share, and it might take some time for the deal to be completed, but it was a start. Finally, it seemed, he was moving in the right direction.

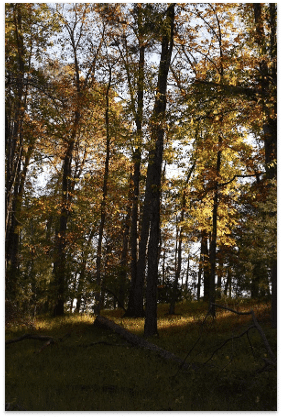

Light in autumn on Long Acre Farm. (Gillian Watson)

But his aunt was ready to sell now. By this point, she had been waiting for five years. She wanted to move on.

“We had put in a proposal for the funding from the ACEP-ALE program,” remembers Mike Kane, PEC’s Director of Conservation, “and it was accepted, which was fantastic. And then we secured some funding from the Virginia Land Conservation Foundation.”

Aware that Dustin still needed additional funds to help make the deal go through, Peter Hujik—a former member of Kane’s team at PEC—got in touch with American Farmland Trust (AFT), a national conservation organization that also works on the ground in Virginia. (Full disclosure: the author works as Land Protection & Access Specialist at American Farmland Trust.)

After meeting with Watson and PEC, AFT agreed to provide a bridge loan to help Watson cover the costs of purchasing his aunt’s share of the farm.

“At AFT, we work to protect farmland and ‘keep farmers on the land.’ That’s in our mission statement,” says Alison Volk, who serves as the Director of Buy-Protect-Sell Plus and Easement Acquisitions at AFT. “When we first met Dustin, we were struck by his commitment to the farm and his family, and we really wanted to help.”

Jen Perkins, AFT’s Mid-Atlantic Farmland Programs Manager, agrees.

“These are the kinds of projects we dream about, where we get to team up with a trusted partner like PEC to achieve something extraordinary.”

With combined support from PEC and AFT, not to mention his own hard work and perseverance, Watson was able to buy his aunt’s share of the farm, securing its land and legacy. Against long odds, he kept his promise to prior generations that Long Acre Farm would continue.

In doing so, Watson has helped highlight an encouraging model for successful farm transfer processes, one that centers land protection as an effective transition strategy.

He hopes his experience will highlight not only the challenges of farmland transfer but also the innovative ways that families can transfer land and keep it in production, whether in his home state of Virginia or in communities across the United States. AFT’s national “Land Transfer Navigators” project, an NRCS-supported multi-year partnership with dozens of other conservation groups to address farm transfer challenges, intends to uplift Watson’s story as a case study.

An agricultural conservation easement may not be right for every farm or farmer. The permanent nature of these agreements may be unappealing to some. In fact, that was initially the case for Watson. He was hesitant, and he shares that many of his farming friends and neighbors are, too. Even for those who are less hesitant, the time it takes to complete a farmland protection process can be a barrier. While they can move quickly, conservation easements are complex deals that sometimes take years to finalize.

Yet evidence shows that these legal tools help facilitate farm transfers: a 2023 report reveals that 72% of survey respondents who participated in a federal farmland protection program said that the protected status of land was “very or extremely important” in their transition process; 39% said the same about the proceeds from the easement transaction.

For those like Watson who hold the land and its meaning dear—and who would benefit from an influx of cash without having to sell off acreage, livestock or equipment—agricultural conservation easements can be an effective strategy. As with other farms throughout the country, this tool enabled Long Acre to survive.

A foggy day at Long Acre Farm. (Gillian Watson)

“I wasn’t going to give up,” says Watson. “But I’ve got to admit, I had my doubts. I didn’t think [keeping the farm] was very realistic. Then it actually happened.”

The process wasn’t simple, and it sure wasn’t easy. Watson admits that he’s tired, physically and mentally. As a farmer with a full-time off-farm job, the work and stress never stop. Yet reaching this point has also given him an opportunity to pause and reflect.

If things were planned out a little better when my grandfather was in his prime,” he says, “if I didn’t have to put all my efforts into just keeping this place, maybe I could have put those efforts into improving my family’s farm.”

It’s a lesson, even a warning, for others. But Watson doesn’t dwell on what could’ve been.

“There are small family farms and ranches that are struggling all over the country,” he notes. “I just want ‘em to know that there is hope out there. There’s good people that have got your back and want to help and want to see you keep your family operation going. … I mean, I was fortunate enough that I was born into a farm family, that I have this background. Some people don’t grow up around farming, but it’s always been their dream to start a farm.”

“If that’s what somebody really wants to do and if they don’t give up on it,” Watson says, “if they want to carry their family farm on or start a new farm themselves … they ought to know that where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

If you are a farmer, landowner or service provider who would like to learn more about protecting or transitioning farmland, either to the next generation in your family or to a young farmer outside of your family, please visit: https://farmland.org/land-transfer-navigators/