CHESTER, PA — When Zulene Mayfield testifies next week against plans to build a $6.8 billion liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal in her Pennsylvania hometown, she will be facing off against some of the most powerful fossil fuel interests in the United States.

As co-founder of the community group Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living, Mayfield has spent years fighting to protect her majority Black and low-income city from the pollution spewed by the nearby Covanta waste-to-energy facility — the country’s largest waste incinerator.

Now she finds herself pitted against a new confluence of forces — a lobbying effort by a fossil fuel complex stretching from her state’s Marcellus Shale gas fields to the boardrooms of European energy companies.

“Why do we always have to justify our position to live in a clean, healthy, and safe environment?” asks Mayfield, who told DeSmog that Chester residents have nothing to gain, and much to lose, from the proposed LNG terminal.

The hearing, scheduled for August 22 at Widener University, will be the final public meeting of the Philadelphia LNG Task Force, and the first time Mayfield, among the most vocal critics of the plan, has been allowed to voice her concerns in person.

The task force was established by the state’s House of Representatives last November to explore prospects for shipping regionally produced shale gas to Europe in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Texas and Louisiana produced record amounts of shale gas last year, which U.S. LNG companies shipped to Europe at soaring premiums. In Pennsylvania, however, output from the state’s fracking fields declined for the first time in more than a decade — a trend the U.S. Department of Energy blamed on falling productivity and export bottlenecks.

A company named Penn America Energy has proposed Chester as the site of the largest LNG export terminal on the U.S. eastern seaboard, which could reverse the decline. The company says this terminal will become the leading purchaser of gas fracked from the Marcellus Shale, the gas-rich underground deposit stretching across Pennsylvania, New York, West Virginia, and Ohio.

The proposed terminal is one of approximately 20 planned new LNG export facilities nationwide. Many have already received approvals from federal regulators, despite often fierce opposition from local communities, which have expressed fears that the terminals will cause toxic air pollution and ruin local landscapes, as well as run the risk of deadly explosions. Some also worry about the destructive climate impacts that would come with the associated expansion of the fracking industry.

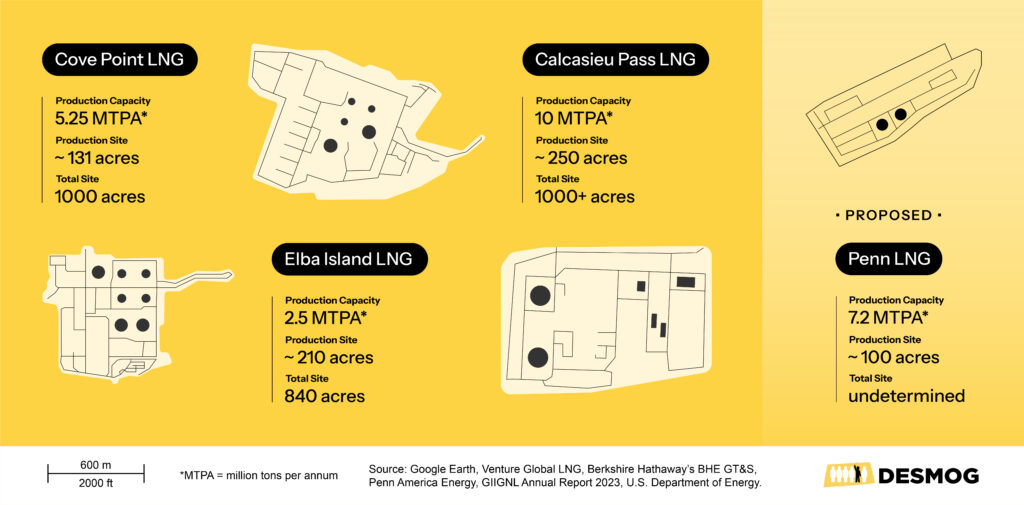

Site size and production capacity for LNG export terminals.

Environmental groups on both sides of the Atlantic warn that the U.S. LNG boom threatens to release vast amounts of methane, a powerful climate pollutant that is the main component of natural gas. The U.S. gas export industry emits the most methane relative to other major suppliers, according to a UK government analysis published in 2019, with leaks occurring in voluminous quantities during production, transport, and storage.

Likewise, European campaigners fear that the continent’s scramble to replace Russian pipeline gas with imported LNG will undermine a European Union target to slash carbon emissions 55 percent from 1990 levels by 2030, and lock countries such as Germany and Poland into dependence on imported fossil fuels for decades.

“As a result of the war against Ukraine, we [face] the great danger of slipping from one dependency to another, a new fossil lock-in, instead of reaching the goal of 100 percent renewable energy,”

said Kathrin Henneberger, a Green Party parliamentarian in Germany, which has begun importing U.S. LNG to make up the shortfall from Russia.

Penn America Energy did not respond to repeated emails with questions submitted by DeSmog.

“Kill Zone”

The first time Mayfield and many other Chester residents heard of Penn America Energy’s plans was in June 2022, when the regional public media organization WHYY revealed that the company had been shopping around plans to build an LNG terminal on Chester’s Delaware River waterfront since as early as 2016.

For Mayfield, the choice of Chester — where the poverty rate is more than twice the national average, and the municipal government recently declared bankruptcy — follows a familiar pattern.

“We have a number of environmental issues in our city, but above all is the environmental racism that has occurred to us as residents,” Mayfield said. “It appears that everybody wants us to take their trash, their sewage and now the gas for everybody else’s comfort.”

If built on the Chester waterfront, the proposed 100-acre Penn America Energy plant would become the most compact LNG terminal in the U.S., and the first in such a densely populated area, according to a DeSmog analysis of satellite data and company records.

For comparison, an LNG terminal in Cove Point, Maryland — which exports about 40 percent less LNG than planned capacity of the Penn America Energy facility — has approximately 125 acres of built infrastructure, on 1,000 acres of land.

Homes in Chester, Pennsylvania, directly next to the proposed site for the LNG terminal. Credit: Edward Donnelly.

Architectural renderings of plans for the company’s plans in Chester show an approximately 25-acre parkland buffer to be added in front of the terminal. That area is currently occupied by dozens of homes, three churches, a daycare center, and several local businesses. But even in places where LNG terminals are built further away from homes, residents often find the fenceline too close for comfort.

For years, engineers have warned of the risk that the volatile refrigerant gasses used to supercool natural gas into liquid form can ignite to cause what is known as a “boiling liquid expanding vapor cloud explosion” — or BLEVE, in industry jargon.

On June 8, 2022, just such an explosion at the Freeport LNG export plant in Texas released a 450-foot-high fireball, shuttering the plant for nine months. While that blast was contained, a vapor cloud explosion at an LNG terminal in Algeria in 2004 killed 27 people.

Penn America Energy says its proposed terminal would operate to the highest safety standards. But Mayfield said the project would create a “kill zone” in Chester, where 33,000 residents live in a five square mile area.

Safety concerns have delayed another LNG export project located about three miles from Chester, on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River. In April, federal regulators struck down a permit extension for the developer — New Fortress Energy — to supply LNG to the plant by railroad. While no specific reason was given for the decision, local campaigners had warned of potential risks posed by the hazardous freight.

The Delaware Riverkeeper Network — a regional environmental organization fighting both the New Jersey and Pennsylvania LNG terminal plans — says that fracking for shale gas causes “unparalleled” damage to air quality, water resources, and farmland.

Penn America Energy advertises the Marcellus Shale as the source of the “world’s cleanest natural gas.” The Yale School of Public Health, however, released a study last year that found that Pennsylvania children living near fracking wells have a two to three times elevated risk of a form of childhood leukemia.

Barred Entry

Despite widespread concerns about the project being built in Chester, Mayfield has had to fight to get her voice heard.

When Pennsylvania state Sen. Gene Yaw (R) convened a meeting to discuss the project at the Steamfitters Local 420 union hall in northeast Philadelphia last October, Mayfield was turned away.

So, instead, she organized a small protest in the parking lot alongside residents from Chester and greater Philadelphia.

Yaw, who represents rural counties in the Marcellus Shale region, described the project’s opponents in a subsequent op-ed as “a few costumed protestors who would clearly favor Russian domination over the global energy market.”

When state Rep. Martina White (R), the chair of the Pennsylvania LNG Task Force, began holding hearings in April, she soon faced accusations of packing meetings with local pro-LNG allies.

The task force’s members include the Pennsylvania director of the American Petroleum Institute, the most powerful fossil fuel lobby group in the U.S., as well as a member of the Steamfitters Local 420 union, which supports the project. The union has provided White with more than $87,000 in donations since 2017, according to campaign finance data from Transparency USA.

The task force heard some of its first testimony in support of the project from the Pilots’ Association for the Bay and River Delaware, which donated $5,000 to White last year, finance records show.

An LNG tanker puts out to sea in Świnoujście, Poland. Credit: Edward Donnelly.

“Cleaning Up”

One of the project’s most vocal supporters also has a seat on the task force: Toby Rice, chief executive of Pittsburgh-based fracking company EQT, the country’s largest natural gas producer. EQT has been at the forefront of the U.S. fracking industry’s attempts to capitalize on Europe’s search for alternatives to Russian gas, targeting buyers from Germany to eastern Europe. Supporters of EQT’s “Unleashing U.S. LNG” campaign can now buy trucker caps bearing the slogan “Marcellus over Moscow.”

At a June event with German gas lobby group Zukunft Gas in Berlin, Rice promoted U.S. LNG as cheap, reliable, and the best bet of any energy source to meet Germany’s 2045 target for carbon neutrality.

“Because of the environmental progress we’ve made on eliminating methane emissions and cleaning up our carbon footprints, we are positioned to deliver these cargoes to the doorstep of Europe in a net zero fashion,” said Rice.

Climate campaigners argue that claims of “net zero” LNG are misleading because — even in the unlikely event that the industry tackled all its methane leaks — the gas is typically burned in power stations that emit huge quantities of planet-warming carbon dioxide.

Despite these climate concerns, European governments have been quick to embrace U.S. LNG imports, which increased by about 140 percent last year as Russian pipeline supplies dwindled.

Supporters of the oil and gas industry’s expansion plans have been quick to enlist European public figures to champion their cause.

The Żerań Power Station in Warsaw, Poland, is being converted from coal to gas power. Credit: Edward Donnelly.

At the October 2022 meeting, convened by Sen. Yaw to discuss the Chester terminal, Michał Kurtyka, who served as Polish environment minister between 2019 and 2021, joined by video to speak in favor of the plan.

“The most obvious choice for Europe is for LNG based on transatlantic solidarity,” said Kurtyka, who was president of the annual United Nations climate talks held in the Polish city of Katowice in 2018. Kurtyka noted that Poland had “done its work” to shift away from Russian gas in recent years, opening its first LNG import terminal on the Baltic Sea coast in 2015.

Polish environmental groups attribute their government’s enthusiasm for U.S. LNG in large part to effective lobbying by Poland’s fossil fuel industry. Orlen, a Polish oil and gas conglomerate, owns one of the country’s largest media companies, and has close ties to the ruling Law and Justice Party, which has faced criticism from campaigners for failing to unleash the full potential of the country’s renewable industry.

In Poland, natural gas is widely seen as a cleaner alternative to coal, which still produces most of the country’s electricity and much of its home heating, but contributes to about 48,000 premature deaths from air pollution a year, according to the environmental collective Polish Smog Alert.

Polish campaigners say the country could meet its energy needs by embracing a faster roll out of energy efficiency and renewables, rather than tying itself into long-term dependence on U.S. natural gas.

Ongoing expansion of the LNG import terminal in Świnoujście, Poland. Credit: Edward Donnelly.

“Expanding renewables makes the coal-versus-gas debate obsolete,” said Diana Maciąga, a Krakow-based climate campaigner. “The focus should be on energy efficiency and ensuring the rapid deployment of wind and solar, which will permanently reduce costs from fossil fuels as the role of coal and gas becomes strictly limited to reserve capacities.”

For years, planning rules effectively restricted the development of onshore wind turbines to 0.3 percent of Poland’s land area. New rules have expanded that proportion to seven percent, but critics say that extension still excludes two-thirds of the country’s onshore wind potential.

Defying Warnings

Then there’s the question of whether projects like a Pennsylvania LNG terminal will be operational in time to answer the drive to get off Russian natural gas.

If it opens on schedule, a facility in Chester would come online in 2028, according to Penn America Energy’s timeline. Following the Ukraine invasion, the European Commission launched REPowerEU, a strategy to save energy and diversify supplies. Within eight months of the policies taking effect, the EU had replaced 80 percent of the gas previously supplied by pipeline from Russia.

Last winter, the EU managed to slash its gas use by 18 percent, defying warnings from the fossil fuel industry of winter blackouts. Poland has mirrored this trend, with natural gas consumption falling last year, in a climate of volatile prices — even as solar power enjoyed a record year, with new installed capacity growing 29 percent.

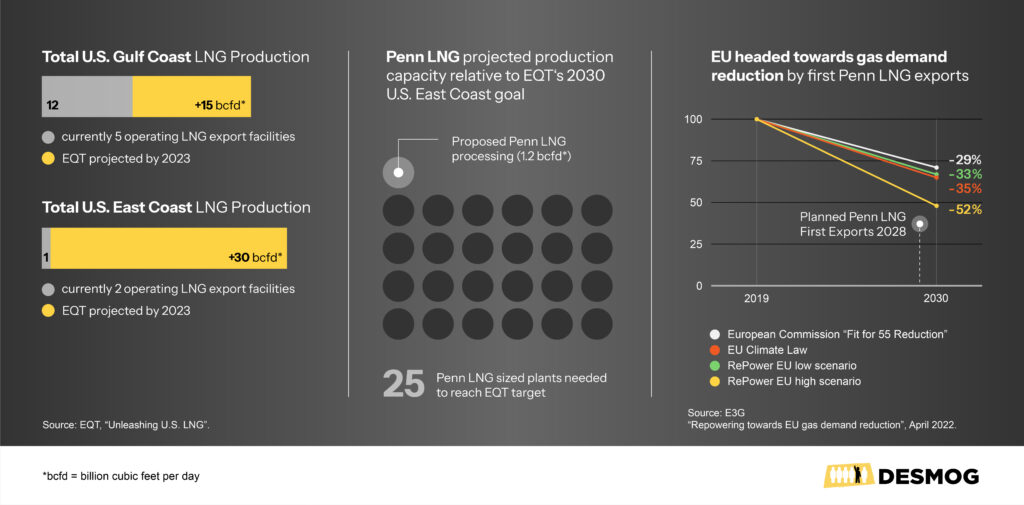

EQT projects an increase in U.S. LNG production, even as EU demand for the fuel declines.

E3G, a climate research group, estimated in October 2022 that the EU’s energy and climate targets could reduce natural gas consumption by 29-52 percent by 2030. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a think tank, expects European demand for LNG to peak this year before declining, while the Paris-based International Energy Agency sees most LNG growth occurring not in Europe, but Asia.

Such predictions have done little to deter EQT’s Toby Rice, whose company aims to more than triple U.S. LNG exports by 2030. He has promoted a Pennsylvania LNG terminal as an “amazing opportunity” for Chester residents, as well as a boon for European allies.

State Rep. Carol Kazeem (D), who represents Chester, told Rice at a meeting of the LNG task force in May that she wanted job prospects for the economically struggling city, but that LNG terminals would not be the type of project for her constituents to be “proud of.”

Zulene Mayfield has summed up her objections even more bluntly.

“We are not anti-capitalist,” says Mayfield. “We are pro-survivalist.”

CORRECTION (08/18/23): This article has been updated to correct a typo in a graphic. Under the European Commission’s “Fit for 55 Reduction” natural gas demand would decline 29 percent, not 22 percent as originally indicated.