Ed. note: This article was published on The Tyee on March 23, 2023.

A Stanford study has confirmed the results of a Tyee investigation that identified a bitumen wastewater disposal well most likely triggered recent record earthquakes in Peace River country that rattled homes and shook Albertans as far away as Edmonton.

“Earthquakes of similar magnitude to the Peace River event could be damaging, even deadly, if they happened in more populated areas,” said study lead author Ryan Schultz in a press release, who recently completed his PhD in geophysics at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. “It is important that we understand the mechanics involved and how to avoid inducing more of these events.”

“The Peace River earthquake caught our interest because it occurred in an unusual place,” said co-author William Ellsworth, a research professor of geophysics and co-director of the Stanford Center for Induced and Triggered Seismicity. “Multiple lines of compelling evidence point to this quake as being manmade.”

But the earthquakes didn’t make much of an impression on the Alberta Energy Regulator, which first said the earthquakes were natural.

And the AER has refused to confirm or deny whether it was investigating two major heavy oil operations in Peace River as the source of the earthquakes.

The tremors, including the largest quake ever recorded in Alberta, all occurred near Baytex Energy Corp. Peace River operations and CNRL’s Peace River heavy oil project about 40 kilometres from the town of Peace River. CNRL’s operation was formally known as the Shell Carmon Creek Project.

Heavy oil projects, which inject pressurized steam in the ground over long periods of time to allow the oil to flow, can activate faults and cause small seismic events and even deform the landscape.

In addition to heavy oil wells, Baytex also operates an enhanced oil recovery water flooding operation that has injected 694,000 cubic metres of water mixed with polymers to push out heavy oil in the very same region shaken by the earthquakes.

Water injection from EOR operations have caused large earthquakes in both Snipe, Alberta, and Fort St. John, B.C.

Both Baytex and CNRL also continuously inject large volumes of wastewater from their operations deep into the ground — a known cause of large seismic activity.

According to the Stanford study Alberta bitumen steam plants have injected 100 million cubic metres of wastewater underground, about 40,000 Olympic swimming pools worth, since the 1980s.

The high volume of wastewater injected into the ground increased pressure on the fault, weakened it, and made it prone to slip.

The AER said little hydraulic fracturing takes place in the region but that was never the issue. Scientific and government reports have confirmed that the injection of fluids including steam, water or gas into the Earth’s crust can create or reactivate fractures triggering earthquakes damaging to local infrastructure.

Since last November Natural Resources Canada has recorded 11 tremors greater than magnitude 4 (and one as high as 5.6) near the two heavy oil projects which operate on more than 2,600 square kilometres of land. The events rattled the residents of Peace River and thousands of Albertans felt the quakes.

Last week the Peace River region was hit by another swarm of three earthquakes ranging from magnitude 4.6 to 5. Many of the tremors were felt as far away as Edmonton.

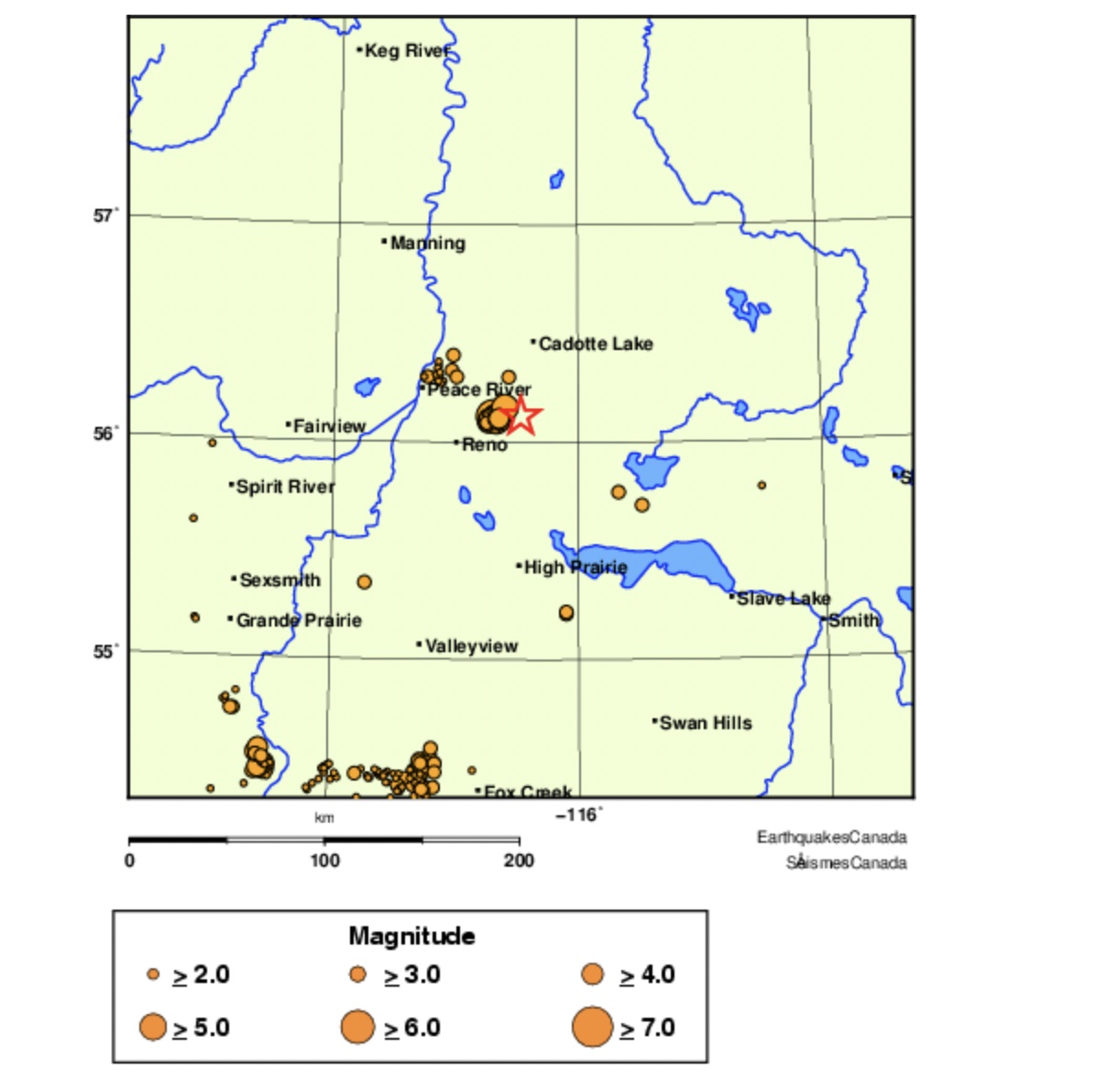

Alberta earthquakes with a magnitude of 2 or higher since the year 2000. Map via Earthquakes Canada.

Carmen Langer, a well-known local rancher who lives near the CNRL project, said the March quakes “shook the hell out of my home and cracked the cement floor. Pictures fell off the wall, too.”

Langer, who has publicly battled air pollution from crude bitumen storage facilities and a pulp mill in the region for decades, said he’s not surprised by the tremors.

“How can you continuously make big holes in the ground and not have something happen or connect to a fault,” asked Langer who says he has suffered heart attacks and strokes as a result of bitumen air pollution.

Langer also claims heavy oil operations have affected the contour of the ground and caused subsidence in some areas. “The ground is tilting in some places.”

Langer was not only the one who suspects bitumen steam or water flooding operations and their disposal wells may have triggered the quakes.

“Clearly there has been years of continuous injection of steam, millions of cubic metres, and that could have an impact on the geology,” said Paul Belanger, a science advisor to the Keepers of the Athabasca, an environmental group.

“The probability of these facilities causing the earthquakes is very high,” added Belanger, who has called for full public inquiry.

Gail Atkinson, a former professor at the University of Western Ontario and Canada Research Chair in Earthquake Hazards told The Tyee last year that industry fluid injection most likely triggered the November quakes because of their shallow depth.

But the Alberta Energy Regulator, which is funded by industry and has no public interest mandate, has stayed silent on the matter, and not answer repeated questions from The Tyee over the last three months.

When asked if CNRL’s operations were the source of either the November earthquake cluster or recent March events, the AER avoided the question.

In an email to The Tyee a representative said that “it is aware of multiple seismic events that occurred on March 16 around 8:46 a.m. in the Peace River Region… the Alberta Geological Survey, a branch of the AER, is investigating to determine cause, as well as any possible connection to seismic events which occurred in the area in November 2022.”

The AER also did not answer direct questions from The Tyee about the number of bitumen wells, deep disposal wells or hydraulic fracturing (fluid injection over short periods of time) in the region that might cause seismic activity.

“Within the parameters of the active investigation underway, the AER is committed to sharing updates and information as we are able to do so,” it said. But the secretive agency has released no information about what those parameters may be.

Yet the earthquakes all took place near Reno, Alberta, where Baytex’s Peace River operation is located. CNRL’s Peace River thermal in situ lies just northeast of quake zone.

Alberta’s steam plants in Peace River, Athabasca and Cold Lake produce 1.6 million barrels of oil a day by injecting pressurized steam into bitumen formations to melt the tar-like substance. A pump then extracts bitumen, water and gases from the same well. The province’s water intensive steam projects use 4.8 billion litres of water a day.

Industry has been injecting steam into the Peace River formations and extracting bitumen for decades. Experts say it is possible the steam may have found fractures and reached much greater depths, triggering an earthquake.

Earth fractures have happened before at heavy oil operations. At another steam injection project in Cold Lake, CNRL over pressurized the formation in 2013 with damaging results.

Pressure from the steam cracked rock between different formations, allowing melted bitumen to find natural fractures and flow to the surface at five different locations, including under a lake.

In some places, the bitumen erupted through fissures in the ground as long as 159 metres. The AER eventually found that CNRL failed to properly account for geological faults and fractures in the region it was steaming.

According to a 2023 Wood Mackenzie research report that has been removed from the internet, the Peace River/Carmon Creek plant capacity was 12,500 barrels of bitumen a day, but production in 2021 fell to 2,700 barrels per day.

As a result CNRL has tried to optimize the facility and pads by altering the volume of steam injection.

Because the AER would not disclose what oil and gas activities were located near the earthquake’s epicentre, The Tyee approached geological engineer Grant Ferguson at the University of Saskatchewan. Ferguson has written extensively about deep injection wells and studies the impact of oil and gas activity on deepwater systems.

In an email to The Tyee Ferguson confirmed that a large number of bitumen wells, including more than 80 steam injection wells, are located in the region shaken by the record tremors. Most of these steam injection wells are about 600 metres in depth. All belong either to Baytex or CNRL.

Shell, the previous owner of the Carmen project, operated an in-house microseismic program to detect seismic events that could signal failure of wellbore integrity or leaks of steam into other formations. Under Shell the project reported frequent microseismic activity.

Scientific studies have long noted that injecting steam at high pressures into the ground to melt bitumen can cause seismic activity as well as uplift and deform the ground to such a degree that the upwelling can be identified by satellite images.

Many seismic events occur between the periods of stress relaxation and stress activation after active steam injection in the formation. Pressure from high temperatures combined with ground deformation can also weaken wellbores causing failures which “may be detected as a larger magnitude seismic event close to the wellbore and above the injection zone,” noted one 2015 paper.

Based on industry data Paul Belanger estimates the volume of steam and hot water injected into the ground at the CNRL heavy oil facility from 2020 to 2022 is 3.5 million cubic meters. It can take three barrels of steam to produce one barrel of bitumen.

In addition to the injection wells CNRL also operates five major disposal wells for wastewater and saltwater within 20 kilometres of the location of the earthquake. These wells, which dispose of waste from the bitumen wells, are much deeper (greater than 2,000 metres) than the steam injection wells.

Scientists have confirmed that fluid injection at these depths has induced seismicity in Oklahoma, Colorado, Texas, Kansas, Alberta and B.C. Moreover, these disposal wells can continue to cause earthquakes long after the injection stops.

“I suspect it will be difficult to definitively prove this seismic event [is linked] to either the in situ project or the deeper disposal wells,” Ferguson told The Tyee. “However, the physics clearly show these events are more likely as we inject fluids into the subsurface. This all seems to be a big experiment.”

Recent studies by Stanford researchers found that the injection of massive volumes of wastewater into shallow wells turned the seismically quiet Permian basin in Texas into an area plagued by hundreds of earthquakes.

The scientific literature suggests there is no upper limit to the magnitude of industry-caused earthquakes, said Allan Chapman, a former senior geologist with BC’s Oil and Gas Commission.

“The large events have a lower probability of occurring, but they are not zero probability,” said Chapman. Given the size of recent earthquakes, “larger and more damaging earthquakes cannot be discounted,” he said.

He has also called for a transparent and public investigation of the Peace River earthquakes.