Elections are always complicated things, although pundits sometimes try to pretend that they’re not. In this post I run through some different narratives or ‘explanations’ of Trump’s victory that I’ve noticed or heard since Wednesday and pull out a quote or add some commentary.

1. It’s the economy, stupid

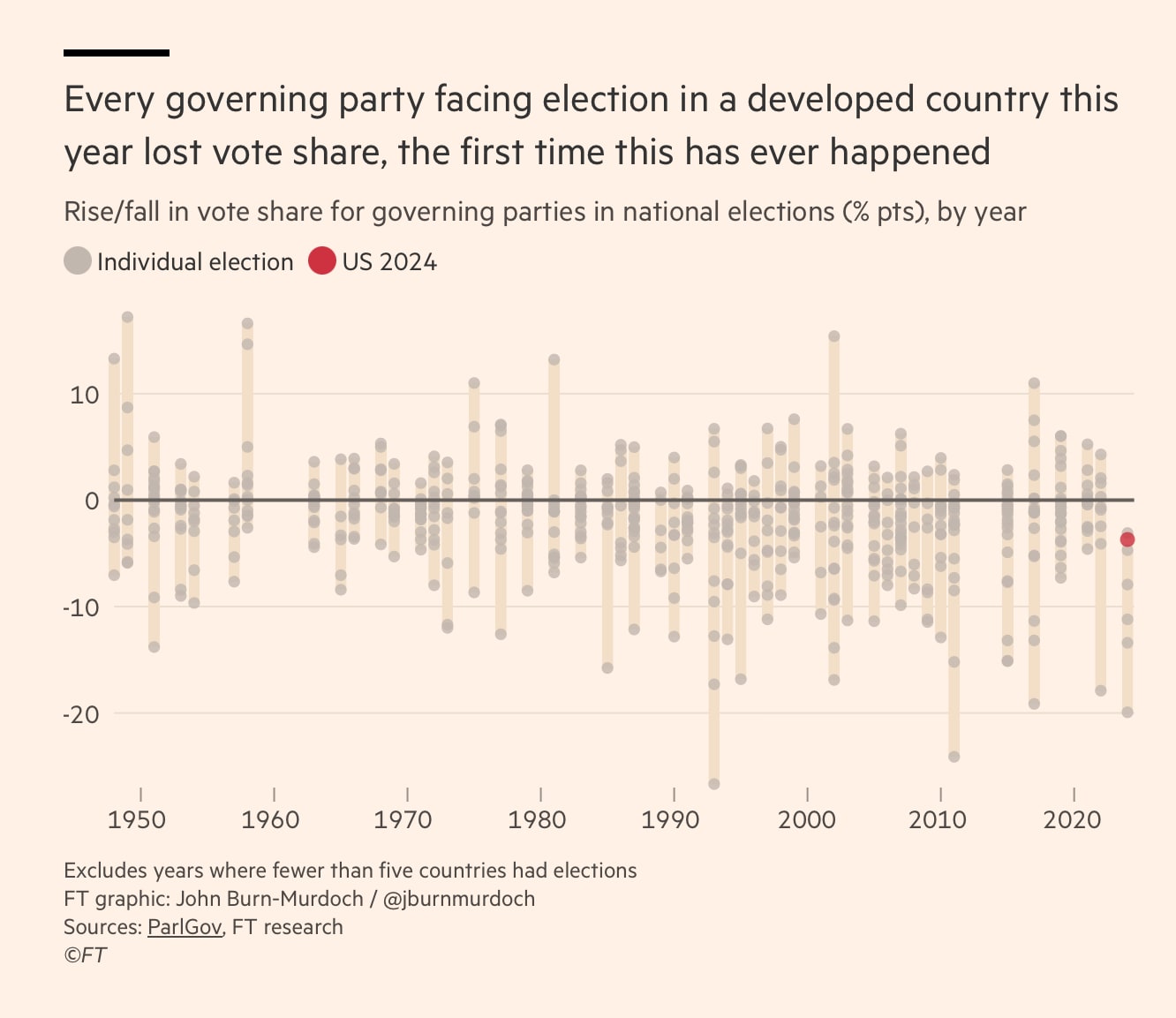

One of the more persuasive charts on the election was shared by John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times. In the elections that we have had this year, the incumbents have lost vote share, for the first time, going back to 1950. The scale of Harris’s defeat wasn’t that large when looked at against that global set of results.

(Source: John Burn-Murdoch, Financial Times)

(Source: John Burn-Murdoch, Financial Times)

The moral of this chart, for Burn-Mudoch (probably paywalled), is that:

Ultimately voters don’t distinguish between unpleasant things that their leaders and governments have direct control over, and those that are international phenomena resulting from supply-side disruptions caused by a global pandemic or the warmongering of an ageing autocrat halfway across the world.Voters don’t like high prices, so they punished the Democrats for being in charge when inflation hit.

The German-born but US-based economist Isabella Weber, who’s done quite a lot of research on inflation, noted on Twitter than governing parties can survive high unemployment but that they can’t survive high inflation, probably because high inflation affects everyone.

Burn-Murdoch concludes that since the governments that were defeated this year campaigned in different ways and on different platforms, “a large part of Tuesday’s American result was locked in regardless of the messenger or the message.”

There’s more on this—looking at both Biden’s failure to respond to inflation, and the failure of the Harris campaign to distance itself from this[1]—in a newsletter by Matt Yglesias.

2. There’s a gender war going on

This isn’t just about abortion. This is about men. I’ve written about the masculinity crisis in the United States and elsewhere here quite a lot, so I’m not going to labour this point here too much. (This is a relevant post from last year).

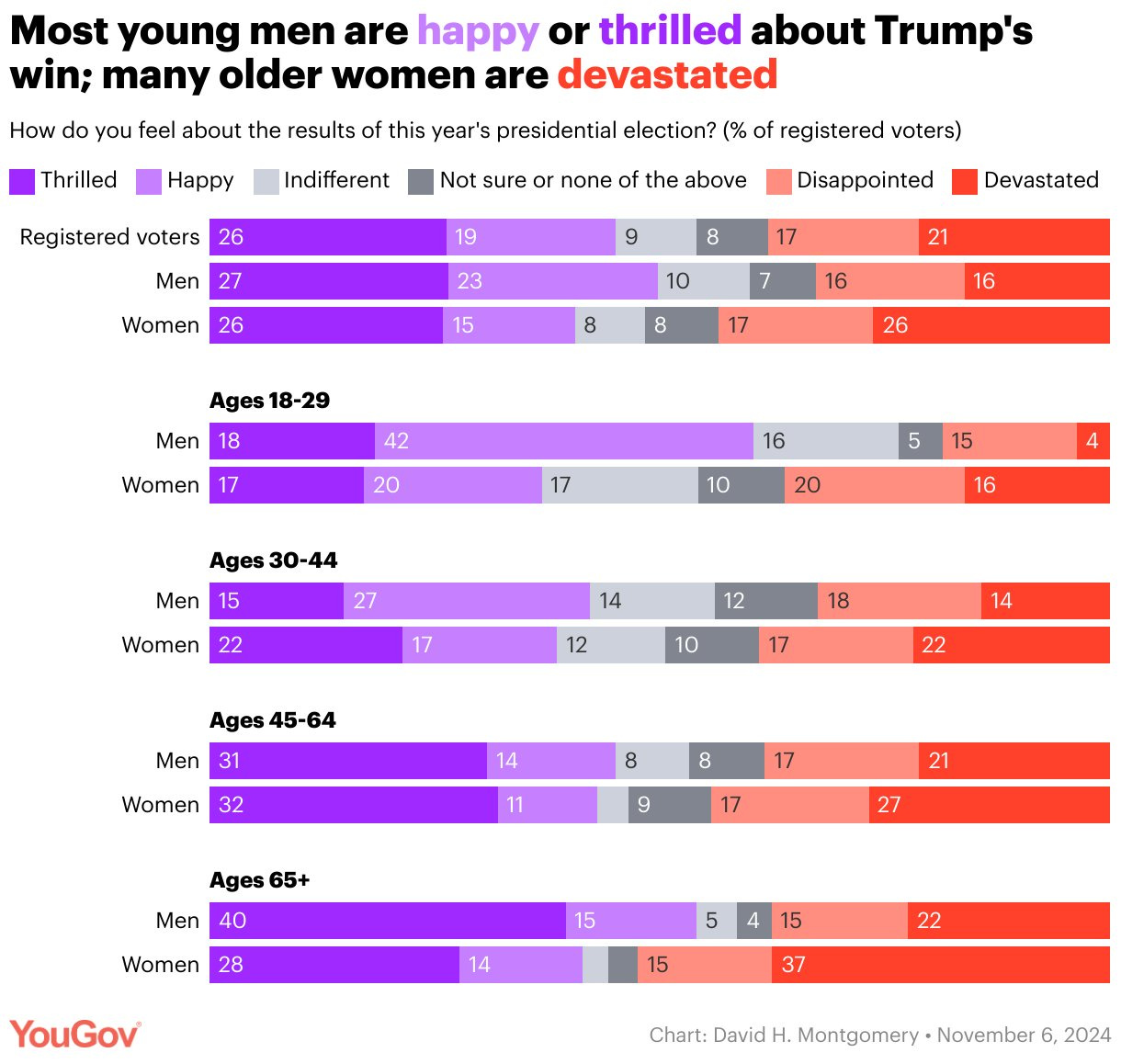

But there was one striking chart published after the election by YouGov—so, to be clear, this is post-election polling, not voting.

(Source: YouGov)

There’s a lot of bar charts on here, so in summary, the purple lines show people who are thrilled (darker purple, left hand end) by Trump’s victory, or happy (lighter purple).

‘Devastated’ and ‘disappointed’

The darker red lines (right hand end) show people who are devastated, the lighter red lines show people who are disappointed.

The big gender differences are among the 18-29 year olds and the 65+ group. In the younger cohort, men are more likely to be thrilled/happy than women by 15 percentage points, and young women more likely to be disappointed/devastated by 17 percentage points.

In the 65+ group, older women are more likely than men to be disappointed/devastated by 15 percentage points.

Looking at the data, what is it that connects first wave feminism with fourth wave feminism? The gender differences in the two age cohorts between them are real, (i.e. on the face of it likely to be beyond the margin of error) especially when you look at the numbers for ‘devastated’, but the gaps are much smaller. It would be great to understand the qualitative insight that sit behind these findings, and I imagine that this will emerge over time.

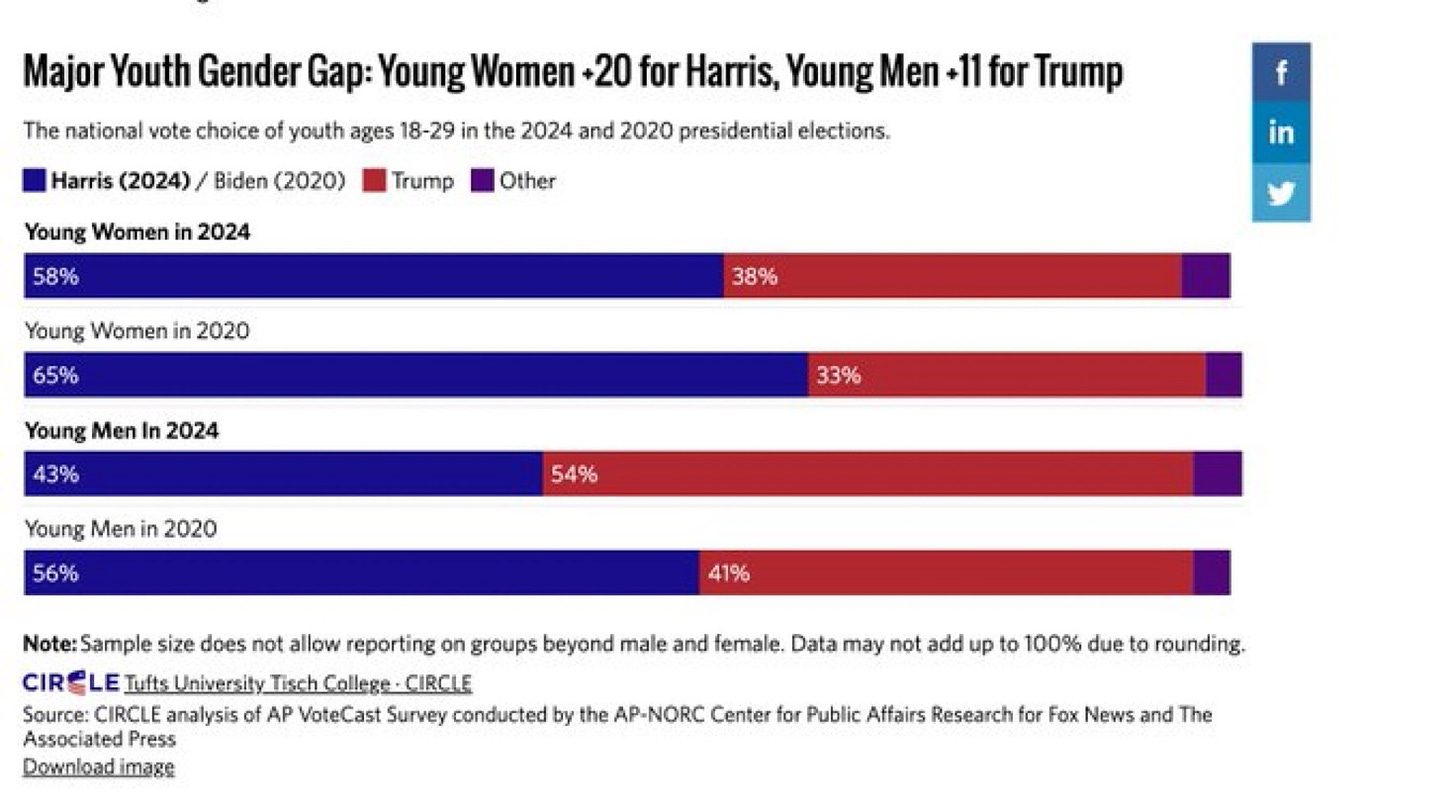

There’s also some voting analysis of the younger cohort (also using an 18-29 age break) by the AP NORC Centre for Public Affairs Research.

Source: AP NORC Centre for Public Affairs Research)

Source: AP NORC Centre for Public Affairs Research)

There’s a decline in the proportion voting for Harris in 2024 compared to Biden in 2020 (see: It’s the economy, above). But the young men have switched from pro-Democrat to pro-Trump.

A woman’s life

One chart I saw, which I wasn’t able to save, suggested that some of this might be economic as well. Young men’s earnings did very well under the first Trump Presidency, but they have—across the Biden years—more or less flatlined (up, then down, then up.)

Anyway, Jia Tolentino went into this subject in a piece in The New Yorker from which I’ll pull a couple of quotes here:

Both campaigns leaned into the gender war… as pitched by politicians, [this] revolves around two competing visions of a woman’s life. Each side thinks it understands what the other wants. The Trumpists… believe that the left wants women to be Plan B-gobbling dilettantes in their youth; dick-stomping corporate drones in early adulthood; lonely, angry spinsters who approach forty in a mania for egg-freezing or emasculation…

The libs believe that conservatives want women to spend their youth in training to attract, submit to, and please men, suppressing all other forms of human potential… The chasm between young men and women in this year’s vote is the chasm between these two stories.

Tolentino notes, by the way, that these stories have little to do with women’s lived experience in America: there’s little divergence between Democrat and Republican women:

What baffles me about this supposed contest between ideas of womanhood, both of them invented by men for political purposes, is its distance from the reality of living as a woman… Two-thirds of Republican mothers work outside the home; the percentage is only three per cent higher for Democratic mothers. Democratic women have their first child at twenty-five, on average, just one year later than Republican women.

3. The Democrats have become the party of the elite

The radical Vermont senator Bernie Saunders attracted ire from quite a lot of quarters when he said that the Biden administration had “abandoned the working class”. Your view of this largely depends on your definition of “abandon”, and I should note here that the Democrats disagree robustly.

There’s a ton of internecine Democrat party politics sitting behind this, going back at least a decade, which I don’t have space to rehearse here. A familiar critique of the Obama Presidency is that he talked about hope but cosied up to Wall Street (see Ry Cooder’s song about post-crash bankers for reference.) And when you get into campaign minutiae, there’s a critique of the Harris campaign that says it lost momentum at the point that it stopped talking about economic measures because of pressure from business elites.

The economist Daren Acemoglu—a recent winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize for Economics—squared off these two views in a note:

Biden’s economy delivered for the working class in terms of jobs and strengthening the industrial base of the country. Wages at the bottom rose rapidly. Policy started moving towards the views of the American workers on immigration, protectionism, support for unions and public investment. And yet, I fear that Dem activists and the establishment never fully internalized the woes of the workers and never made enough of an effort to bring them back to the fold. They sounded distant and detached.

Either way: it’s worth sharing an interesting graphic of votes against income here.

Via Twitter: source unknown. (Let me know if you know who I should credit)

And another, of votes against income and education levels, and its change over the last quarter of a century, from the data journalist Patrick Flynn.

Source: Patrick Flynn, focaldata.

A post that I can no longer find says that, perhaps because of this, when Harris said, ‘We must defend democracy’, voters heard ‘I will keep the status quo’. The journalist Chris Hedges put it more strongly:

the election was about despair… The stagnation of tens of millions of lives, the realization that it will not be better for their children, the predatory nature of our institutions, including education, health care and prisons, have engendered, along with despair, feelings of powerlessness and humiliation. It has bred loneliness, frustration, anger and a sense of worthlessness.

4. Trump is a vision of America revealed

There’s a long piece by the New York Times writer Carlos Lozada, which seems to be outside of their paywall, which suggests that America should accept that what Trump represents is a picture of America—just one that his critics do not like to acknowledge to themselves. It is headlined, ‘Stop pretending that Trump is not who we are’. (H/t to John Naughton’s Memex 1.1 blog for this link).

In recent years, I’ve often wondered if Trump has changed America or revealed it. I decided that it was both — that he changed the country by revealing it. After Election Day 2024, I’m considering an addendum: Trump has changed us by revealing how normal, how truly American, he is. Throughout Trump’s life, he has embodied every national fascination: money and greed in the 1980s, sex scandals in the 1990s, reality television in the 2000s, social media in the 2010s. Why wouldn’t we deserve him now?

You can make more of this: a friend sent me an email reminding me of the similarities between the United States and Russia:

[T]here’s a horrible mirroring of USA and Russia, in their colonising histories and geographies, and in the tendency to gigantism in extraction and production… Both infected with the idea that modernity and growth are limitless, and that they’re born to rule as specially ordained superpowers.

Deserving to fail

In The Nation, its Justice Correspondent, Elie Mystal, doubled down on this broad idea:

We, as a nation, have proven ourselves to be a fetid, violent people, and we deserve a leader who embodies the worst of us… America willed Trump into existence. He was created from our greed, our insecurities, and our selfishness…

Mystal’s version here is that Trump is a reflection of ourselves: for those that love him, he tells them it’s OK to be who they are. Those who hate him see an image of their worst selves: Trump is the return of the repressed.

Everyone who hates Trump is asking how America can be “saved” from him, again. Nobody is asking the more relevant question: Is America worth saving? Like I said, Trump is the sum of our failures. A country that allows its environment to be ravaged, its children to be shot, its wealth to be hoarded, its workers to be exploited, its poor to starve, its cops to murder, and its minorities to be hunted doesn’t really deserve to be “saved.” It deserves to fail.

5. Trump is an expression of the rise and rise of the ‘dream society’

One take on all of this is that our present wave of politics is floating on a transition from an “information society” to a “dream society”. The idea of the dream society was developed by Rolf Jensen of the Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies more than a quarter of a century ago. The underlying idea is that the ‘information society’ of the second half of the 20th century was a world in which

“knowledge becomes more important than capital,” and in which “numbers are better than words because they are concrete; they reflect measurable, physical realities.”

In contrast, in the ‘dream society’ individuals will think

of oneself as part of a greater whole, finding meaning in the mundane, and using icons and mythology to create guideposts for navigating the world.

Jensen—writing when social media was no more than usenet groups—expected that this change would be largely benign. Earlier this year, the veteran futurist James Dator published a book called Living Make-Belief: Thriving in a Dream Society which revisited the idea. (It’s vastly expensive: clearly Springer doesn’t expect people to buy it.) From the publisher’s summary:

Ongoing social and technological forces are pushing us from a world of words, rationality, and truth into a world of images, performance, and make-belief.

‘Schtick, performance, and make-belief’

I don’t have access to the book, but Dator posted some thoughts about Trump on a listserv I’m a member of; it’s a private listserv so I’ll keep this extract brief:

Most Americans (and other humans) live in an emerging dream society where consciousness and action are dependent on whose side you are on, and not on what is real or even plausible… Trump and his billions are the wave of the future—a dream society beyond the old information society where facts and logic matter. What matters now is schtick, performance, make belief, sometimes all-too-bloody-real, but usually just for the fun of it.

This connects, perhaps, with a thought that Rafael Behr had in a column in The Guardian. I’m not a fan of his writing—usually he is just an effective conduit for the current UK political consensus—but he argued here that the right had modernised as communications were transformed, but people who supported the values of democracy had not.

A democratic election is the antithesis of an internet transaction. It contains not just an expectation of delayed gratification, but a guarantee of frustration… The alternative is a political movement, such as the Maga cult, that treats elections as a cry of rage or exultant self-actualisation.

He concludes by suggesting that liberal democracy “has undergone no obvious renewal since its peak at the end of the last century.” I’d go a step further: its response to the extended series of crises of the 21st century is that it has gone backwards (see [3], above, about elites).

6. The final, final, end of the post-war settlement

I don’t have time to do more than sketch this out here, but one of the ideas that sometimes floats around in the long wave futures world is that eighty years, or so, is a meaningful span of time for institutional systems. It’s an under-researched idea, and some of the versions of it that depend on generations are spuriously precise. But what sits behind the model is a version of the ‘panarchy’ cycle—collapse, build, enjoy, unravel.

And what might sit behind it as a mechanism, more or less, is a generational effect in which working lives last for around forty years; the first half as a junior, the second half as a senior.

But: it’s impossible not to notice that we’re now eighty years on from the great wave of multi-lateral institution-creation that followed the end of the second world war, and that the United States has just re-elected a President that thinks every bit of that set of institutions is meaningless bunk, rather than a mechanism for American soft (and hard) power.

The eighty year idea has a tweak in it—after 40 years it starts to buckle and gets re-invented in some way.

A rough sketch here of the post war years might first take us to 1971, when Nixon crashed the Bretton Woods’ monetary system by abandoning the gold standard. Then through to the mid-80s, when Reagan and Thatcher deregulated the global financial system, and the surge of neoliberalism that went with it—along with increasingly hawkish behaviour by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

(Thatcher and Reagan in Downing Street, London, in 1984. Photo: via Levan Ramishvili/flickr, public domain.)

(Thatcher and Reagan in Downing Street, London, in 1984. Photo: via Levan Ramishvili/flickr, public domain.)

Unresolved issues

And then wind forward to the global financial crisis (perhaps more accurately the Atlantic financial crisis), which itself followed a wave of regional financial crises over a ten-year period, signs of the system juddering.

Almost all of our current politics is still in the shadow of the unresolved issues arising from the global financial crisis, sixteen years on. But they are exacerbated by some of the ‘solutions’ to the financial crisis, such as the way that quantitative easing led to ballooning asset values that makes housing increasingly unaffordable and elites increasingly rich. And sitting behind this, a forty year period in which we were more interested in enabling rentier capitalists to prosper rather than doing anything meaningful about climate change.

At a workshop I was facilitating last week, some of the participants talked about people’s ‘sense of loss’, at least in the global North, for a more secure world that was never coming back again. On this reading, ‘solastalgia’ is about more than climate change; it’s about a whole psychic landscape. Trump has caused little of this. He—and the other right wing leaders we see across the global North and elsewhere—are symptoms.

—

[1] The Republican pollster and political consultant Frank Luntz, who doesn’t have skin in the Democrats’ developing blame-game, identified this failure to distance from Biden (on economics and on Gaza) as the Harris campaign’s biggest error.

Of course, that takes you in to questions of character about the steeliness at the heart of every successful politician. The lateness of Biden’s decision to withdraw also meant that Harris was played a poor hand and that the Democrats didn’t hold primaries that might have allowed a more effective candidate to emerge. But given the failure to deal with inflation these might all be distinctions without a difference.

—

A version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.