Hurried pursuit of a liquefied natural gas windfall in B.C. and Alberta will squander a key component of Canada’s long-term energy security while causing environmental devastation, according to a new report.

Scaling up LNG exports from fracking in the Montney basin that straddles the two provinces almost certainly will jeopardize local water resources, species habitat and the country’s struggling effort to meet climate targets.

And there could be another cost down the road:

“The current policy of exploiting the Montney as fast as possible for LNG exports may create risks that gas will be unavailable for other uses in the future.”

This, according to energy analyst David Hughes, author of a comprehensive report called “Drilling into the Montney,” released June 24 by the David Suzuki Foundation.

“The Montney represents Canada’s largest remaining accessible gas resource and is forecast to provide a significant portion of future gas production with or without LNG,” Hughes told The Tyee. “Conventional production from mature gas fields in Canada has declined sharply over the past couple of decades.”

“Production has been made up by unconventional plays like the Montney which can only be accessed with the technology of hydraulic fracking and horizontal drilling. And those technologies come with significant environmental impacts in terms of climate change, water consumption, biodiversity loss and land disturbance.”

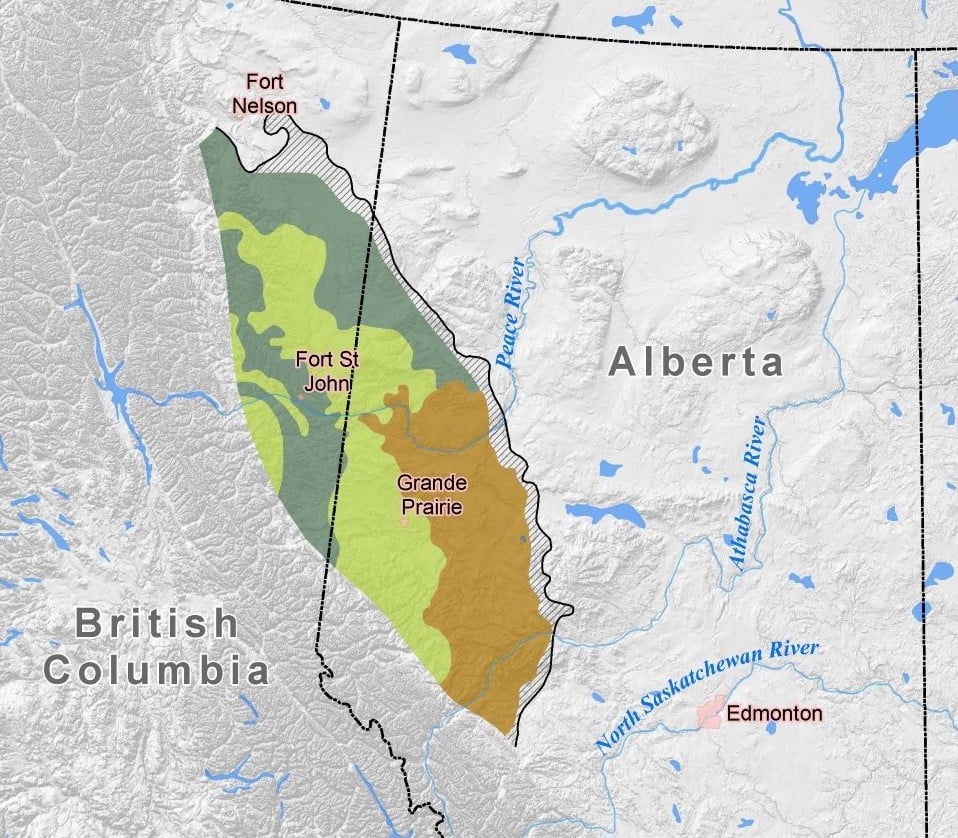

The Montney basin is an oval-shaped, 96,000-square-kilometre geological formation that stretches on a southeast diagonal from Fort Nelson, B.C., at its top and includes the territories of Treaty 8 First Nations. The Montney currently produces 10 billion cubic feet of methane per day or roughly half of Canada’s total.

The Montney basin straddles the border between BC and Alberta. Map via Wikimedia, Creative Commons licensed.

Hydraulic fracking, unlike conventional methane drilling, requires costly high energy inputs to drive a brute force technology that cracks open deep rock with highly pressurized blasts of water, toxic chemicals and sand.

After drilling hundreds or thousands of metres vertically into a targeted zone, a fracked well will then follow the target zone with horizontal laterals for two to five kilometres underground.

Tons of a sand-based material called proppant is then injected into these horizontal laterals to keep rock fractures open so gas or liquids (such as highly valued condensate) trapped in the earth can flow into the well.

The technology is so forceful that it has changed seismic patterns in the region and caused significant home-rattling earthquakes in both B.C. and Alberta.

“But without this technology Canada’s gas production would be declining,” noted Hughes.

A vast maw for water and sand

Based on detailed industry drilling data, Hughes calculated that the Montney now consumes 21.7 billion litres of water a year in a region already hit by drought and wildfires accelerated by climate change.

That amount of water is equivalent to the entire flow of the Bow River at Calgary for two days, said Hughes, or enough water to quench the thirst of seven billion humans for one day at three litres per person.

Of that 21 billion litres, nine billion are directly consumed in the B.C. portion of the basin. Future LNG exports could increase that Montney water demand to 35 billion litres a year.

Industry says it currently recycles about 50 per cent of the wastewater it produces.

On average a fracked Montney well now consumes about 23.1 million litres, a 10-fold increase since the industry first started applying hydraulic fracturing nearly 20 years ago.

The industry’s growing need for water mirrors trends in several big shale basins south of the border. Fracked wells in Texas, for example, now use as much as 151 million litres of water. The New York Times recently estimated that the U.S. fracking industry has devoured 1.5 trillion gallons of water since 2011.

That’s the same volume used by tap water consumers in Texas for an entire year.

Surging fracking in the Montney also demands more use of high-quality sand, often mined as far as away as Wisconsin and imported by truck or train. The mining of sand for proppant imposes its own environment costs, including air pollution and groundwater contamination and depletion.

An average fracked well in the Montney now consumes 5,324 tonnes of proppant, a fourfold increase since 2010. This volume of silica, which comes in a variety of sizes, requires, per well, 245 loads with large sand haulers that mostly run on diesel fuel.

One tonne of sand can cover an area of approximately seven square metres at a depth of 10 centimetres. Fracking in the entire Montney devoured five million tonnes of sand last year, amounting to 229,387 truckloads and more than half of all fracking sand used in Canada.

A call to conserve gas for the future

In B.C., fracking has increased methane gas production by 136 per cent since 2005, with the majority of it now extracted from a 39,000-kilometre area centred on Dawson Creek, B.C.

The most productive portions of the Montney lie in B.C. for geological reasons. Alberta spends more energy, water and sand to get less methane from the basin than do B.C. operations.

“There are sweet spots,” said Hughes. “When you look at the data in detail you can see really good wells are relatively scarce and that a lot of gas is coming from lower-productivity wells.”

Hughes calls the Montney “a strategic non-renewable resource” that should be treated as an essential bank for the country’s energy security. According to the Canada Energy Regulator, or CER, the basin will provide between 58 per cent and 63 per cent of all Canadian gas production over the 2024-50 period and will be the primary source for LNG exports.

“Selling it off as fast as possible to foreign markets for short-term gain compromises Canada’s ability to meet climate targets and future energy security and is therefore extremely unwise,” Hughes said.

From ‘Drilling into the Montney’ by David Hughes.

Just five companies control more than 65 per cent of production in the Montney: Ovintiv, ARC, Tourmaline, Canadian Natural and Petronas. Companies such as Ovintiv boast that provincial royalty percentages are “significantly below average [of] U.S. basins.”

If all six LNG projects currently on the books are built, they would require a gas supply of 6.7 billion cubic feet per day to make their shipments.

That is equivalent to all of British Columbia’s or one-third of Canada’s current production.

The Montney would supply most of this methane because of proximity to the coast.

Climate target numbers fail to add up

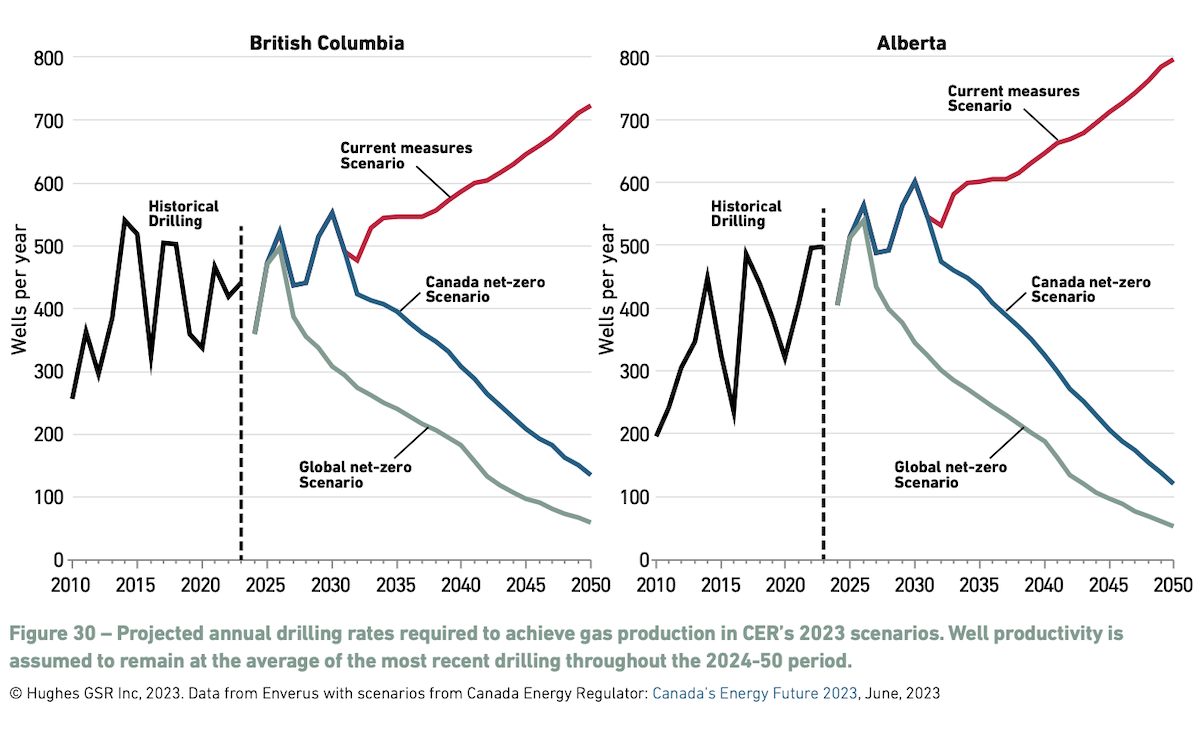

The Canada Energy Regulator recently offered three possible pathways for future energy production in Canada in its report “Canada’s Energy Future 2023,” two of which meet Canada’s legislated net-zero carbon target.

In one scenario, Canada and the world actually accomplish this difficult goal. In another, Canada achieves net zero, but the world doesn’t. And in a third scenario, Canada sticks with existing policies and reduces emissions only 16 per cent from 2022 levels by 2050, guaranteeing accelerating climate disorder.

Only in the third scenario, where Canada fails to meet its net-zero commitment, would there be enough gas production to supply all six LNG projects. This would require drilling more than 32,000 wells over the 2024-50 period, increasing water consumption by 62 per cent to 35 billion litres annually and chewing up land equivalent to nearly six city of Vancouver footprints.

In the CER scenario where Canada and the world reach net zero, the LNG Canada Phase 1 and Woodfibre LNG projects that are currently under construction would have to reduce output by 90 per cent in 2045, 20 years before their designed lifetime. Zero gas would be available for other LNG projects. This scenario would still require more than 12,000 new Montney wells by 2050 to meet LNG export and other requirements.

Hughes calculates that the six under-construction and proposed LNG projects would add 10 megatonnes of annual heat-trapping carbon emissions from upstream drilling, fracking, processing and transport — assuming the government is right that emissions intensity can be reduced significantly along the way. That amounts to 16 per cent of British Columbia’s current emissions at a time when both Canada and British Columbia claim they are committed to net-zero emissions by 2050.

As a result, Hughes concludes that approved and proposed LNG plants “will deplete the most economic portions of the basin, ramp up the environmental impacts and make it extremely difficult if not impossible for the country to meet its net-zero carbon targets by 2050.”

Hughes based his report on production data from 16,848 existing wells in the Montney within the commercial database compiled by the Texas company Enverus from government sources.

Hughes, who lives on Cortes Island in B.C., remains one of the country’s top energy analysts. As an earth scientist he has studied the energy resources of Canada and the United States for more than four decades, including 32 years with the Geological Survey of Canada, where he researched unconventional energy resources. ![]()