The belief that you can create healthy ecosystems by payments for environmental services or ecological compensation is akin to believing that you can buy love by visiting a prostitute.

In my previous article, I discussed the (blessing and) the curse of the straight line, and concluded that we need to find ways to moderate our demands on nature. I ended my article with saying that “capitalism, modernism and consumerism do not like limits or restrictions.” I will look into markets and capitalism in this article, into science in the next one and in the final one individual behaviour and culture (at least that is my plan, sometimes when writing new ideas pop up and new perspectives emerge).

While humans have changed the environment for a very long time, with the joint introduction of capitalism and fossil fuels more than two hundred years ago the scale of this human impact has grown tremendously and mostly in a negative way. Many still put their faith in that capitalism and markets also will “fix this”. When discussing markets one has to differentiate between voluntary markets, markets created by governments and economic incentives of various sorts.

I have worked with voluntary markets for environmental improvement for many decades in the shape of markets for organic agriculture products. For sure, it has had quite some success, but by and large the ability of these systems to change the system radically is limited. In the end, organic agriculture is more changed by the markets than they have managed to change the food system. In general, consumer demand is not particularly efficient in dealing with problems that are rooted in fundamental structures of society, the market and the economy. They do normally work well when they are about a simple substitution of a technology, e.g. chlorine-free paper or CFC-free fridges. But things like that can – and should – be accomplished by mandatory regulations. I expand the discussion on voluntary sustainability standards in the article Can we shop our way to a better world.

Putting a price on nature

Many scholars have pointed to the need for internalization of social and environmental costs and compensation for ecosystem services as the silver bullet for overcoming market failure. Perhaps the most known example of voluntary markets for this is voluntary carbon trading, or “climate compensation” as it often is called nowadays.

The voluntary carbon market has not taken off as earlier projected, however. It has had a $2 billion annual turnover at most and has contracted since 2021. Up to 90% of carbon credits now sold are based on “avoidance” of emissions (such as funding renewable energy, so less fossil fuels are used) rather than actually removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. But avoidance is always questionable as renewable energy may very well just add energy rather than replacing energy. Even clean cookstove projects, one of the most popular types of carbon-offset schemes, are probably overstating their beneficial impact on the climate by an average of 1,000%, according to a new study. You have probably heard about how most tree planting projects for climate compensation have failed in many different ways.

The mandatory emissions fees, such as the EU emission trading scheme are more effective even though there are some weaknesses. In order to reduce the harm to European manufacturers, the EU will from 2026 introduce a border tax on carbon, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism to ensure the carbon price of imports is equivalent to the carbon price of domestic production. It is a market instrument for sure, but as the total cap of emissions is set by the regulators it is not really a market in the traditional sense. To implement the system fully would, however, be mindboggling. Take the example of food products, where the EU applies the carbon tax to artificial fertilizer that are imported, but not to the embedded fertilizers in food products. Such an effort would entail an enormous bureaucracy even measured by EU standards.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that economic incentives and disincentives are powerful tools to change the behaviors of companies or individuals. If the local government charge more for the water, people will use less, it is quite simple – but it has nothing to do with markets or capitalism.

The transition from fossil fuels to renewables is to some extent driven by technological progress, e.g. a remarkable decrease in price for solar panels, which can be seen as a results of markets at work. But clearly the development of renewable energy has been driven by government support and subsidies combined with carbon taxes on fossil fuels. And still, the use of fossil fuels are increasing as the economy expand quicker than renewables replace fossil fuels.

Wolf inc

The market for biodiversity credits and ecological compensation are following in the footsteps of carbon trading with a lot of hype and expectations, but in the end most of them are flawed or without considerable effect. Apart from all the practical challenges, ecological compensation is based on two logical fallacies. The first is that one can construct ecosystems that have the same value as one that is destroyed, an idea that could only take root among pure technocrats. The second is that all the planet is already covered in ecosystems which means that you have to destroy or radically change an existing ecosystem in order to compensate for the loss of another ecosystem.

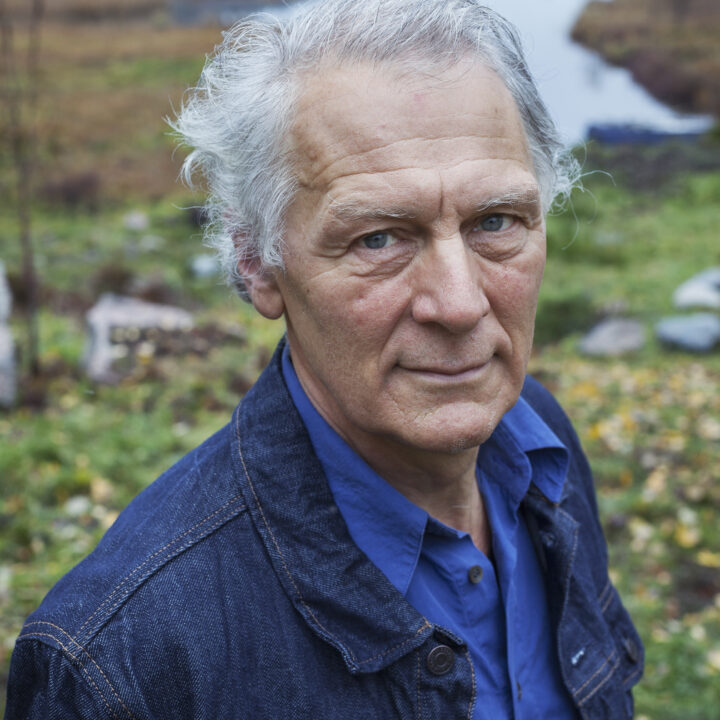

How do you compensate for a 300 year old oak tree? Photo: Gunnar Rundgren

There are no indications that markets for ecosystem services will be based on any of the scientific calculations that are now made to show the value of these services. This can be seen very well in the price for carbon credits, which has no relationship to the cost of climate change. One can also question the benefits of valuing ecosystem services in monetary terms, especially as the most valuable of these services have unlimited value and no known alternative. “It is a fantasy to believe that we can devise a rigged market system in which ‘corrected’ prices would tell the whole truth about the opportunity costs of everything in the world, and automatically optimize the scale of the economy relative to the ecosystem, as well as the allocation of resources within the economy” wrote Herman Daly, the creator of the concept of a steady-state economy.

A governmental inquiry on ecosystem services in Sweden concludes that economic valuation and compensation may, in many cases, not be the best way to maintain ecosystem services. It says that monetary valuation is not reliable or is completely unsuitable for complex situations that involve numerous ecosystem services, such as soil formation, water regulation and pollination. This, in a nutshell, is farming.

There will be increasing competition between the provision of food and the provision of ecosystem services. The commercialisation of farming led to the privatization of land, water, genetic resources and knowledge. A similar development can be expected when ecosystem services are going to be commercialized and external costs can be offset by measures on other places. Payments for ecosystem services leads to markets for ecosystem services which leads to privatization of ecosystems. We can today already see that rich people compensate for their carbon emissions by appropriation of poor people’s resources, e.g. by tree planting in Africa.

Surprisingly, there is not a very strong critique against the privatization that payment of ecosystem services actually entail, not even from normally anti-capitalist groups. Probably they don’t realize that payment of ecosystem services from taxes constitute a transformation of nature resources and commons into commodities.*

My main concern with market based solutions is the question of how they make us perceive nature. It seems that we increasingly confuse ‘value’ and monetary values. By framing nature into ecosystem services we reduce the meaning of all the other billion life forms and their relationships to be services for us. The more recently introduced term “nature based solutions” does little to help as it is all focussed around solutions to our problems, i.e. problems created by humanity. It is also quite nonsensical as there are no other “solutions” than those based in nature, where else could they be rooted?

The economy, aka capitalism, is governed by growth and competition. Therefore, the currently popular notion that businesses or the private sector will drive sustainability is delusional. It is highly unlikely that this economic system can be useful in a transition to a lagom society.

* We benefit from environmental payments on our farm. The payments are not transferable or tradeable and should rather be seen as economic incentives than as market based solutions.