Nearly four decades ago, a large team of scientists from around the world launched a major global research programme called the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP). Their goal was to study the connection between human activities and changes to the earth’s biological, chemical, and physical systems, and in 2004 they synthesised the results of their initial research phase in a 336-page report entitled Global Change and the Earth System. The report revealed that humanity was causing a series of unprecedented changes that were pushing ‘the Earth System well outside of its normal operating range’.

Never before had the world’s atmosphere, land, coastal zones, and oceans experienced change at the rate that was now occurring. This was ‘a no-analogue situation’ according to the IGBP authors, and raised the very real threat of catastrophic, non-linear, events that could destroy the natural systems on which the survival of humanity depends.

Twenty years have elapsed since this report was issued, and the casual reader might be forgiven for dismissing it simply as an interesting historical artefact – one more example of an urgent warning ignored in a long road of climate inaction. But the IGBP synthesis made one distinctive and path-breaking observation that remains highly relevant today: something happened around the middle of the twentieth century.

The significance of this turning point is confirmed by the report in a series of iconic ‘hockey-stick’ graphs, which show environmental markers such as atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide beginning gradually to increase from the 1750s, and then suddenly exploding around 1950.

As Ian Angus points out, the timing of this ‘Great Acceleration’ surprised the lead authors, who had expected to see changes to the earth’s systems follow a steady, linear trend starting from the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century.

Instead, the IGBP report concluded: The second half of the twentieth century is unique in the entire history of human existence on Earth. Many human activities reached take-off point sometime in the twentieth century and have accelerated sharply towards the end of the century. The last 50 years have without doubt seen the most rapid transformation of the human relationship with the natural world in the history of humankind.

Why was the mid-twentieth century the turning point in humanity’s impact on the earth’s systems? The simple – but incomplete – answer is oil. Oil first began to emerge as a significant energy source in the US during the early 1900s, although, at the time, coal remained the dominant fossil fuel. A major leap towards an oil-centred world occurred around the Second World War, when the shift from coal to oil was extended across Western Europe, and then later through newly industrialising countries in other parts of the world. The oil transition massively accelerated the world’s consumption of fossil fuels and thus carbon emissions: nearly three-quarters of the human driven increase in the atmospheric concentration of CO2 has happened since 1950, and about half since the 1980s.

Despite hopes of another great transition towards renewables, oil remains by far the world’s most important energy source today, making up around 40 per cent of all fossil fuels consumed in 2022 and one-third of the world’s primary energy (renewables constituted slightly more than 7 per cent).

As the world’s most traded product, oil’s economic power also remains indisputable. Measured by revenue, four out of the six biggest companies in the world are oil companies, and in 2022, the Saudi Arabian oil giant Saudi Aramco made history by recording a profit of over $100 billion – the largest profit made by any company, in any industry, ever.

Oil, in other words, remains at the core of our economy and our energy systems; without dislodging it from this position there is no possibility of ensuring a future for humanity. The focus of this book is the story of how we find ourselves in this predicament – with the hope that this might tell us something about what must be done to dismantle the fossil economy.

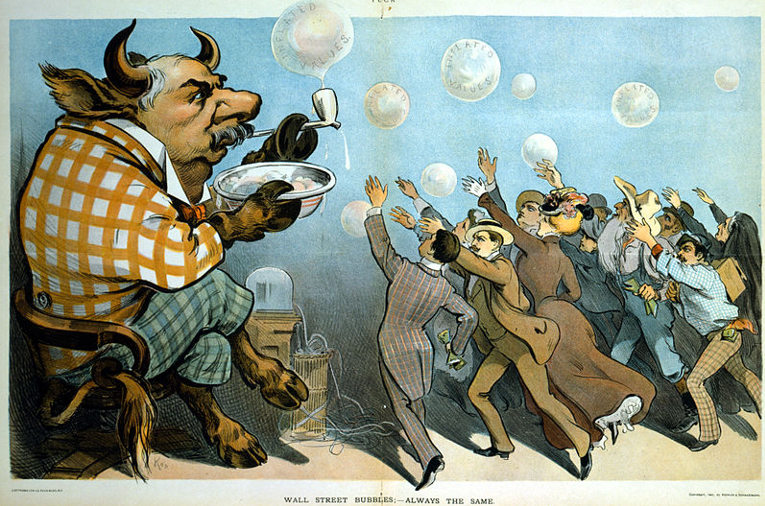

But the approach taken here breaks with the way oil is usually written about. Too much of our everyday thinking about oil invests it with some kind of inherent magical power, capable of transforming and changing societies by its presence (or absence) – a kind of ‘commodity determinism’, in the words of Michael Watts.

This power is seen in the various labels often used to describe oil: a ‘prize’, ‘curse’, ‘devil’s excrement’, and so forth. Now, oil certainly does provide incredible wealth for some and has simultaneously been enormously destructive for others, but the problem with this way of thinking is that it ascribes a causal power to oil itself, which, at the end of the day, is simply a sticky black goo. The real secret to the oil commodity lies instead in the kind of society that we live in – the priorities, logics, and behaviours that derive from how society is currently organised.

These social relations are what give oil meaning; they are where oil’s apparent ‘power’ comes from. As the title of this book indicates, the ‘kind of society that we live in’ is referring here to capitalism. Capitalism’s internal raison d’être is one of endless accumulation – a drive to continually accumulate money that overrides all other considerations. This social logic differs from all preceding human societies and has had a profound impact on energy use and energy systems. A starting assumption of this book is that, without foregrounding capitalism as a social system with its own distinct logics, we lack any explanatory reason for why and how oil emerged as the dominant fossil fuel through the twentieth century (and even more importantly, what must be done about it). The problem with most conventional writing about oil is that this historical uniqueness of capitalism as a social system is ignored – in fact, capitalism rarely makes an appearance. The result is to naturalise the social system we currently live under. In turn, the emergence of an oil-centred world is treated as a self-evident outcome of oil’s material qualities (such as its high energy density, transportability, and efficiency).

Put differently, oil’s power is assumed to derive from the natural properties of the commodity itself, separate from the social system that gives these properties meaning and significance.

The story of oil then falls back into descriptive narratives focused on the attempt to control this magical commodity: tales of swashbuckling early oil entrepreneurs, the intrigues of the major Western oil companies, or the geopolitical tussle to capture a supposedly scarce resource.

*This is an extract from the new book Crude capitalism: Oil, corporate power, and the making of the world market by Adam Hanieh