The Global Energy Transition:

This is the seventh in a series addressing the global energy transition as an opportunity to interrupt continuing injustice, to examine and revise a global ethic of development in favor of a living economy of human and earth-centric values. Ed. note: You can find all of the previous posts in this series on Resilience.org here, here, here, here, here, and here.

The International Renewable Energy Association (IRENA) has determined that the greatest reserves of the minerals critical to the transition to a renewable energy economy lie within indigenous territories. The acceleration of the global energy transition re-centers the issue of colonialism, ‘aggressive development,’ the conflict between capital and earth, indigenous territorial rights, and demands a review of the legal underpinnings of this effort along with its social and environmental impacts.

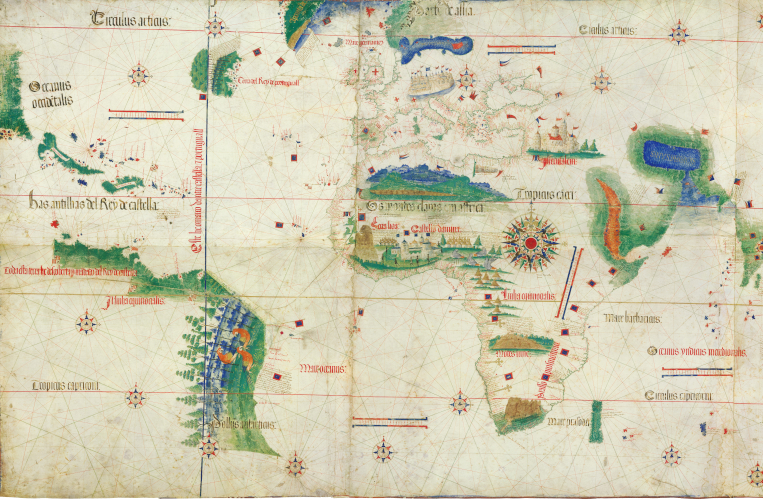

The Right of Discovery, contained in a Papal Bull in 1493, issued on behalf of Spain, declared the invasion, domination, conversion and oppression of indigenous populations (disavowed by the Vatican in 2023), within territories colonized by Europe to be entirely legal. This was followed some forty years later by an influential theological interpretation that regarded native populations as owners of their lands, thus generating the considerable history of negotiation and treaties signed by tribes and colonizers, including the American government. But that interpretation also declared that conquering Christian nations could assume the right to convert native populations by baptism, forcibly if necessary.

No acknowledgment of indigenous ownership, and regardless of how many treaties might have been signed, arrested the wholesale invasion, killing and appropriation of indigenous lands that followed in the ensuing centuries. The Doctrine of Discovery may be regarded as the underpinning of religious white supremacist claims on the New World. Continued justifications for those incursions in diverse parts of the world are historical revisionism, claiming that natives had no real land rights to begin with, or that violation of those rights can continue with impunity, have led to violence and murder

The Regalian Doctrine, the Spanish version of the Doctrine of Discovery, is another declaration pulled entirely from thin air by the colonial powers of Europe that all lands required title to prove ownership. And by whose authority was title conferred? The King, of course. Thus, the principle of private property was introduced to colonies across the world. Anyone who contested the authority of the King, or the primacy of title, was deemed savage, backward, illegitimate. State, religion, and plain greed presumed cultural supremacy. All conspired to demolish centuries-old societies for whom the idea of individual land ownership was inconceivable.

Even the Supreme Court of the United States split hairs in deciding in 1823 that even though native tribes were the ‘rightful occupants of their land,’ the discovering nation had a ‘preemptive right’ to all lands within US territory previously unknown to Europeans. Native American nations weren’t a party to that decision and weren’t consulted about it. By legal sleight of hand, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that decision nine years later. Since then, the history of American Supreme Court decisions on the issue of native land rights and the doctrine of discovery is a litany of erosion. There is no evidence of serious inquiry to verify history, to account for the many horrific injustices visited upon native populations, known and unknown, or to refine a practical or binding modern understanding of indigenous rights.

Evidence of this state of affairs is confirmed by reviewing City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation, 544 U.S. 197 (2005). After purchasing on the open market properties that were originally included within the boundaries of the Oneida Nation reservation, the City of Sherrill, NY attempted to collect property taxes from the tribe. The properties in question had originally been taken by the State of New York in violation of existing treaties. Since the properties remained within the reservation, the Oneida nation disputed the authority of the City to impose such taxes. The Court ruled against the Oneida Nation, fabricating a ruling that upheld 200 years of illegal takings from native people.

This unprecedented, rogue decision, which has been called the Plessey v. Ferguson of Indian law–rather than correcting the history of white supremacy and colonial onslaught against Indigenous peoples, re-affirmed the colonial rule inherent in the doctrine of Christian discovery and domination. Source

The author of the majority decision? Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the champion of women’s rights which had been colonized, usurped, denied, and exploited for centuries. Her decision referred specifically to the Doctrine of Discovery continuing to hold sway two hundred years later. The result was like telling a rape victim that since the injury happened so long ago, or due to the delay in reporting the crime, even if the culprit is known, that nothing could be done. For native nations, the land is their body. But Justice Ginsburg did not see the parallel. According to her, “Tribal sovereignty, [bodily sovereignty?] was a quaint and antiquated notion not worthy of consideration.” The passage of time had made history irrelevant.

The Oneida claim was followed in relatively short order by three more decisions (Cayuga, Oneida, and Onondaga) which further undermined, by either dismissal or by convoluted logic inventing legal exceptions, virtually any legal basis for granting native land claims. The claims were either too far removed from the original injustice, too disruptive or too much of a burden on those who had no role in the original injustice. If there is insufficient legal basis for a tribe to claim its own land, on what basis could they hope to claim a determinative role in the disposition of resources on that land?

One might well ask under these circumstances, if the right of self-determination continues to be usurped from indigenous peoples, of what use is the principle of Free, Prior, Informed Consent (FPIC) , enshrined in the language of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Populations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the ILO’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention 169? Since its adoption, there are large variations in the interpretation and implementation of FPIC among nations, companies, financial institutions, and indigenous peoples. In fact, there is no universally accepted definition. The issue, after all, is an attempt to reconcile two rather dramatically different world views and systems of knowledge. In that ongoing and intensifying encounter, there can be radical differences in the way disputes are resolved. While recognition of indigenous rights to customs, culture, and spiritual practices are more universally accepted, veto rights to the development of resources lying within that land have been the universal sticking point.

Failure of the FPIC process can rest on misunderstandings, deliberate disregard, or honest disagreements about what constitutes either consultation or consent or both. Tribes regard the creation of the UNDRIP and FPIC as measures restoring a right of self-determination which had been taken from them. A logical interpretation of self-determination would include the restoration of consent. But generally, the equalization of power imbalances between national governments, private companies and tribes implied by FPIC has not been born out in practice. Each new encounter demands a fresh interpretation of law, best practices, and risk mitigation. What is at stake for tribes is their long-term health and vitality. What is at stake for companies is their social license to operate. What is at stake for governments and the general population is the direction of development and the rights of all people to live in a healthy environment.

This is not to suggest that all disputes have weighed against indigenous interests. But the victories are few and far between:

- In 2007, two hundred tribes in British Columbia crafted their own FPIC protocols focusing specifically on mining. In 2023, a coalition of tribes sued the Canadian government for $95 billion in reparations for past wrongs.

- In 2016, the high court of Costa Rica blocked the national electric utility from progressing on the development of a 650MW hydroelectric plant because the tribe whose land was to be flooded was not properly consulted. The project has been stalled since 2011.

- In 2022, Ecuador’s Constitutional Court ruled the environmental permit granted in 2011 for the major San Carlos Panantza copper project required a consultation with the Shuar Arutam community, which was not carried out. Indigenous community leaders gathered in Puyo argued that the court ruling annulled the environmental license held by ExplorCobres SA, a unit of China’s CRCC-Tongguan Investment.

- Sierra Leone is permitting communities to veto mining, farming and industrial projects.

The case of the United States is not even the most severe model of how nations have disregarded native rights for the sake of development. Throughout the Asia-Pacific region, Central America, the Caribbean, South America, and Africa the proceedings are slow, fraught with illegalities, negligence, destruction of records, overnight reversals of rulings, harassment and arrests of protesters, reversals of mining bans, even murder. Full veto power is rarely if ever extended to a native community. Instead, the wheels of extraction may move slowly, but they eventually move over everything in their way.

Even though the International Council on Mining and Materials (ICMM), an industry association of some 30 companies (many of whom are in the most destructive precious metals sector), has pledged ‘constructive relationships between mining and metals companies, and Indigenous Peoples based on mutual respect, meaningful engagement, trust, and mutual benefit.’ Even though the muddy proposition of FPIC is becoming an industry ‘best practice,’ a risk-reduction practice, the inescapable conclusion is that the intention of the process is tied to a specific outcome of consent. FPIC is not a neutral or a political exercise that automatically improves democratic governance. That’s the business model of the industry. And there is a long-established basis for confidence, regardless of how meticulous and accommodating their implementation of FPIC may be, that they are prepared to outlast, out maneuver, out lobby and outspend any opposition until their principal objective is attained.

The entire imperative of modernity to sustain itself, to continue the illusion of mastery over nature, to ensure industrial ‘sustainability’ and cultural permanency, and the continued ascent of humans to the pinnacle of promised divinity is a recapitulation of the colonial enterprise, now accelerating toward an apotheosis within the foreseeable future.

Extracting mineral resources with little thought of their finite nature, motivated entirely by rationality, removing intuition or systems analysis from the process, mindlessly continuing based solely on the imperative of abundant cheap energy provided by fossil fuels and by the pursuit of market advantage, repelling any inclination to reconsider what the concept of private ‘ownership’ of land has brought us, driven by debt and profit, the architecture of the plantation is preserved. Indigenous populations are reminded once again that they are field hands and shall never be permitted to control their own destiny when it comes to the narrative of Progress. The extension of mining into indigenous lands is inexorably expanding the creation of environmental ‘sacrifice zones’ in the ancestral territories of native populations.

No single project can be blamed for the inertia of the Machine. No reversal of any single project can be counted on to stall the Machine. But the cumulative effect is rolling us into an increasingly uncertain future. For indigenous peoples, it isn’t so much control of their destiny that is even most important in this scenario. It’s the principle of private ownership of land at the expense of collective stewardship, shared responsibility for each other, the land and water, taking guidance from (increasingly disrupted) seasons, the wildlife, the ebb and flow of life, and above all, giving thanks for all of it. Fighting for the principle of self-determination in a culture that divides, manipulates, surveils, commodifies, and extracts might ultimately be a thwarted effort. The real contribution of native tribes at this point might be to be more aggressive in showing us exactly what we are losing. Will that make any difference?

Citations:

Chinese Mining and Indigenous Resistance in Ecuador

Conceptualizing Free, Prior and Informed Consent: Interpreting Interpretations of FPIC, Columbia Academic Commons

Exploring China’s Footprint in the Andes Mountains: Copper Mining in Ecuador

Indigenous Peoples and Mining: Position Statement

Inter Caetera, The Papal Bull of May 4, 1493

Reappraising the Doctrine of Discovery

Vatican Formally Repudiates Doctrine of Discovery