The following excerpt is from Nick Kary’s Material: The Art of Handcrafting Beautiful Objects in a Digital Age (Chelsea Green Publishing, September 2024) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

The following excerpt is from Nick Kary’s Material: The Art of Handcrafting Beautiful Objects in a Digital Age (Chelsea Green Publishing, September 2024) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

I wonder if the ripples in a veneer on the surface of a table can speak of the tree that they were cut from. If a tree could speak, what would it say? Are we so different from a tree, blood and sinews or sap and cellulose – matter transformed to life, and then to death and decomposition? Death hastened by an interaction with time and air, lives lived through action and perceived inaction, words sanctifying the human and separating all else. I am not a tree, nor could I be, too impatient to stand for so long in one place and allow the force of the wild earth to run through me. I wonder of the stories, of magpies that bury their dead, albatrosses mating for life and mourning the passing of the first to die. Human language imposes itself on the natural world, as do my words here, a thirst for meaning, for what it may mean to live a shared life.

I have allowed my words to form this book, and allowed them to form me as well. The materials from which I have crafted furniture, by which humans have established their dominion here, are those through which my words have grown. We craft objects with material, books with material and we clothe ourselves with material. I have found materials on my journey through the writing of this book, which have helped me understand my place. The writing process is a craft that has a direct association with our well-being, with our understanding and belonging.

Some years ago I signed up for a master’s degree in Creative Writing for Therapeutic Purposes (CWTP), an attempt on my part to explore my belief in the value of the writing process as much as the value of its product. The table crafted by the furniture maker is forever a symbol of a relationship with the material they made it from, and the journey to its completion. A book, it strikes me, is much the same: a product for the enjoyment of others which represents the processes of the writer, and their distillation of the materials they draw on. The course was run by Claire Williamson, and it was to her house I found myself journeying some time ago, having not seen her for some years.

I had read her poetry, knew a little of her story, of what had pushed her to reach into her creative depths and express herself in language. I loved what I had read, her candour and the pacing of it through the constructs of metaphor. It created a fine thread of personal connection that promised something for the future. So I reached out to give that thread a little tug.

She heard me, and the thread resonated back, strengthened just a little each time one of us plucked it. I found her house on a balmy summer day, and stepping out of the car alongside a garage entangled by weeds, I allowed time to stand still, expectations to fade. A low metal gate, stiff drop latch amenable to my touch, stone steps leading me to the front door. Catching a movement to my right, the drift of words, and excited action of a wagging tail, I veered towards it and found two men sitting in the sun on the stone paving. I was pointed back to the front door, and soon Claire was standing there, as ever I had remembered her. Our warm embrace spoke of a new relationship; the threads had rewoven into a fine and strong rope. A young dog fought for my attention, and successfully commandeered a little of it.

Time spent around the kitchen table as Claire prepared a salad helped to braid a rope bridge over the three-year gap that we could cross easily. We spoke with ease of things that could not be spoken of before: of our children, of the delicate balance of our own paths with those reliant on us, of our creative edges and the place we found for them. Claire and her partner, Andrew, had moved to this old house three years before, and at lunch I heard from Andrew’s father, a retired architect, of its history, the life it had lived or the one they had reimagined for it. As we ate we looked out over the River Severn, motorway bridges spanning its width, wind turbines around Avonmouth sentinels to a distant view.

We moved back into the cool of the house, to Claire’s great book-lined workroom, computers arrayed on desks. She splits her time between organising the courses, teaching, facilitating CWTP sessions and writing. Moreover she’s doing a PhD around the subject of bereavement, a subject that finds form in her writing. I am here because I have questions about the craft of writing, of the material that that craft draws on and of its creation of a physical form, a body of substance, an entity, if you like, similar to the product of a potter’s craft.

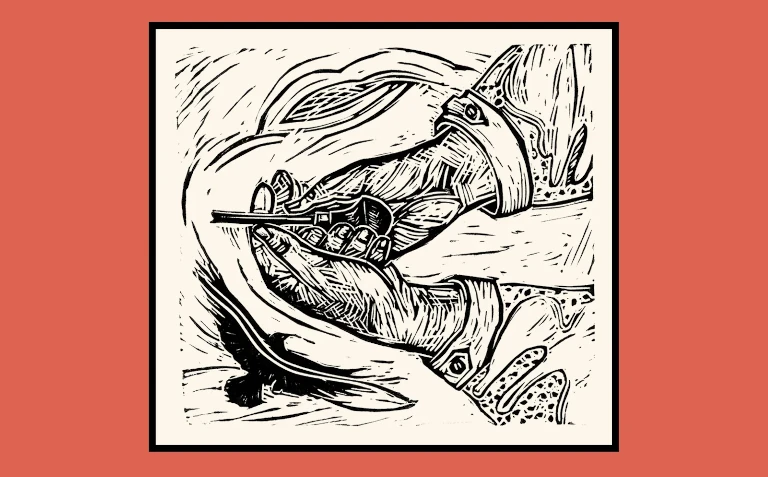

It had struck me that as I talk about making through the experiences of others and myself, I am giving expression to this through the act of writing. The path unfolds in front of me, and there is no corresponding map for it. I follow a hidden track and find where it leads me. So here I am in Claire’s office, not sure exactly what it is that I will find. I have come to Claire’s front door much as I might have gone to a timber yard or to a tree lying in a field. I am not entirely sure of the form that tree or the planks from it will take. But one thing I do know is that they are material for the journey that will unfold around them.

This book is a fluid path from an idea, along a stream bed whose variations, detours and eddies are unknown until the water that flows into it finds itself moved. So, too, is much of the work I do now, inspired as it is by the material, the planks or trees, it moves from them into a notion of what it might become. But that is not exactly what it does become; meanwhile there is a trust that whatever emerges will be the right thing to have emerged, becoming the object that could not be seen but that is right.