Our Autumn 2023 full colour edition is an ensemble exploration of the eight ceremonial fires of the year, celebrated in practices, stories, poetry and artwork.

Our Autumn 2023 full colour edition is an ensemble exploration of the eight ceremonial fires of the year, celebrated in practices, stories, poetry and artwork.

We are waiting, holding our breath in the dark, perched in trees, standing among reeds, holding vigil by an unlit fire. They’re coming! As we peer through masks of crow and badger, heron and fox, we can see the people cross the bridge from the town carrying small red lights in their hands. Soon, following the bearers in black coats and bowler hats, they will stumble across us, as a silent path wends around this island in the river Thames. Then the fire will be lit and there will be stories and singing and toasting into the night. The river will carry on flowing down to the sea, as it has always done, as long as our ancestors can remember.

This is spring equinox 2017 in the town of Reading, England, one of many Dark Mountain gatherings we have held around fires during the last decade. Small encounters in the dark that brought us together in ways we could never have imagined in the modern brightly lit rooms of towns and cities before we knew of the collapse and calamity of the world. The fires and gatherings were always central to the project; indeed our books, the art and writing and teachings, are all created around this hearth, as the animals and ancestors stand behind us, as the night breathes us in.

In 2022, we took an ember from a spring gathering that had been cancelled by lockdown, and blew on it. Its name, ‘How We Walk Through the Fire’, became a series of workshops revolving around the eight fires of the ancestral solar year. These were hosted online but involved encounters in real life. The idea was simple: we would build a cultural practice together that could weather the storm of converging crises using the ‘stone clock’ of the equinoxes and solstices and the four stations of the growing year, known by their Celtic names: Imbolc, Beltane (or May Day), Lughnasadh, and Samhain. Each fire would be a marking, a celebration of our local wild and feral places, and a way of reconnecting ourselves – with our bodies and imaginations and one another.

After the first introductory meeting, we would collect sticks on a walk into our territory and build a fire to mark the shift of season. For the second meeting we would bring back a fire stick and relate what happened when we held those fires: how we made them or failed to make them, what occurred in the wind and rain and snow; we shared stories about the birds we encountered, the waters we honoured, the trees we sat beneath, and the mythic layers of the earth beneath our feet. And then, as if gathering round a real fire, we would present a piece of work – story, poem, dance, song, making, art – created from our experiences.

The Stone Clock by Caroline Ross

This book has been inspired by those workshops, a collective journal of encounters and witnessing in many places. From the beginning, Dark Mountain set out to gather stories rooted in place and time that are not focused on the drive of progress, that do not centre the human as the pinnacle and purpose of this planet. But the question remains: how do we do this in our practical lives beyond the page? When we are fatally entangled in a civilisation that restricts our being anything other than a consumer of resources and entertainment?

The Eight Fires practice took another path in the woods, following the dramaturgical strand of the project. We met as an assemblage of human beings, raised in the ruins of late capitalism, who exchanged their engagements with places, framed by an ancient calendar that asks different things of us as people. To listen to the polyphony of each other’s voices as a way of breaking out of the monologue of modernity. If the core cause of the current environmental crises is an existential separation from nature, each journey was an attempt to rejoin the living world outside our doors, to close the gap beyond just thinking about it. The immersive work we undertook was simple, the testimonies unpolished works-in-progress – words woven from grass and rain, staffs made from driftwood and windblown feathers –and yet these portals salvaged from the fabric of our territories keyed us into the geographies of everywhere. The woods we visited became the planet’s forests; each hill, its many mountains; the neighbourhood parks, the green breathing spaces of every city.

Walking barefoot on reindeer moss we remembered the Arctic, sharing weather reports connected a zephyr on a street corner in Paris with the chinook rattling wind chimes in Alaska with the lack of wind in a stifling afternoon in Kerala. Our small ceremonies held in rooftop and riverbank gatherings, in winter gales and heatwaves, were all treasured in the meetings that worked as a container. Our bodies were our memory lockers, the fires a way of remembering how to live as real human beings, of doing the work of transformation that Gary Synder once called ‘hard yoga for planet Earth’, following a road map that is ancient and global and has been practised for millennia.

It felt, despite the current state of collapse, that this attention helped us engage in what the Aboriginal academic Tyson Yunkaporta describes as an ‘increase ceremony’: to thicken the web of correspondences between place and people, ancestors, and the more-than-human world. We were creating an invisible network that you could feel in the online sessions even though we were not meeting in the physical world – a sharing of ceremony, even though we were continents apart.

The form of these fire-based meetings took the shapes of a ceilidh and a kiva. Above ground, they mirrored the convivial sharing of songs, poetry and stories in the Scottish and Irish tradition. But below these festive convergences a deeper meeting was held, in what we called the ‘kiva’ attention – named after the underground ceremonial chambers of the Southwestern Pueblo people, linked with the cycle of the year.

In parallel with storyteller Clarissa Pinkola Estés’ ‘rio abajo rio’, this was ‘the fire beneath the fire’, the bones of the mythos that underpins the narrative body of any transformative story. So although our meetings were creative and celebratory, there was an acknowledgment that their meaning was being played out in another dimension: we were making moves in our collective and inner lives, realigning ourselves with the movements of the sun and the Earth – small radical acts in a civilisation that does everything in its power to keep people deracinated and hostage to the drive of the 24/7 clock.

The firekeeping practice became a way to resist those forces, to access our deep-time knowledge and put us in sync with the Earth’s rhythms and metabolism, kin with the thousands of people who are holding fires and doing this regenerative culture making at the same time. It brought depth, resonance, belonging, a capacity to face the storm that would not have happened on our own.

Firestick by Caroline Ross

This is a book of practices, testimony, tools, ceremony, stories, art and poetry, inspired by the 82 people who went into their local territories to make an embodied connection with the more-than-human worlds, and brought back its treasures. It has been created both by the ‘firekeepers’ who took part in the workshops, and by artists and writers who have responded to the ideas behind our collaborative practice. It is shaped around the eight fires, following the themes we focused on, with the opening of the practice at winter solstice, and a holding fast at the zenith of summer solstice, looking forward and back at the cycles of the year.

It is a book made of wild winds, seaweed shelters, glass mushrooms, talking fire sticks, singing stones, moments of joy, grief and intense physical immersion in a sentient planet. It is rough and nonlinear, and can be read in sequence or by leaping into any of its eight seasonal sections. Most of all it tells a story about reforging an imaginative relationship with the Earth at a time of reckoning; about connecting deeply to the places we live in in a culture fraught by forgetting and isolation, and learning to find words for our encounters and acts of relinquishment and restoration, embedding them in creative work and sharing it with others. It’s about dancing with bears, listening to mountains, sleeping with trees; a reminder of how we can speak together around a fire when the animals and ancestors are standing behind us. It’s a map, a manual, a sketch book, a raggle-taggle lexicon, a collective love song to life in a collapsing world.

We hope that you enjoy it and find it useful in the years to come. And maybe one day, we will meet around one of these eight fires, as we did at that spring equinox long ago, with a river flowing beside us, a wind in the trees, people laughing and singing together in the dark, as we always have, in deep time.

Gathering Sticks for the Eight Fires

This practice can be used as a basis for any of the fires, adjusting the questions to the seasonal cycle.

Find a time to walk into your territory, bearing the time of the fire in mind, taking note of the shift of season, the change of mood and temperature, the scent of the wind, the colour of leaves, the sounds of the insects, the birds gathering in the trees.

Make time to lie on the earth and look up at the sky, and to notice the clouds and the change of light. Tap into how this makes you feel. On your way home, gather some sticks for your fire. Make sure the twigs or small branches are dry.

As dusk comes you can make a fire using your bundle of twigs as kindling, either in the territory itself or at home. This can be as small or large as you like and will depend on where you live, but even if you don’t have a place available, a small twig fire in a can or metal dish on a balcony or rooftop will do just fine!

Once lit, whether a solo or convivial fire, sit with the fire and tend to it for at least 15 minutes to tune into this moment of the turning solar year. Engaging in the eight ‘doors’ of this year is an imaginative practice to help reflect on our life in sync with the seasons and the times we live in, to rekindle the ancestral knowledge we hold and our relationship with the sun in the growing, birth, and death cycle of the year.

Each fire marks the energetic shifts from one season to the next: from the dark of winter to the light of spring, from the autumn harvest toward the underground roots of winter. Attending the fire engages the attention in the cyclic process that both takes part in life and feeds back to life on all levels.

As you watch the fire, you might like to consider and/or speak out loud what you are letting go of and what you are stepping into. You might ask:

What can I relinquish that will feed the fire, the spirit of the world?

What is being required from me in these times of downshift?

Who are the ancestors who can help us remember who we really are?

What does the fire tell us?

Make sure the fire is well out before you go indoors.

At daybreak the next day, go out and greet the sun as it rises.

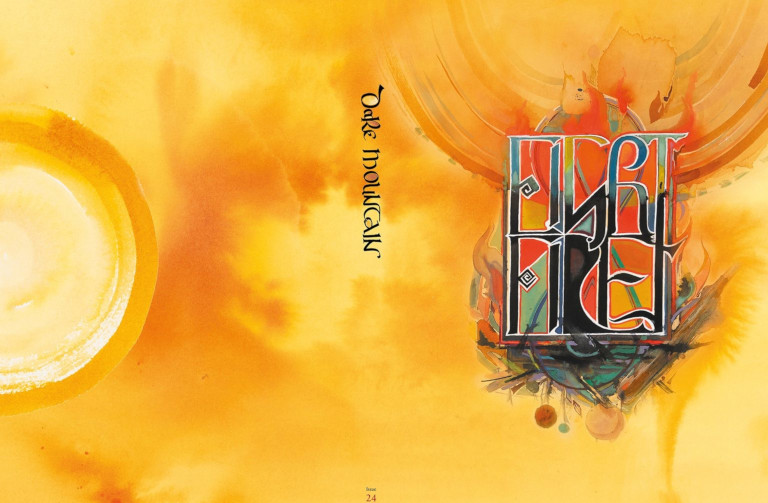

Images:

Candace Jensen

Eight Fires (series of 11 works)

Watercolour, hand-made floral inks and galls, mushroom spores, gouache, ink, graphite and freshly gathered charcoal on torn arches and Fabriano papers.

The design of the cover and section titles are directly inspired by letterforms and inks found in the Book of Kells and an edition of the Carmina Gadelica. Their making is rooted in the tradition of illuminated manuscripts, in which gilded, intricately-painted letters made by hand, honour the sum of their implied sounds and meanings as sacred. These are an intentionally wild calligraphy made with carefully rendered organic shapes of charred wood, stone circles, ash heaps scribed by the wind, and embedded seeds or hairs in the paper. There are languages spoken on the page between the inks, the pigments, and the paper fibres themselves.

Candace Jensen is a visual artist, writer, calligrapher and organiser. Her ‘Gaia Illuminations’ are visual essays which expand calligraphy’s traditional cultural reliquary beyond the limits of anthropocentrism. Jensen is co-founder and Programming Director of In Situ Polyculture Commons, an arts residency and regenerative culture catalyst, and lives on the unceded lands of the Elnu Abenaki in southern Vermont.

Caroline Ross (pictographs, set of 6) is a writer and natural and ancient materials artist living in Dorset. She is the author of Found and Ground – a Practical Guide to Making Foraged Paints (Search Press) and a long-time regular contributor to Dark Mountain. Instagram @foundandground; Substack @uncivilsavant