Jon Alexander, who wrote the book Citizens back in 2022, has been on a bit of a quest this year. As a result of the book, he has been around the world talking to citizens—usually activist citizens—“from Grimsby to Auckland and back again”, as he puts it.

What he learnt from talking to citizens, as he explains in the introductory article, is:

that people everywhere across the world — literally everywhere — are finding one another, organising together, and stepping into whatever power they have to shape the future for the better. I’ve seen incontrovertible evidence that there is something very powerful and positive wanting to take shape in this time.

Gloomy all the way down

Yet at the start of the year, he realised that this wasn’t what the discourse was like at the moment. Instead, it was gloomy all the way down:

the headlines of our time tell the story of a gathering darkness. Our crises are intensifying. Autocrats, authoritarians, and outright fascists are on the rise.

As you can imagine, this has produced a powerful sense of dissonance. His explanation is that the citizens are still organising under the radar, in the shadows, whereas authoritarians are very visible everywhere. The citizens are still what futurists would call a weak signal of change:

in a time when pessimism is growing, I feel genuinely, authentically hopeful, rooted in what I know is happening. It’s the kind of hope Rebecca Solnit describes in her beautiful book Hope In The Dark as distinct from and “an alternative to the certainty” of both optimism and pessimism.

Nightmare versions

And so he has been writing a succession of posts on his Medium site that are intended to draw some lessons from what he’s seen, positive and negative. Writing is thinking, as they say. Fortunately he’s kept them outside of Medium’s paywall.

In the rest of this post, I’m going to try to capture some of the highlights from this series, while recommending that it is worth having a look at the articles themselves.

It is a bit of a world tour: Argentina, Poland, Wales, Taiwan. He starts in last year’s election in Argentina of the far-right Javier Millei because it is the nightmare version of authoritarianism. He points out that the final run-off—in a climate of economic calamity and financial desperation—was between the chainsaw wielding Javier Millei and Sergio Massa, the finance minister in the previous government:

Stick or twist, when you’re desperate and feel you have pretty much nothing left to lose.

Context always matters

The Polish election, at about the same time, looked like it might be heading the same way. The right-wing Law and Justice Party was leading in the polls. But to general surprise, a coalition of centre and left parties, under the very establishment Donald Tusk, won a majority. One of the things this tells us is that context always matters in politics.

But what happened in Poland was that civil society organisations made the difference,

mobilising in recognition of the danger — on climate action, labour rights, and especially women’s rights — in a way that did not happen in Argentina… Civil society organisations used their communications efforts to raise the stakes in the campaign, and in doing so drove a huge increase both in overall turnout, and especially in turnout among women and young people.

This video, shared by Alexander in his piece, is a compelling example of how this worked:

‘Time can still be bought’

He draws two lessons from all of this. One, from Argentina, that we need to acknowledge that our political systems are failing: if we pretend they are not we play into the hands of the ‘anti-political’ solutions of the authoritarians. Two, from Poland, that “time can still be bought”.

But there are limits to this. Poland isn’t, yet, “authentic hope”. It is only a space for hope.

In the third of these essays, he draws on the work of the Turkish writer Ece Temelkuran—new to me—and her 2022 book Together to go further into the idea of hope. Her earlier book on Turkey documented Erdogan’s path to authoritarianism:

It is an intensely powerful diagnosis of the path to authoritarian chaos we were and are all on, not just Turkey; Temelkuran’s essential insight is that we are simply at different stages in the process.

Sensible, Grown-Up Politicians

Together was a response to that, but also a response to a question she kept being asked about where to find hope:

I fantasised about handing the next person who dared ask me the question a menu for Restaurant Hope. I pictured a quaint brasserie serving a main course of Back To Our Senses Stew. Diners would be offered a bowl of Democracy served in a rich sauce of Sensible, Grown Up Politicians, with all the Global Turmoil evaporated off.

And heaven knows we have a lot of Sensible Grown-Up Politicians around the place. Albanese in Australia, Starmer in the UK. But: because they have not yet realised, or acknowledged, that our political systems are failing, they don’t have the tools to deal with authoritarianism.

The failure of the consumer story

But it’s not just down to them. We can’t sit down in Restaurant Hope and wait for the menu. We need to be in the kitchen.

This takes him back to an argument he made in Citizens that this is about competing stories. Part of the failure of our political systems is also down to a failure of the consumer story.

The Consumer Story holds that our role as individuals is to pursue self interest, choosing the best option for us from those that are offered… The most dangerous implication of the Consumer Story is that we can expect no better of each other than this.

Authoritarians offer to replace this with a story about being a subject: if we put them in power, they will fix things for us (although they don’t, of course).

A story about citizens

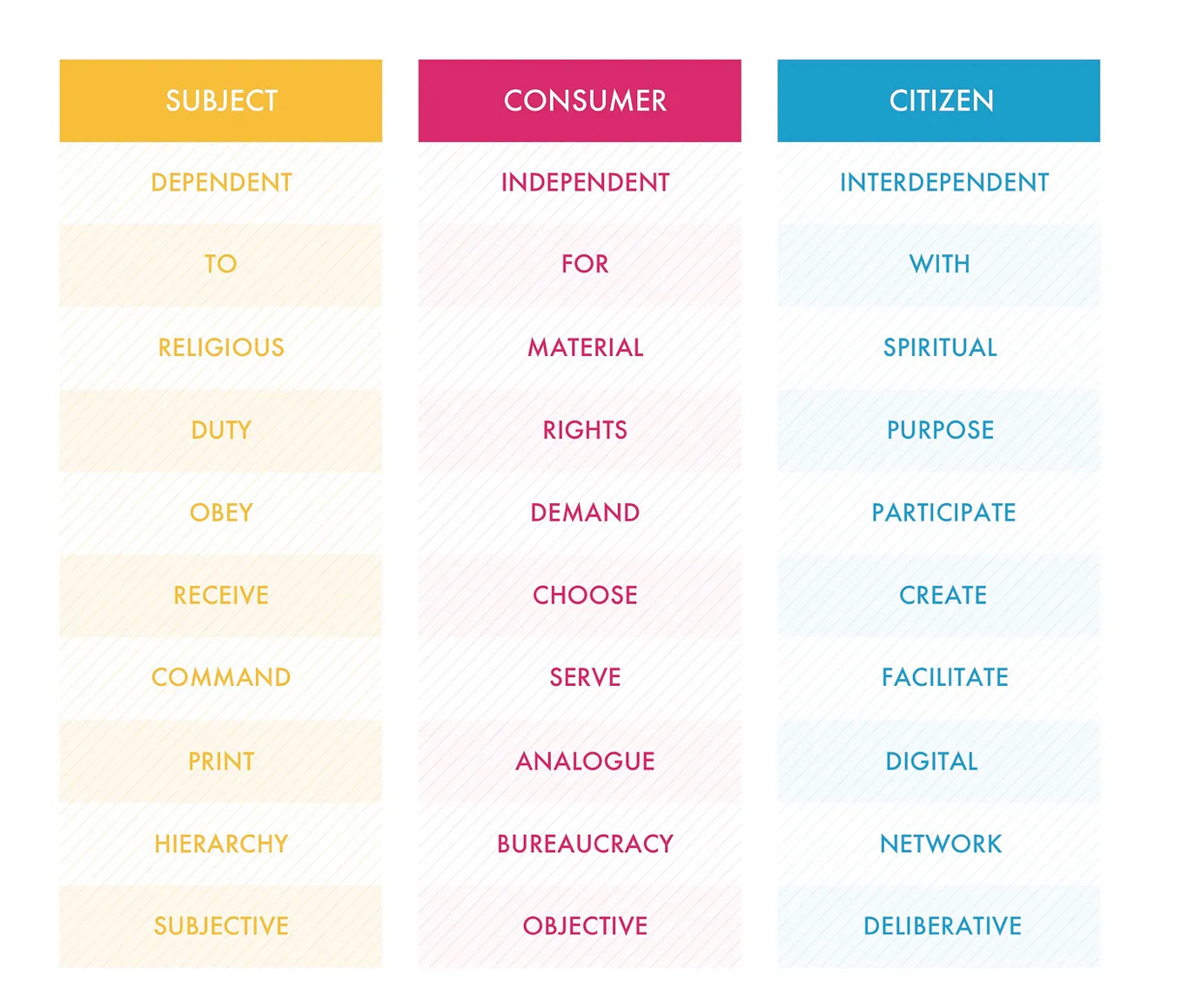

Alexander proposes instead a story about citizens, and has a diagram from his book (I’ve shared this here before when I wrote about his thinking in Citizens three years ago.)

(Source: Jon Alexander)

The Citizen Story holds that all of us are smarter than any of us. It holds that we the people should neither do as we are told nor pursue our individual self interest, but instead contribute our ideas, energy and resources to the pursuit of the best outcomes for society as a whole. Our role is not just to choose between options, but to shape what they are.

Believing in people

In here, somewhere, is also a story about trust, and how to rebuild it:

This has to mean, as Taiwanese Digital Minster Audrey Tang insisted in the interview for my book, with government trusting people — not just imploring people to trust government.1

We need to believe in people if we, the people, are to have any hope for ourselves and for humanity. This piece is already too long, so I’m going to end with part of another quote in the same vein from Ece Temelkuran’s book Together:

To love other humans is not a broken hearts club; it is a philosophical and political responsibility that should be worked on with all the faculties of the mind, sometimes pushing our mental and emotional skills to the limit. fainthearted. It is the most serious invitation to challenge the bloody history of humankind.