Cascadia has a new bioregional journal, Cascadia Spoke. The journal is a revival of that good old medium that has graced the world with so many great journals, bioregional and other. Paper and print.

The journal is the brainchild of Brandon Letsinger, who as an organizer, promoter and entrepreneur has a lot to do with the spread of the Cascadia idea in recent years. He was pivotal in creation of the Cascadia Department of Bioregion site, which offers a comprehensive overview of the bioregional concept and its application in Cascadia, the watersheds draining into the Pacific from what is now known as Northern California to Southeast Alaska.

I’ll let Brandon tell why he came up with the idea in his own words:

“The Cascadia Spoke: A Journal of Bioregionalism was inspired by the decades of amazing maps, poetry, newsletters and publications by Planet Drum and bioregionalists around the world, especially the Raise the Stakes archive from the 1980s. (Editors’ note –Planet Drum was created by Peter Berg, one of the progenitors of the bioregional idea.) This work created a continuous archive and narrative around bioregionalism which is sorely missing from online media today.

“Like going into a bookstore or library versus ordering a book online, you don’t get just one article, but you can see the entire conversation.

“I think especially with what’s happening with Facebook, i.e. Meta, and now Twitter and Elon Musk, you can see a deep desire to get away from these corporations that are built entirely antithetical to our values and principles, run by billionaires, and who make their profit from exploiting the data of their users. People are tired of it. Of social media, of email newsletters people never see, and having to ‘pay to play’ to just even maybe get in front of audiences who want to read your content. As many of us involved in actions in the past are probably aware, so much can get lost when a website suddenly disappears. Unlike print copies, for all intents and purposes of search terms, it ceases to exist.

“We hope the Spoke can be a place where we can host real discussions, ideas, projects that can connect, empower and facilitate dialogue for Cascadia and the bioregional movement.”

As Brandon indicates, the name is a play on words, both as a connector to the larger wheel of the bioregion, and as a place where people can speak about life in Cascadia and the bioregional concept in general.

The new journal carries some classic articles carried in previous publications, including Home: A Bioregional Reader, a 1990 anthology put out by New Society Publishers, itself based in Cascadia on Vancouver Island. From the introduction to the section, “What Is Bioregionalism?,” it provides this description:

“Bioregionalism calls for human society to be more closely related to nature (hence, bio), and to be more conscious of its locale (therefore region). For humans who exhibit the most extreme alienation from nature imaginable, and who – in North America especially – are uniquely unattached to particular places, bioregionalism is essentially a recognition that today we flounder without an adequate overall philosophy of life to guide our action toward a sane alternative. It is a proposal to ground human cultures within natural systems, to get to know one’s place intimately in order to fit human communities to the Earth, not distort the Earth to our demands.”

Another article by Brandon and Lance Scott, based on a presentation by Lance at the 1988 Cascadia Bioregional Congress, “Centering Cascadia: Pacific Northwest of What?,” notes that the Northwest frame is only relevant to the lower 48 United States, “but for us, it is time to break away from this juggernaut and rethink our own relationship as citizens of our watersheds and place . . . Can we gain greater control of our common destiny at the local level? . . . Is there a way to create greater ‘connective tissue’ between various parts of our movement for change, so that we can strengthen and nourish one another?”

They conclude, “It is up to Cascadians, each in their own way, to create and promote these changes, and lead the way forward, rather than waiting for someone to do it for us.”

(A print publication also needs a good graphic designer. Lance, a veteran in the publishing field, did that work.)

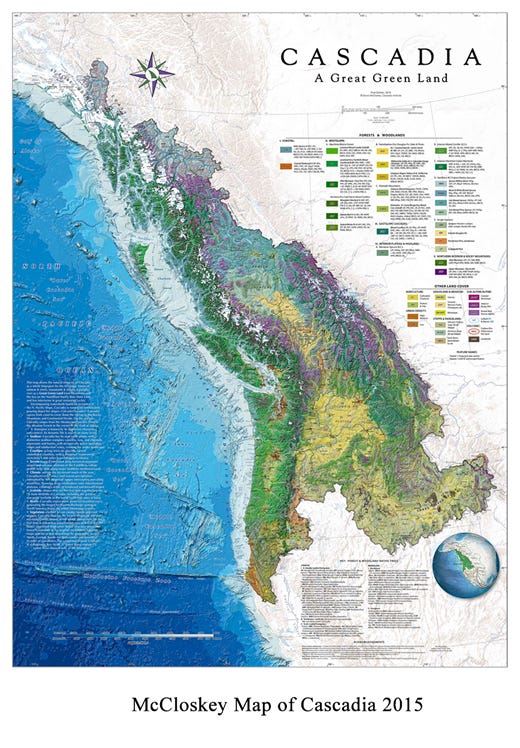

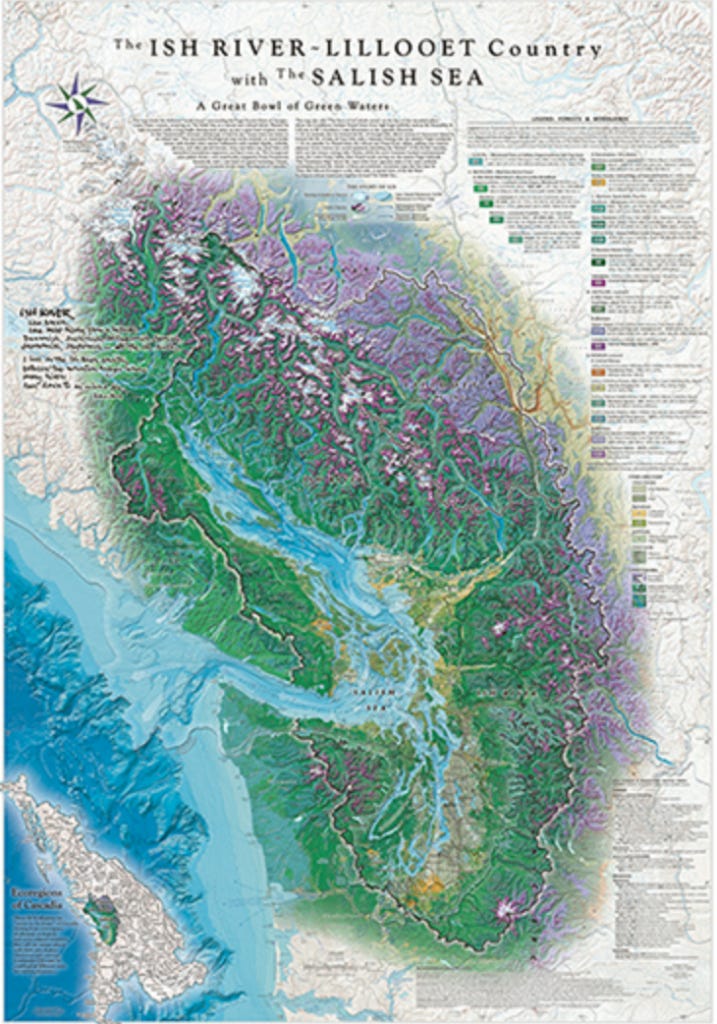

Cascadia Spoke exhibits the rich diversity of initiatives and thinking that has grown out of the concept originally elucidated by then Seattle University sociologist David McCloskey in 1981. McCloskey developed the map of Cascadia that is commonly used, and is included in the Spoke masthead. An article describes his most recent mapping project shown below, the Ish River- Country surrounding the Salish Sea, the inner waters of Cascadia hemmed by the Olympic Peninsula and Vancouver Island.

Paul Nelson, founding director of Cascadia Poetics Lab, tells of a new anthology he co-edited, Cascadian Zen, writings “that explore expressions of Zen within the Cascadia bioregion.” Another article announces the Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry to be released by Mountaineer Books in March. The guide groups species not by the normal taxonomy of birds, mammals, insects and so on, but by place-based communities such as pine forest and montane.

This edition of the biannual journal is headlined by an interview with Paul Chiyokten Wagner, a native activist who has been on the forefront of struggles from the battles against fossil fuel infrastructure to the resistance against ancient forest logging. Paul calls to the indigenous root of the bioregional idea.

“We’re all indigenous to somewhere at some point in time. I believe it’s each and everybody’s responsibility to understand that, to rekindle that, to re-indigenize themselves, and see the world again through indigenous eyes.”

Meanwhile, Jack DeVore, an Oglala-Hunkpapa-Lakota living on Vashon Island, gets down to the nub on how the region’s native people are really treated, from police killings to sexual assault in an article entitled, “What do we mean by ‘Decolonize Cascadia?”.

“Here in Cascadia, Seattle Police kill innocent Indians, and get transferred to other departments instead of being charged for the murders they commit.” Writes DeVore, “When we speak of decolonization, we speak of respect for a land and its people – and of a trust in their ability to protect and restore this bioregion for all of us who inhabit and enjoy it.”

The Spoke reveals the diversity of ideas around bioregional governance. Alexander Baretich, designer of the green, white and blue Doug Fir flag that is most commonly used – McCloskey also designed one – writes it “is neither a flag of blood nor a flag of the glory of a nation, but a love of the bioregion . . . not a “nationalistic . . . ‘we are a new country’ concept . . .”

The Doug Fir flag

At the same time, a substantial constituency exists for creating Cascadia as a new polity. Matthew Choicej writes,

“A new Cascadian state should create an economy based on local human relationships, not on the abstractions of economic theory. Small businesses, worker-owned coops and employee stock ownership come to mind. However, most important, a Cascadia economy should be local . . . an economy largely removed from the vicissitudes of international capital.”

Producing locally is also the theme of an article by Austin Donofrio, “Decentralization of Needs.” Michael Caster focuses “The Case for a Human Rights Bioregion” guaranteeing the broad range of civil, political and economic rights.

Jeffree Mocniak, who describes himself as an inhabitant of the Wind River Valley, calls for building empathy by coming together in communities built around watershed councils. Ian Gill writes of the Salmon Nation initiative, covering the turf where Pacific salmon return to spawn. My own article seeking to draw together cultural regions centered around cities with bioregions centered on nature, “Finding a Place to Make a Stand”, previously published in The Raven, is also included.

That and more make up this first, winter solstice edition of Cascadia Spoke. The next is due out at the June summer solstice. Copies of the first edition are still available. To receive a copy by mail, sign up here. But hurry. The first run was only 2,000 copies.

This edition is supported by a grant from King County 4Culture. Cascadia Department of Bioregion is seeking 40 supporters to donate $10 a month to sustain future press runs of 2,000. People who would like to help, contribute, or sign up to distribute a bundle can do so here.

Online PDF’s of the Spoke will be hosted on that website, and individual articles will be hosted on the Cascadia Underground.

Studies have shown that the experience of reading print books and e-books is entirely different, and I found this also true with publications. I enjoyed the physical touch of turning pages and, as Brandon notes, seeing how the articles all flow together. Cascadia Spoke is a worthy addition to the growing Cascadia culture, and a model for people seeking to grow the cultures of their own bioregions. May we see many more editions, and similar journals pop up elsewhere.

This article was originally published in The Raven, https://theraven.substack.com/