In my previous article, I discussed, based on recent research and my own experiences, how one must take the social life of smallholders in developing countries into account in order to understand how and why they work and exist. They are not smallholders only, or even primarily, for economic reasons but they also appreciate other aspects of being smallholders, such as the social values of land, landscape and farming, the countryside as a place for care of children or elderly and the village as a buffer in times of crisis. They also appreciate the clean air, the joy of work, the good environment and the social relationships.

In this article I want to discuss to what extent the experiences from developing countries apply to smallholders in the so-called developed countries (those that use most of the planet’s resources). For simplicity, let’s call that the North.

It is hard enough to define smallholders in the context of developing countries and even harder in the North. There are also quite some differences between the various countries of the North with Japan and USA as two extremes. When I visited Japan last year, I saw many paddy fields so small that no farmer in Sweden would even bother ploughing them, and apparently a number of farmers still practiced manual harvest of the rice, even though most small farms in Japan are highly mechanized. In the USA, a cattle farm with 100 mother cows is considered small by the US Department of agriculture. Sweden, where I live, is somewhere between those extremes.

Clearly it is not about size of the land that is worked. There are small farms of just a few hectares with greenhouses that employ a hundred people and there are farms with hundreds of hectares of rough grazing which can’t even feed a family. There is a dwindling share of smallish traditional farms which barely keep a family alive on mainly farming activities while there are many farms that combine farming with various other income generating activities, be it a normal day job or selling services to others. There are also several categories of “new” smallholders.

Some of them, like myself, are people without a farming background that practice small-scale farming, often with an aim to be rather self-sufficient in food and energy. Others are regularly retired or part of the FIRE tribe (those that earn and save a lot in order to quit working early) and pick up farming as a hobby, for landscape management or a meaningful thing to do. Mostly, they engage either in cattle breeding or wine growing rather than the production of vegetables or staple foods.

In my view the smallholder, or peasant, of the North has most of the following characteristics:

- She does most of the work on the farm herself or with her family (or other household constellations).

- She doesn’t manage the farm primarily as a commercial venture but as a way of life.

- She is restrictive with the purchasing of inputs.

- She consumes a certain share of the production of the farm herself.

Most of the characteristics of the smallholders of developing countries apply, in varying degrees, to smallholders of the North. Because of the almost total privatization of land in the North, the link to the land is often strong but the link to the village or local community is considerably weaker than in the cultures where land is still communal.

Keeping autonomy: resisting commodification and market integration

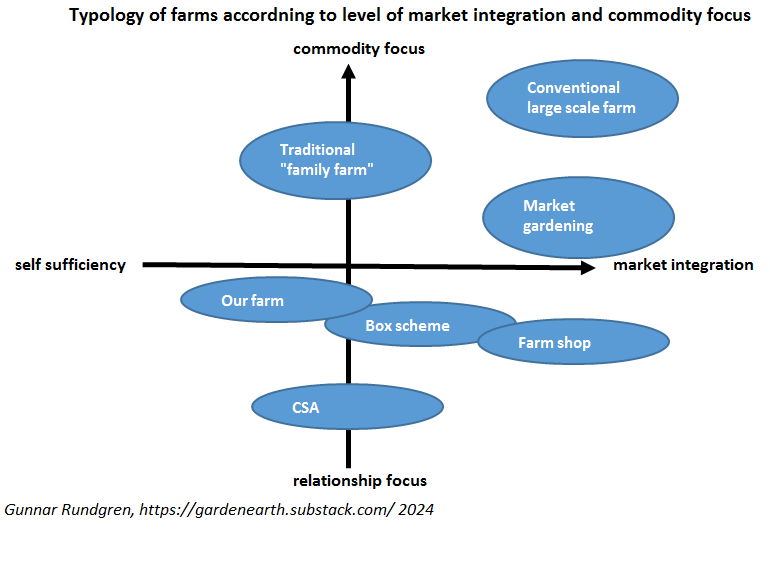

Autonomy is a central theme for smallholders, both as a means to keep options open and a planned strategy of resistance to commodity farming, industrial farming, capitalism, call it what you like. Even in the supposedly ultra-commercialized USA, 16 percent of the small scale mother cow operations have no clear economic motive for their production but they do it because they like it. In Sweden 17 percent of the sheep farmers keep sheep without producing any lamb, as they are not interested in producing meat. In the graph I try to categorise some versions of farms, including ours, according to the level of market integration as well as the extent of commodity focus.

Having other income streams than farming is not only because you can’t live on small scale farming (you can’t) but also a way to allow you to run the farm according to your ideals rather than to the dictates of the market, banks or the government. A “day job” can in that way strengthen the autonomy or at least the feeling of autonomy. Being rich is just another version.

Other ways to shield the farm from the pressures of the market is to build relationships with a tighter knitted group of people, such as in the concept of Community Supported Agriculture. In those, relationships replace transactions.

Early in 2023, I visited farms in the region Waginger See in Bavaria. Most of the organic farms I visited had a diversified production oriented to the local market. The one with the most diverse production was also a community supported agriculture farm, in German called Solidarische Lantwirtschaft. This farm, Blümlhof grows all kinds of vegetables and fruits, rye and dinkelwheat and has sheep cows, donkey, pigs, bees, chicken, horses and what not. They are three families working together and have some 50 “co-farmers” as they call the members of the CSA. Those commit 160 euros per month for a year at the time. For that they can take as much as they want of the harvest, the milk, the meat, the honey and the eggs pending availability of course, following the old principle “to each according to their needs”.

Elke and Hubert Hochreiter at Blümlhof, photo: Gunnar Rundgren

As land consolidation has gone very far in many countries in the North, access to land is an obstacle for the establishment of new small farms. I plan to write more about it in the future, meanwhile I can recommend these two articles.

Transforming land for sustainable food: Emerging contests to property regimes in the Global North by Adam Calo and colleagues, and

Moving toward a fairer access to land fostering agroecological transition? A decade of legal change and reframing of debates around soil and climate in France, by Adrien Baysse-Lainé.