A recent journal article by Matthias Schmelzer and Tonny Nowshin outlines the risks of degrowth turning into an “inward-looking, provincial, localized, and eventually exclusive project within Western Europe and the Global North – one that focuses on securing decent living within Northern regions that are involved in ‘degrowth’.” To counter this risk, they propose that degrowth needs to prioritize the global justice perspective and solidarize itself with movements from the Global South, fighting together against historical and present-day (neo-)colonial relationships.

In degrowth, we often speak about how the relationship between the Global South and the Global North could look differently, for example “if the Global North reduces energy and materials, then the Global South would suffer less from extractivism” or “if the Global South formed a stronger alliance between states, then they could reduce reliance on Global North trading partners.” But we overlook the edges of those two terms – Global South and Global North – when we talk about justice possibilities for the futures ahead of us. What happens at these edges? And how can we understand these edges or points of encounter in the degrowth discourse?

A blogpost by Frank Jacobs calls ‘The West’ “the biggest gated community in the world”, highlighting how fences and walls are all connected worldwide to separate the rich countries from the poorer ones. In 2021, the population of this group of rich countries (Canada, US, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Israel, New Zealand, and Europe = EU + UK, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein) represented only 14% of the global population, but 56% of the global GDP income. At the same time, most of the world population, 86%, made do with less than half of the global GDP income, 44% (author’s calculation based on UN data).

Another map by Philippe Rekacewicz in Le Monde diplomatique places “Europe at the center of a walled world” emphasizing the deadliness of the European border regime, and the Mediterranean Sea in particular. Since 2014, 28,547 people have gone missing in the Mediterranean Sea – 2,797 in 2023 alone. However, these are only the official numbers and don’t consider the people who have gone missing on their way to the Mediterranean Sea while, for example, crossing the Sahara Desert, or the people who have gone missing after they arrived in Europe.

One way to make sense of the deadliness of border regimes is to place them within the current dominant socio-economic system of capitalism. Political scientist Fabian Georgi has coined the term “Fortress Capitalism” to connect the deadliness of the Fortress metaphor that we mostly know from discourses of ‘Fortress Europe’ with the dominant political-economic system of capitalism, and the structural violence against migrants and refugees.

Here, I address three of his central points and connect them to current events, as well as relevant degrowth literature, to gain a deeper understanding of the concept of fortress capitalism.

1. Fortress Capitalism describes the systemic repressive control of mobility through border regimes.

20 years ago, there were no fences and walls at the borders of the European Union. Since then, reinforcement of the outer border has drastically increased, with nowadays 13% of all borders being reinforced through walls and fences. This trend has particularly increased since 2014 (315 km reinforced borders) to 2,048 km reinforced borders in 2022.

At the same time, borders are also reinforced through other measures, such as externalization of border controls, deals with so-called third countries, tightening of civilian rescue at sea including its illegalization by arresting civil rescue ships, and simplified deportations. The most recent of such measures is Italy’s proposal on creating asylum seeker camps in Albania (currently on hold through an Albanian court ruling), or the Rwanda Treaty signed by Great Britain as “emergency legislation” to circumvent the UK Supreme Court ruling that the asylum deal with Rwanda is unlawful.

In the spring of 2023, the European Commission declared that if will provide further resources to fund increasing surveillance infrastructure, thus strengthening reinforcement of the European border regime yet again.

2. Border and migration regimes are part of the mode of regulation of global capitalism.

Contemporary border regimes can only be adequately understood if they are conceptually located as a part of the larger framework of global capitalism and its contradictions. One of the biggest contradictions we currently face is the “multi-dimensional crisis of ecological breakdown” driven by capitalism and its ever-increasing pursuit of growth.

While the consequences of this continuous breakdown are still mostly manageable in the capitalist centers of the Global North, many places in the Global South suffer under the increasing destruction of livelihoods while barely having contributed to the crises historically.

Against this background, capitalist centers put reinforced borders in place to secure their existence and reproduction. Those borders enable them to pacify, shift, and temporarily dissolve contradictions at ‘the outside’, so far keeping the consequences of the ecological and climate crisis mostly external to their territories.

3. Border regimes defend and protect the “imperial mode of living” of people living in the capitalist centers.

Under fortress capitalism controlling mobility through borders is elemental to the reproduction of capitalism, as they shield “the accumulation process and the imperial mode of living enjoyed by privileged groups, from disturbances by uncontrolled working class mobility.”

By definition the imperial mode of living cannot be extended in an infinite manner, as it relies on unlimited access to land, labor, resources, and sinks outside the capitalist centers. At the same time, it has become increasingly attractive to the new global middle class that is evolving worldwide.

In this sense there is increasing competition about who can have access to the imperial mode of living, whose privileges can only be preserved for a small minority through an ever-increasing level of violence. According to political scientist Jens Wissel “the central function of the post-fordist border is to defend the imperial mode of life”.

So, what does this mean for degrowth and its global justice perspective?

The concept of fortress capitalism shows us how interconnected global justice questions are with border regimes and the reproduction of the capitalist system. According to Fabian Georgi, it is not possible to fight for global and social justice without acknowledging these deep connections. This is also true for degrowth’s fight for global justice, that cannot ignore how the capitalist centers protect themselves and their imperial mode of living through violent border regimes against mobility from the Global South and the consequences of capitalist contradictions in various geographies.

Here, it is important that degrowth stays open and places global justice at its center, so as not to turn into the inward-looking, provincial, and localized concept that Matthias Schmelzer and Tonny Nowshin warn against. Or possibly worse, by erecting, what I call “Fortress Degrowth” against the rest of the world, as right-wing interpretations of degrowth have called for indirectly through population control in the Global South, ethnic racism based on the idea that there are naturally unequal types of humans that should not mix, and the claim that people should stay where they ‘belong’.

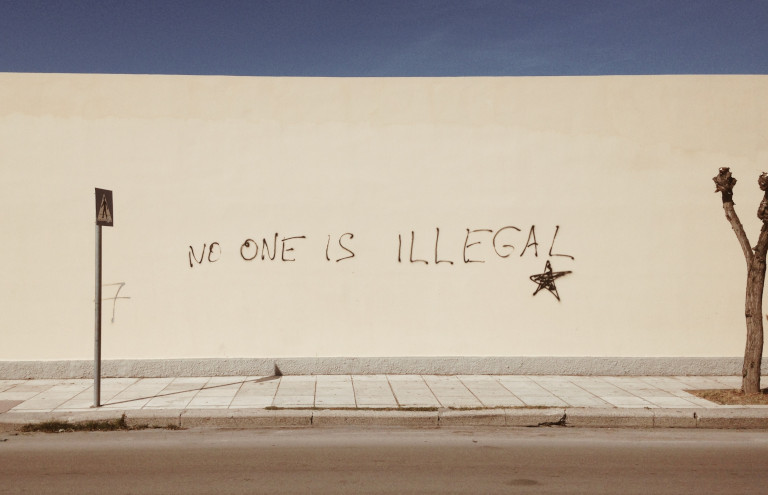

These claims cannot be supported by an anti-capitalist, feminist and decolonial degrowth understanding that places the global justice perspective at the center of the debate. Here, degrowth stands strongly at the side of the No border network and speaks up for global freedom of movement, meaning both the right to move and the right to stay. However, that alone is not enough. The fight against borders and for freedom of movement needs to be part of a deeper social-ecological transformation that places global justice at its core.

If degrowth only stands with the freedom of movement without considering a deeper social-ecological transformation, this could steer and increase existing fears around the competition of public goods (such as housing, education, health care, etc.) that currently lead to anti-migration sentiments and the call for more repressive border regimes in the first place.

Degrowth needs to find the balance: when we think of freedom of movement, we also need to think of welfare policies, the right to housing, public safety nets, etc. And, when we think about socially just and ecologically sustainable public services, we also need to do so with a global justice perspective in mind that includes both people who move and people who want to stay.