My adult life has run on two diverging tracks. On one, I played science. The other track branched off at age 34—twenty years ago this month—when I started teaching a class on Energy and the Environment. I was eager to piece together our likely energy future: how we would beat climate change and leave fossil fuels in the dust. Against my wishes, this fork presented unexpected turns that took a long time to sink in. The two tracks eventually became too divergent to keep a foot on each. At this stage, I can’t seem to muster the denial it would take to disregard what I have learned so that I might return to the more blissful play-time track.

Much of my writing in the last few years has tried to capture why I have become convinced that modernity can’t last, likely to begin disintegrating in the near-term. In this post, I attempt to distill core elements informing this sense. My apologies if this seems like a rehash. For what it’s worth, the packaging exercise is something that helps me address the question I constantly ask myself: what part of this might I have wrong? It’s a way to take stock.

Growth

I began the Do the Math blog with a pair of posts about why growth can’t last—hitting limits in a historically short time. I also dedicate the first chapters of my textbook to the same topic. In 2022, I synthesized the arguments in an academic paper. This thread should be very familiar by now to my readers, and in fact really ought to be common knowledge. Yet, modernity still operates in a market economy and political system built around a growth expectation. Pension plans and social safety nets (like Social Security and Medicare) become Ponzi schemes unquestionably destined to fail at some point as growth falters.

Strike one against modernity. Rookie mistake. Pursuit of growth won’t end well, although it will not be abandoned without a fight—taking place this century, I would guess.

This awareness led me early on to embrace the pleasant notion of steady state economics as a helpful illusion to alleviate the worry. But I had much to learn, still.

Energy

The primary focus in my early years of exploration was energy. To a physicist, this was familiar territory. Moreover, as an experimentalist (basically a sub-par engineer of every stripe), I could evaluate practical pros and cons of implementation, and even cobble together my own off-grid home experiments. I operated under the all-too-common but naive assumption that technology and cleverness can solve essentially any problem.

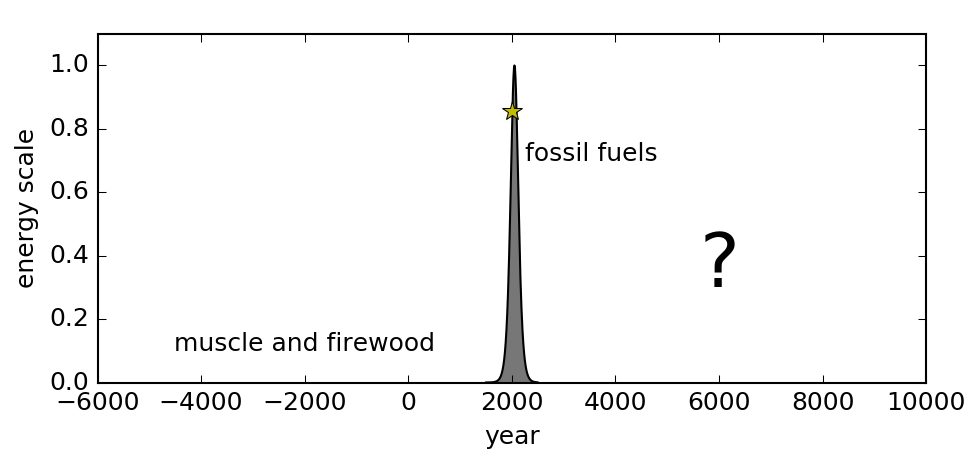

I began with an awareness that modernity was made possible by a one-time rapid expenditure of fossil fuels, and that these would disappear about as quickly as they appeared, leaving us in a precarious position: uncharted waters for modernity.

Initially, I was wowed by the overwhelming scale of solar input: four orders-of-magnitude more than what we currently use! Delivered free for billions of years. Nothing else comes even close. It seemed so obvious. Case closed. I can still access the feelings of reassurance I had in those optimistic days. This is how life is when operating within narrow boundaries: straightforward. It’s related to why computers excel at games where the rules and parameter space are well-defined and bounded. Narrow the scope until—viola—a solution!

I was, of course, aware that storage was the main technical problem. But if storage could be solved on seasonal time scales, solar could work practically anywhere in the world (e.g., by banking summer input for use in winter). Solar-to-liquid (artificial photosynthesis) was an especially appealing notion. In any case, the fact that I had a working off-grid solar operation at home put this avenue so firmly “onto the real axis” that fusion hopes seemed quite unnecessary and fraught, by comparison.

What I had not fully considered yet was that:

- Electricity is not obviously able to satisfy modernity’s demands in agricultural, manufacturing, and transportation domains.

- The ecologically-destructive materials treadmill required by diffuse forms of energy would never be renewable/sustainable.

- Most importantly: what we use energy to do on this planet is itself fundamentally unsustainable. A “win” in technology/energy is a loss for life and humanity.

I eventually developed some awareness of the first point via my Alternative Energy Matrix and had glimmers of the second point in my evaluation of a battery large enough to satisfy demand. The third was still off my radar.

Can we kick the can down the road for some time longer using technology? Yes. But at what ultimate cost, and to what end?

Materials

It is obvious enough that we process a lot of stuff to run modernity, and that this comes from somewhere (mining) and goes somewhere (waste, pollution). But the earth is large, yeah? The limits hit home for me in 2012 when I visited the long-closed Kennecott copper mine in the remote Wrangell mountains of Alaska—still remote today. One hundred years ago it was far more so. The fact that they even found this copper deposit, that it was worth building a dedicated railroad (with trestle bridges) across rugged terrain, and that it was depleted of high-grade ore over several decades of operation all told me that this planet has been well-scoured for the low-hanging fruit. Indeed, mines once exploited ore concentrations of 5% or better, but now must settle for 0.5% or lower (and ever-diminishing).

The copper demand alone for building enough solar panels just to maintain steady-state replacement in a full-scale solar deployment would rival present-day global copper extraction indefinitely. Recycling can reduce new mining (once initial build-out is done), but never eliminate it. Thus, the ground assault—and associated ecological damage and biodiversity loss—must actually ramp up to support alternative energies (see Table 10.4 in this DoE report), and doesn’t let up.

Recycling is also a long-term disappointment. At typical recovery rates, only a few cycles are possible before debilitating depletion is achieved. Even unheard-of 90% recovery is down to half the original resource in only 7 cycles, and down to 10% in 22 cycles. Recycling is not a get-out-of-jail-free card. A “circular economy” in the context of modernity is another empty fantasy. Biological/ecological systems manage something like it, but involving a completely different set of materials and context—worked out over billions of years of tuning by lots of trial and lots of error.

We can recycle (and then kick) the can down the road for a while, sure. But at what ultimate cost, and to what end? Modernity will eventually become materials-starved, ruining many environments on the road to nowhere.

Timescale

This brings us to a key insight that we are surprisingly, shockingly ill-equipped to grasp. Our lives are inconsequentially fleeting compared to relevant timescales, so that our lens on life is grossly distorted to the detriment of our species and others. Evolution has operated over billions of years—about 50 million human lifetimes—to produce current biodiversity. Humans have been on the planet for 30,000 lifetimes. Our own species has been around for 3,000 lifetimes. All of recorded human history only spans 70 lifetimes. What most people associate with modernity (post-Enlightenment) is just 5 lifetimes, tops. Even much of this modern period seems distant and obsolete to many: an exceedingly short-sighted view. Compounding matters, market economies focus on timescales far shorter than a lifetime, so that the mismatch becomes even more extreme and glaring.

Why does this matter? It’s almost the whole story! Grasping the flash in time that modernity represents prepares the brain to recognize that flashes are usually exactly that, rather than the beginning of a new normal. This argument in itself certainly is not conclusive, but as soon as one makes the—you know—neural connections to other contextual elements in this post (some yet to come), arguing otherwise puts one on very thin ice.

Ecological Health

I frequently point out that humans and our domesticated animals constitute 96% of mammal mass on the planet, leaving a rapidly-diminishing sliver for wild mammals. Most striking to me is that only 2.5 kg of wild land mammal mass remains for each person on the planet: it’s almost gone, and soon will be at the current rate of attrition. In my lifetime, the average decline in vertebrate populations is an alarming 70%. A sixth mass extinction appears to be underway, with vastly more populations in decline than are increasing, and extinction rates about a thousand times over background rates—climbing fast. Like the boiling frog, we are calmly witnessing ecological doom as our normal backdrop, awaiting the next iPhone model (the two phenomena are not disconnected).

Modernity has supplied the temporary illusion—initiated by our foray into agriculture—that humans stand alone and apart from the community of life on this planet. Our narratives around evolution, even, have emphasized the survival of the fittest rather than complex interdependencies and mutual cooperation in a co-dependent web of life. We imagine ourselves as the victors in the game. Winning, in this sense, is the quickest path to losing—because it’s not a competition.

I find that this argument often falls on deaf ears, as our culture has lost basic ecological awareness—fed by grocery stores and living in sterilized boxes. We have lost the understanding that WE (all life) are all in this together, and succeed or fail as a community. The fact that modernity is a short-lived stunt based on rapid depletion of non-renewable stocks (even arable land, in practice) is somehow not obvious to most. In our typical narrow-boundary analysis, it feels like we’ve finally figured it all out. If we manage to shut out the facts that:

- growth can’t continue,

- modernity has always been utterly dependent on a one-time stock of fossil fuels,

- the low-hanging fruit of materials has been exhausted,

- “renewable” energy is still completely dependent on diminishing non-renewable materials,

- that it has all happened in a blinding flash (fireworks show), and

- all at tremendous cost to the web of life,

then I suppose the limited view that remains looks pretty great. It just leaves out too much for me to go along.

Evolution

One of my more recent revelations ties a number of these elements together. We got where we are (as human organisms) by no other mechanism than evolution, which operates on many levels at once in a tangle of ecological relationships forever beyond our understanding. Success and failure slowly operate over millions and billions of years to shape a dynamic equilibrium in something that approximates wisdom.

We owe everything to this heritage. Let’s keep the hierarchy straight: universe; habitable planet; evolved life; ecological community; our species; our constructs (like the economy). Each owes its existence to the preceding entry. Operating under an inverted presumption (e.g., most college curricula) is a recipe for disaster: it’s a fiction that can’t sustain itself.

Thus, any species that gets out of step with the rest of the community of life (either biologically or via its constructs) will fail by the dispassionate judgment of evolution. It might take a while to be fully expressed: even a hundred human lifetimes is quick on evolution’s pace. The degree of destruction to biodiversity and ecological health inflicted by modernity won’t fail to provoke a proportional response, which will bite hard when communities of life fail and our own survival is imperiled.

Counterfactual Context

Our cultural tendency is to focus on one detail at a time by deliberately removing messy contextual links so that we may scrutinize the internal logic of each piece in isolation (see Iain McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary for insights into this phenomenon). I’m sure any of the previous sections could be made to seem less scary/dire in such a piecemeal way by intentionally ignoring the full context. But guess what: the actual real biophysical world we live in does not operate as tidy, isolated, non-interacting domains—rendering invalid many of our analysis efforts, however elegant.

When holding all the factors together, in relation to each other, it is exceedingly difficult to argue that modernity is at all likely to succeed. In order to contrast our actual situation with the sorts of contextual inputs that would offer convincing—but counterfactual—evidence that modernity has a decent chance of sustaining itself, consider the following list of statements in an alternate universe:

- Versions of modernity have succeeded numerous times in the universe, as evidenced by advanced alien civilizations almost everywhere we look.

- Modernity has been around on our planet for millions of years, so that life on Earth is fully adapted and compatible in an evolutionary sense.

- Modernity is not reliant on non-renewable energy sources, and has not been so for tens of thousands of years.

- Modernity hasn’t needed to mine new materials from geological deposits for countless millennia.

- Biodiversity is holding steady: with population increases balancing decreases; and extinctions consistent with background rates.

- Forest cover, fresh water, habitat, are all stable—as is climate in keeping with long-term natural variation (i.e., no anthropogenic contribution).

Each of these is demonstrably and overwhelmingly false, yet many would have to be simultaneously true to be convincing. Modernity, therefore, doesn’t have a leg to stand on in arguing for prospects of its long-term continuance. It’s empty, sputtering hope. Not only do we obviously lack the track record to demonstrate longevity (on timescales relevant to evolution), but this set of conditions cannot be convincingly illustrated even in theory—while paying attention to the full context. No one really knows how any of this could work, long-term, in anything other than vague, hand-wavy form.

Some might say that I am equally hand-wavy—unable to offer conclusive proof of modernity’s terminal condition. Sure: no one can claim certainty about the future, but I ask: which seems like a safer bet to manifest into the indefinite future:

- A new mode unknown to exist elsewhere in the universe, causing lightning-fast ecological degradation on Earth (mass extinction), and by means that are not evaluated in terms of ecological sustainability; or

- A reversion to the way things have worked for 99.9998% of Earth’s history?

Justifications

As a physicist, I came to value end-run arguments that quickly differentiate the possible from the impossible. I’m referring to symmetries and conservation laws that one can employ to cut past messy details in order to make confident statements about broad-brush aspects of a problem. While such powerful tools do not exist for predicting the course of humanity, by stepping back sufficiently far, it is easy enough to mark modernity as woefully unsustainable.

So here’s the question: if modernity is bound to fail (likely via inelegant collapse), what degree of longevity would justify its existence? Under the presumption that the inherent unsustainability of modernity means it perishes and that all its “gains” are lost, what toll on other species justifies the experience? Bear in mind that the longer it runs, the worse it is for everyone—human and more-than-human alike. Here’s a suggestive menu to help:

- Any duration (even 50 years) is awesome: I mean, lunar landings! Worth the damage.

- A few centuries, even if Earth takes many thousands of year to recover.

- It would need to go at least 1,000 years to justify itself, given the permanent toll on biodiversity.

- Many thousands of years would justify it, even if mass extinction is guaranteed (likely including humans).

- A million years, even if it results in extinction of most complex life on Earth (including humans).

Some might reject the premise, and imagine open-ended technological flourishing. Imagination allows many unconstrained flights, divorced from reality. My point is that we need to ground ourselves and not get carried away in unsupportable fantasy just because we like the sound of it.

Note that I doubt most of the options above are even viable, and it appears to be plausible that the duration thus far is enough to trigger a mass extinction. To my mind, if failure is practically guaranteed, and the cost is greater the longer the run, I have difficulty justifying any duration. I see it as a mistake: a misguided detour that separated us (most cultures today) from the community of life, to everyone’s detriment. Indigenous traditions that never embraced modernity—often on principle—have my enduring respect. They were right all along. Shunning property rights, money, human supremacy, and pronounced inequality seems like a wiser way to live: one that does not obviously run afoul of how the rest of the living world works.

I try to understand the disconnect between my view and mainstream views. If someone’s gut reaction is to dismiss talk of modernity’s demise as dismal doomerism, I wonder what bolsters their confidence in the opposite conclusion. What evidence points to a sustainable new normal? What mix of assumption, wishfulness, or analysis (in full ecological, temporal context) guides their reaction? How wide are their boundaries of analysis? How circumspect are they about things like ecology that we don’t fully understand? How counterfactual must they be to keep the faith? Is their reaction based on a simple dislike of the prospect of modernity’s end (note that I didn’t end up where I am by preference), and is that even relevant to how things will play out? Granted, it took me years to process and absorb my evolving view, so I can’t expect a quick turnaround in others. Once initiated, however, it appears to be a one-way road.