You may have heard that planetary nutrient flows are completely out of whack. In fact, they’re so far out of whack that they threaten our survival as a species. Today, I’m going to talk about one way to address the nutrient flow problem that simultaneously makes our lives better and more resilient, with the Climate Corps providing the labor.

I’ll give my usual caveat: the solution I’m going to discuss is only one among many. There are no magic bullets. Also, this is a technical solution. The existence of a kick-ass technical solution does not change the fact that humanity’s biggest challenges are political.

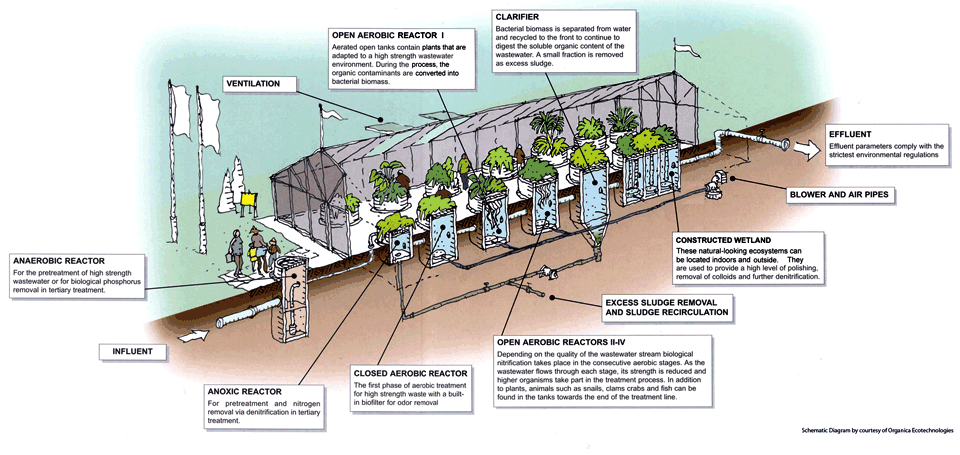

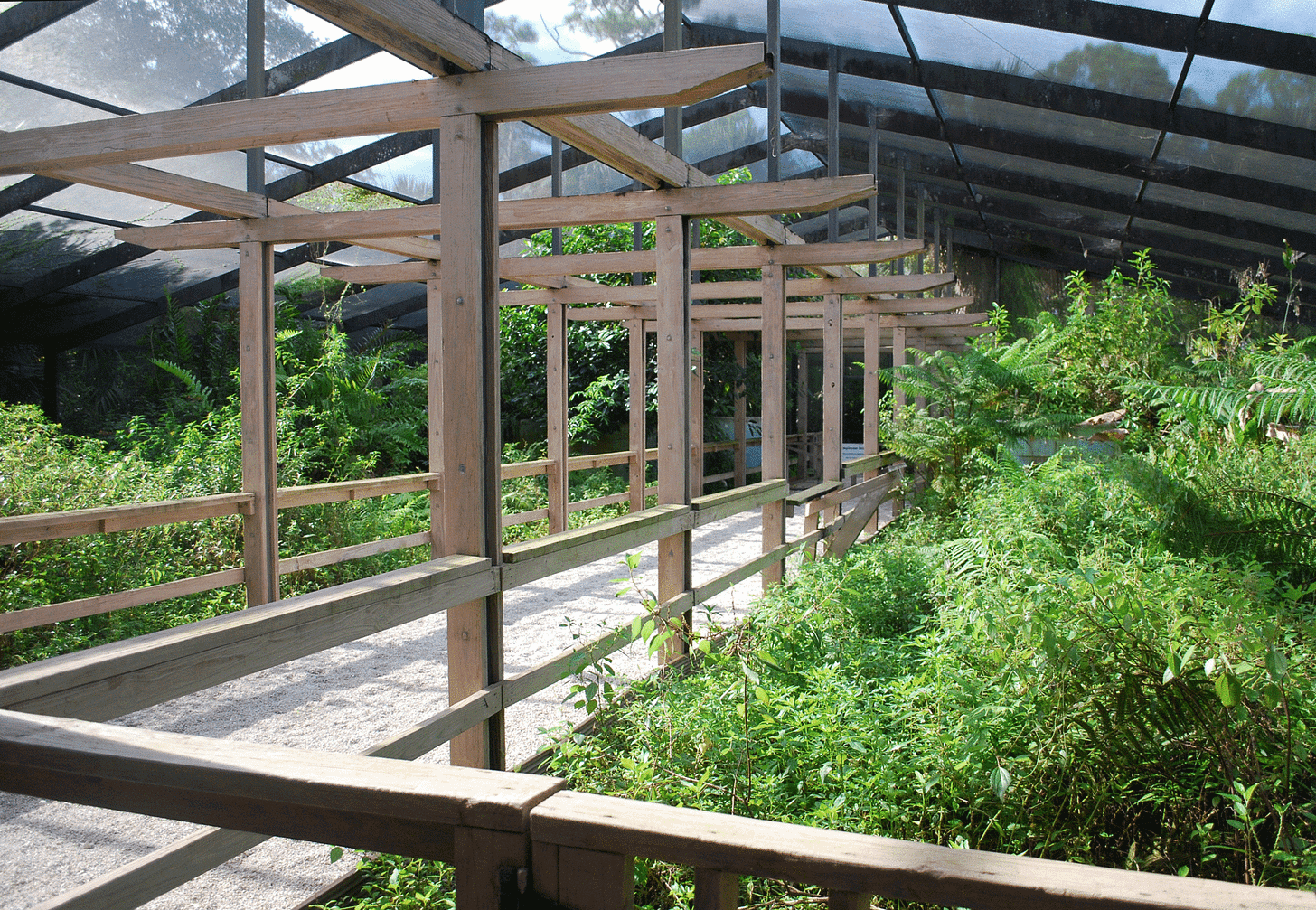

Okay, with that said, let’s talk about this super cool technical solution: living machines. Living machines are essentially intensive, indoor artificial wetlands. Technical names for living machines include “advanced ecologically engineered systems” and “fixed-film ecology wastewater treatment systems.” What they entail is mimicking natural processes of biological decomposition in a constructed aquatic environment.

Simply put: dirty water goes in, passes through a series of self-contained aquatic ecosystems, and clean water comes out. The water is, in fact, so clean that it can be safely discharged into sensitive aquatic environments, like natural wetlands. And it does all of this without any of the usual chemical treatments or high-energy inputs of conventional wastewater treatment.

Living machines produce such safe effluent because they achieve what is known as “tertiary treatment,” meaning they successfully abate pollutants. How does a biological system do this? Simple: it uses them as inputs.

Let me explain. The most common such pollutants are nitrogen and phosphorous. These happen to be the two nutrients whose out-of-whack flows have pushed us past a key planetary boundary. The biggest reason for this is industrial agriculture: it relies on synthetic nitrogen and mined phosphorous to exceed the carrying capacity of the ecosystems in which it operates.

One of the big problems with industrial agriculture is that a great deal of the nitrogen and phosphorous applied isn’t actually utilized by the food being produced: most of it runs off into waterways. This leads to far-reaching, ecologically catastrophic events (“eutrophication”).

By constructing a complete food chain within the living machine, each step creates the food for the next step. Excess nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorous, feed microorganisms which are then consumed by larger creatures and so on up the food chain, until we are left with harmless components and a great deal of life. The living machine converts pollution into biodiversity and clean water, instead of run-off and eutrophication. It’s a prime example of true “regeneration.”

There are two primary configurations for living machines: inline and floating. An inline system is what you’d use for sewage or anything else where there’s a continuous flow, with pumps moving the wastewater back and forth through the system, mimicking a tidal flow. A floating system sits atop an idle body of water like a pond or a lake and passively floats around via wind to clean water as it goes.

At this point, you might be wondering if living machines are a fringe hippie fantasy, and the answer is no. Quite a few of them are in operation, successfully cleaning wastewater on college campuses, villages, highway rest stops, military bases, office buildings, visitor centers, and poultry processing plants. They work, extremely well.

If there’s a major criticism to be made of living machines, it’s that they mostly don’t produce things people can use; they just discharge the treated water and call it a day. But this is a function of regulation, which requires that treated wastewater—even if it’s of drinking water quality—be handled as though it were toxic waste. So that’s not a limitation of living machines but of the regulatory environment in which they operate.

The inventor of the living machine, a marine biologist and original New Alchemist named John Todd, envisioned them as a means of recycling nutrients in a closed-loop economy: they would produce food, fiber, etc. (Finding few takers for his vision, Todd became a somewhat reluctant entrepreneur and launched a successful company building living machines; there are now quite a few companies building variations on his design under different names.) The closed-loop version of the living machine is still very much possible, but regulations and economic incentives would have to change. It is currently much cheaper and easier to exploit nature and burn fossil fuels than it is to recycle anything, much less contaminated wastewater.

But for our purposes, it’s worth envisioning what it could look like to bring humanity back across the planetary boundary for nutrient flows with the help of living machines, and how a Climate Corps could make that possible.

The most obvious direction to go in with inline systems would be the production of carbon-sequestering biomass. A living machine discharging into a field of willow, for instance, would turn wastewater into fencing, outdoor structures, furniture, baskets, dye, and more. Those items would then sequester 50% of their weight in carbon for the duration of their lifespans.

Floating systems, used to remediate contaminated bodies of water, would both bring vital riparian areas back into ecological service once their work is complete and then offer the opportunity for the production of edible aquatic plants like wild rice, duck potatoes, pickerelweed, and much more. One can even imagine building a series of living machines in the form of chinampas, which could shift into agricultural production once their remediation work is finished.

A very ambitious Climate Corps would be needed to make this a reality. The scale of the task is immense: think of all the wastewater systems that currently devour energy and chemicals to produce subpar effluent. And think of all the people—46% of the world’s population—who aren’t served by any kind of sewage system at all. Then add on to that all of the contaminated bodies of water that can and should be remediated. We’re talking about a multi-generation project here, and one that would require a huge amount of relatively skilled labor.

Fortunately, the world is filled with people who would love to do meaningful work to give humanity a future on this planet. There are millions upon millions of engineers currently working in extractive industries whose skills will be needed. Creating a global Climate Corps that can make use of them to build living machines is one path out of our current predicament.

It bears mentioning that almost any contemporary technology will require further innovation to be suited to a low energy society. In the case of living machines, that will mean figuring out how to build and operate them with as few inputs as possible: minimal electricity, manual construction, no synthetic materials. It’s not hard to imagine how this might be done (bentonite clay, mechanical wind turbines, shovels, etc), rather than dump trucks, plastics, and grid electricity.

But that is nonetheless work that must happen. And if you’re not interested in waiting around for a global Climate Corps to take shape, it’s work you can start doing today.