I don’t know quite what the Olympics are to me. Recently I said to a friend that they’re my grief circle — a place where I can sit and express the full range of emotions, from the joy of transcendence to the heartbreak of loss. That’s not quite true, of course, because there are emotions I’m still avoiding — and I’m still not ready to be witnessed. But it’s a start. And yes, the Olympic Games do provide a perfect distraction from the world’s urgent challenges and immense suffering — and yes, I needed that break. After two weeks of pure emotional release, I feel refreshed and newly inspired by the spirit of human collaboration and achievement — the ways we can push each other to new limits while uplifting each other with awe.

After the men’s 100m final, Rebecca Solnit wrote:

How are the Olympics not scarcity economics? A bunch of extraordinarily talented people show up, but only one of them will get the gold and the press will make it seem like even getting silver is sad loserdom. Horrified to see a Romanian gymnast get and then lose the bronze when the scores were recalibrated; happier for victories for smaller countries with fewer athletes and resources. But that men’s 100 in which all eight men basically arrived at the finish line as a pack — to some of us a few inches or feet are meaningless.

I once told a man I that I am very active and not at all athletic — after miserable PE in jr. high (and skipping high school), I love moving — I row, swim, do yoga, hike, run, etc. — and hate competing and also the jeering, raucous voices of people yelling during sports and the whole vibe and hierarchy. I think of my friend Úlfur who as a child said that if the other boy wanted the soccer ball so badly why shouldn’t he let him have it? The great secret of life is that it runs far more by cooperation than competition. Will continue not watching the Olympics, and I’m in New Mexico watching clouds with ardor. Which are not competing.

It’s a fair point, if you take that particular race as representative of the Games as a whole. What I’ve seen, though — particularly among women’s events — is athletes reaching heights they never dreamed of and falling even more deeply in love with their sport, by being pushed and inspired by their competitors.

We saw it when Simone Biles and Jordan Chiles bowed down to Rebeca Andrade during that iconic moment — which was also the first time three Black athletes stepped up to the gymnastics podium.

We saw it, too, when American climber Brooke Raboutou gazed up, smiling widely and with tears streaming down her face, as Slovenia’s Janja Garnbret bumped her from the gold medal position in a truly incredible display of strength and skill. Afterwards, Raboutou ran up to Garnbret for a huge hug.

There have been countless moments like this during the last two weeks, showing what can be achieved when competition happens within an overall collaborative framework — like we see happening in nature, where competition exists within an integral symbiosis.

It’s no coincidence that this is also the first Olympic Games with gender parity in athlete numbers— though of course this spirit of cooperation is evident in men’s as well as women’s events. I like to think that the strides being taken in women’s sport and the destigmatization of conversations around mental health have had a positive impact on the Games as a whole. Plus, as Slow Factory have pointed out, the Games are “a portal of opportunity for many people across the Global South. Olympians have the opportunity to create new lives for themselves and inspire their communities.”

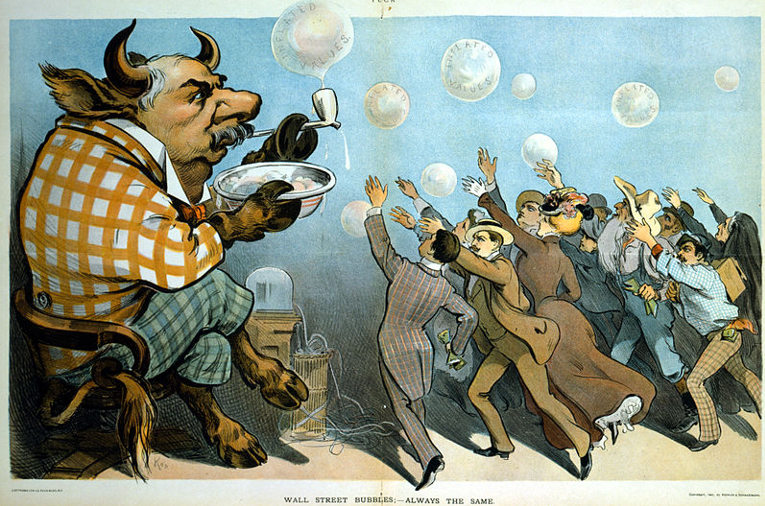

All that said, there is plenty about the Olympics we will have to leave behind. A long-standing policy of ‘social cleansing’, which, in Paris in the lead-up to the Games, saw people seeking asylum and those experiencing homelessness bussed out of town with the ‘encouragement’ of armed police; the hijab ban that forced French female Muslim athletes to withdraw from the competition; the wave of transphobic misinformation about Tunisian boxer Imane Khelif; the fact that some athletes, despite medaling, cannot afford to practice their sport full-time; the exclusive nature of some sports, such as hockey, rowing, and equestrian events, whose teams do not represent the diversity of the countries they represent. That’s not to mention the poor triathletes who had to swim in the filthy, e. coli infested Seine. All of these serious issues are connected: the Olympics exists in a hyper-capitalist, white supremacist system, founded on injustice and exploitation, where success is judged not by human or environmental wellbeing, but by the maximization of profit — which is itself enabled by racist othering and the construction of false binaries.

The Olympics is in a kind of crisis. Cities no longer want to host the Games. Residents increasingly recognize that it’s a bad deal. This is just another sign among many that the dominant socio-economic system is working for fewer and fewer people (for Indigenous populations and the Global South, it arguably never ‘worked’ at all). The Paris Olympic Games cost just under €10 billion. The International Olympics Committee is a not-for-profit organization that redistributes 90% of its profits, primarily to support sports development worldwide, as well as to host nations, which rarely make a profit themselves. (Paris may be an exception, but in order to make a profit ticket prices have been eye-wateringly high, compounding the Games’ exclusivity.) So who profits in the end? What might the Games look like if the entire ecosystem were not-for-profit, running in the interests of the athletes, the host communities, the environment, and spectators?

Processing these simultaneous truths — inspiration on the one hand, and systemic injustice on the other — feels like a microcosm for our wider dilemma. As we co-create a new/old system, a pluriverse of alternatives, what do we want to keep — and what will we leave behind? What might a post-growth Olympic Games look like?