An economy is a system of production and consumption activities connected via allocation mechanisms. Simply, it is how people produce items and services that other people later consume. Economies are also inextricably entwined with the wider spheres of life bearing on political, communal, kinship, and ecological relations. For those who dislike or even detest capitalism and all of its societal effects, what better economy can we seek? Is there a better alternative?

We propose the following set of five features, based on the values of self-management, equity, solidarity, diversity, and sustainability, as a foundational framework for a good economy for all, an economic vision known as participatory economics. This presentation is intentionally brief and should engender more questions than it gives answers. It should inspire further engagement towards an economic vision that seeks to achieve human fulfillment and wellbeing within ecological bounds.

Who Owns What?

In any economy, workers use equipment, resources, venues, and diverse skills and knowledge that have accumulated over years, decades, and centuries to produce items and services. In capitalism, these “means of production” are overwhelmingly owned by roughly two percent of the population. We call them capitalists. They include Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, and Warren Buffett. Capitalists are human, of course, but they occupy inhumane roles. Countless books, essays, videos, etc illuminate all the ways that private ownership of productive assets has been and continues to be destructive, so we will not elaborate on that here. Instead, we will move on from what we reject, to what we want. A worthy post-capitalist means of production should compose a Productive Commons, that no one owns but that people utilize, to produce outputs which they and others later consume. Inhumane economic roles and their associated outcomes should be replaced.

Capitalists currently decide workplace production. Without capitalists, who will run workplaces? Without Bezos, who will run Amazon? We propose, why not Amazon’s workers and consumers?

Who Decides What?

Where will workers gather to make decisions about what their workplaces and industries produce and about how workers, in teams and individually, do the producing? And where will consumers gather to make decisions about their personal consumption (shoes, ice cream…), their living unit consumption (couches, homes…), their neighborhood and city consumption (subways, schools…), and even their state and whole society consumption (pandemic prevention, highways…)?

We propose that sometimes people will make production decisions individually or in work teams. Sometimes people will make consumption decisions individually or in families or other local groups.

But what about larger scale decisions whether for workplaces or industries, or for neighborhoods, cities, or states?

People will need to make those decisions collectively as members of what we call “workers and consumers councils” and “federations of councils”.

To make their decisions, will workers and consumers use consensus, or majority rules, or some other method? And is it really all of them who will decide?

We propose, sometimes workers and consumers will use consensus, sometimes they will use one person one vote, majority rules, and sometimes they will use other means of deliberation, voting, and tallying.

Why not always use one preferred optimal way?

Because the councils exist to seek self management, by which we mean that all people should have a say in decisions in proportion as they are affected by them. The exact forms of deliberation, voting, and tallying that councils opt for regarding different decisions are just various tactics councils might choose so as to self manage.

Self management is best achieved in diverse contexts via diverse means. Workers and consumers are all affected by acts of production and consumption, but not all to the same extent in every situation. Therefore, all workers and consumers should have a say regarding outcomes, but at different times, in different places, and for different issues, sometimes decisions should be private, sometimes collective. When collective, sometimes one approach is best for attaining self management, while sometimes another approach is best – again, methods of deliberation, voting, and tallying are a set of tactics and tools for achieving self management. Different approaches can accommodate different impact on different participants. For example, at work, I decide what I wear, our work team decides our team’s internal operations, the whole workplace council decides overall policies.

Self managed councils are the second feature, after a productive commons, that we propose as a set of defining features for a good post capitalist economy.

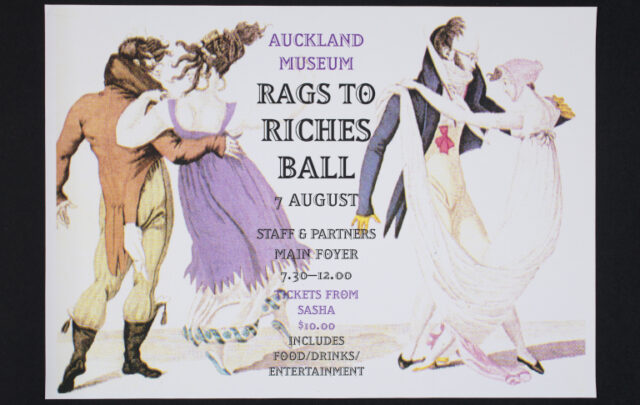

Image from the ‘Dear Alice’ Decommodified Edition by Waffle to the Left

Who Does What?

If workers and consumers are to decide economic procedures and outcomes, they will need to wisely consider diverse matters. If not, bad decisions will hurt everyone. What will ensure that workers and consumers are wise decision makers?

To start, what prevents everyone from being wise decision makers in diverse situations now? Partly, it is a lack of training before going into work in the first place. This would need to change. But there is another more revealing and instructive factor. All economies necessarily combine bunches of tasks into jobs that people do. But how do economies pick which tasks to bunch together into which jobs? That is where issues arise. In current workplaces we have what we call a hierarchical or “corporate division of labor.”

Utilizing the corporate division of labor, economies combine “empowering tasks” into one set of jobs such as high level manager, accountant, lawyer, professor, doctor, engineer, and so on. Simultaneously, economies combine “disempowering tasks” into another set of jobs such as factory assembler, short order cook, nursing home and hospital staff, automotive repair, delivery services, garbage collector, and so on. An economy’s empowering jobs convey to managers, accountants, and others who do them decision making skills, knowledge, access, confidence, ties to others, and readiness and energy essential to making workplace decisions. An economy’s disempowering jobs reduce the decision making skills, knowledge, access, confidence, ties to others, and readiness and energy essential to making workplace decisions of assemblers, drivers, and others who do them.

To prepare us for the corporate division of labor even before entering the workforce, our education provides what the economy needs. Our education prepares twenty percent of us to expect to fill coordinator roles, and prepares eighty percent of us to expect to take orders and endure boredom.

There is undeniably a fuzzy borderline, but we call employees who are made ready and willing decision-makers by their doing empowering jobs the “coordinator class”. We call employees who are distanced from and unprepared for decision-making by their doing disempowering jobs the “working class”. By virtue of their empowering circumstances, the former, roughly twenty percent, coordinators dominate the latter, roughly eighty percent, workers. The coordinators determine agendas, hash out policies, and determine outcomes. They give orders. The workers hear about outcomes and implement decisions others make. They follow orders. This dynamic can occur with the ruling capitalist class situated above both coordinators and workers, as happens in capitalism. It can also occur when the coordinator class occupies the top spot, due to capitalist ownership having been eliminated but the corporate division of labor having been maintained, as has happened in various iterations of twentieth century socialism.

Does this division of labor obstruct self management?

Yes, even with a productive commons and even with workers and consumers councils, if a new economy retains the familiar corporate division of labor, the composition of its jobs will preclude roughly eighty percent of employees from being prepared and ready to decide outcomes. A retained corporate division of labor will ensure that only twenty percent of employees decide outcomes. Under capitalism, this coordinator class resides between labor and capital. With capitalists gone, the corporate division of labor, as we have seen historically in twentieth century socialism (better named coordinatorism) and even in non-profit businesses inside capitalist economies, elevates the coordinator class to become a new ruling class.

Does that mean hope for self management for all is an unattainable dream? Does it mean that to have viable production and consumption, we must have a coordinator class above and a working class below? Coordinators empowered and enriched? Workers disempowered and impoverished? Is it inevitable that among humans, a few will order and the rest obey?

No. But it does mean that to get rid of class rule we not only have to eliminate private ownership to end rule by rich owners, we also have to eliminate the corporate division of labor to end rule by empowered coordinators. We need to complete our effort to eliminate systemically produced class division. In other words, to foster self management we must consider not just who owns what, but also who does what, in order to equitably empower all to participate in who decides what.

Balanced Work

The intention seems admirable, but first and foremost we have to get stuff done. If eliminating the corporate division of labor means we self manage chaos and endure poverty, most people would rightly vote to maintain what we have.

Fair enough. And that means we need to get rid of the corporate division of labor but nonetheless produce and consume wiser and better. No chaos. No poverty. Our desire to eliminate class hierarchy means we have to get rid of a skewed distribution of empowering tasks. To achieve that, instead of having only about twenty percent of employees do all the empowering tasks, we propose to combine tasks into jobs so that every job is comparably empowering as all others. Each job has some empowering and some disempowering aspects in a balanced mix that roughly equalizes the empowerment effects of all jobs. These “balanced job complexes” remove the basis for there being coordinators above and workers below.

All workers and consumers make decisions in their councils. They are empowered to do so by prior training and by doing a fair share of empowering tasks. It sounds good, but is it viable? Won’t it underutilize surgeons, for example, by having them spend some time cleaning up? And can everyone who now cleans up do balanced work well?

Consider an example. If Joe can do thirty or more hours of surgery (or accounting, or managing, or whatever) but in his balanced job he could only do, say, fifteen or twenty hours of surgery (or accounting, or managing, or whatever) because he also has to do other less empowering tasks, then with such a proposed change, it is true that we would get less total worth of surgery output from Joe. More, one in five employees in current economies are like Joe, responsible for a monopoly of empowering tasks. So, if we would lose a percentage of valuable output from these folks, why change?

Because for the other four out of five employees, this change liberates their current unused potentials. This change liberates more than enough gain to offset the loss. Plus, and this is the primary motivation, with this change we also end class rule. We end robbing four fifths of employees of dignity and efficacy. We end elevating one fifth of employees above to dominate four fifths below. We get more overall productive potential and creative capacity from our society, and better still, we get more self management, a greater diversity of thought and practice, and more solidarity and dignity for all. This change results in a huge net benefit.

Still not sure if this is viable? What makes advocates of participatory economics believe the four fifths will have sufficient talents and capacities liberated by this job balancing, even with improved schooling, to offset potential losses due to others not fully exercising their talents due to their having to do some disempowering, as opposed to only empowering, tasks?

Fifty years ago, medical schools and law schools in the U.S. were overwhelmingly male and white. The common belief/rationale to explain that was that it was because women and people of color were unable to be productive doctors and lawyers. Someone hearing about the overwhelming white male preponderance could think: Others don’t become doctors or lawyers. Obvious explanation, others can’t heal the sick or practice law. That explanation would have indeed been correct for some people, because of course, not everyone is suited or inclined to be a doctor or lawyer. But there was another, better explanation. People of color and women, writ large, didn’t become doctors, lawyers, scientists, managers, and so on, not because of some kind of underlying intrinsic incapacity, but because social arrangements reduced and denied their capacities, as well as excluded them. Everyone should have easily discerned that was the case, yet many, indeed most, did not discern it was the case. Even many (of the few) people of color and female doctors and lawyers, much less most of the great many white male doctors, lawyers, scientists, and managers often thought the issue was capacity, not subjugation. What prevented many people from seeing what should have been obvious? Pervasive sexism and racism.

Flash forward fifty years, working class people do not do empowering jobs. Someone might say, Jim or Sue can’t do surgery or write a legal brief because workers can’t do empowering tasks. In our society, about 80% of the population is channelled, often by home life, certainly by training, and then on the job, to take orders and endure boredom. Just as progress towards overcoming racism and sexism has led to people of color and women thriving as lawyers, doctors and in diverse empowering pursuits, so will overcoming what we might reasonably call classism lead to the 80% becoming more than able to do their share of empowering tasks in balanced jobs.

Therefore, we propose balanced job complexes as the third feature of a desirable post-capitalist economy. Yes, we will lose some productivity and innovation that we could have gotten from 20% of employees doing only empowering tasks. On the other hand, we will gain classlessness and all the dignity and solidarity that will mean. And we will also gain the productivity, diversity, and innovation freed by 80% of employees developing and utilizing their capacities rather than succumbing to the dictates of a corporate division of labor.

Image from the ‘Dear Alice’ Decommodified Edition by Waffle to the Left

Who Gets What?

Even supposing balanced jobs would be viable, how do we determine who gets what? In capitalism, not only do owners get more than workers, but so do coordinators. What determines income in this new way of conducting economics?

We have already proposed to remove private ownership of productive assets. With no owners of means of production, there are no profits. We now propose to also do away with income for power. That is, we don’t want people to get what they have the power to take. Enrichment of thugs and bullies is not worthy economics.

More controversially, we don’t think people should be rewarded for luck. To be lucky enough to have better tools or more productive workmates, or even to have greater than average inborn talents, shouldn’t mean you get greater income.

Instead, we propose that people not only work at balanced jobs, but that they also receive income only for how long they work, for how hard they work, and for the onerousness of the conditions of their work, as long as their work produces socially valued outputs. Those who cannot work would receive the social average income. People would get more (or less) than the social average, only because they work longer (or less long), harder (or less hard), or under worse (or better) conditions producing valued output. This approach rewards, and therefore provides an incentive for, what people actually do. It provides one fair norm for everyone.

What about incentives? Will people undertake the education necessary to learn to do surgery or other empowering tasks without the prospect of receiving vastly more than merely equitable income?

We are always told, no, they would not. But suppose everyone receives early education to utilize their capacities fully and everyone grows up with ample familial income. You finish the new kind of high school and it is time to choose where to work. Do you want to pursue further learning, right up through med school, or whatever path fits your preferences and abilities, so that you can thereafter exercise all your capacities and desires? Or do you want to forego more learning to begin work without fully developing your capacities in directions you choose because doing so won’t entitle you to an unjustly elevated income? It is hard to imagine anyone answering that they wouldn’t prefer to fulfill their talents, even if they and everyone got equitable, rather than exploitative, income for doing so.

We therefore propose an equitable remuneration norm, based on duration, intensity and onerousness for socially valued labor, as the fourth feature of a desirable post-capitalist economy.

How does Allocation Occur?

We have addressed much about proposed features of a new economy beyond capitalism, albeit without the depth to address full criticisms and explore all consequences. But there is still a big issue to deal with, even to arrive at a summary, much less to assess the description to discern additional implications and determine viability and merit – how does allocation occur? Workers produce. Consumers consume. How does what is produced match up with what is sought for consumption? Can an economy allocate well and at the same time foster and serve the proposed productive commons, council self management, balanced jobs, and equitable remuneration? Would not the inherent, destructive greed of markets and the inherent authoritarianism of central planning each subvert those other aims?

Yes, they would horribly interfere, and for that reason, just as we have to propose a viable and worthy alternative to private ownership of productive assets, to top down decision making, to the corporate division of labor, and to remuneration for property, power, or even output, to complete our list of core features of a desirable post capitalism, we also have to propose an alternative to markets and to central planning. Otherwise, retaining either markets or central planning, or both in some mix, would subvert the other proposed new features.

In organizing allocation, we don’t want to systemically encourage and reproduce competition that breeds the worst kind of me-first, rat race behavior. We instead want allocation that generates solidarity and even empathy. We don’t want allocation that misvalues economic effects like pollution or that biases against public goods. We don’t want allocation that pressures for growth for the sake of growth itself, even at the expense of human and ecological wellbeing. We want allocation that properly accounts personal, social, and ecological consequences of economic choices. We don’t want top down commands. We want self management. Based on these and a good many more criticisms of both markets and central planning, and on the positive desire to further rather than subvert a productive commons, self managing councils, balanced jobs, and equitable remuneration, we propose a fifth feature, called “participatory planning”, for allocation.

Participatory Planning

Workers and consumers, via their councils, propose their desires for their work and their consumption. Workers’ proposals seek to utilize productive assets socially responsibly so that outputs are produced without waste or incompetence and are all socially desired. Consumers seek to enjoy a share of social product consistent with their expected income, so that their request is socially just. Proposals from workers and consumers are processed to generate updated estimates of likely prices, and to also indicate if items are in over or under supply.

Councils then make new proposals, in light of the updated information. Each round of making proposals is called a “planning iteration” and in each new iteration, supply and demand converge as estimated prices approach true final prices. Finally, after five to seven iterations, a plan is reached. Additional features of the process facilitate properly pricing pollution and other ecological and social effects, as well as conducting long term planning.

Participatory planning has no top or bottom. It has no center or periphery. There is no command and no obedience. Instead, workers and consumers have an appropriate, self managing say in an iterative process consistent with, abetted by, and aiding the other four features of the economy. Via participatory planning, self managed councils arrive at outcomes that advance well being and development and deliver equitable incomes for all.

Image from the ‘Dear Alice’ Decommodified Edition by Waffle to the Left

Filling Out the Framework & Going Beyond Economics

So is that it? Five features and we have post-capitalism?

Not quite. Rather, we have a kind of scaffold of what we propose as necessary elements for a post-capitalist economy to successfully implement self management, attain equity, produce solidarity, honor diversity, and facilitate sustainability and internationalism, all while avoiding waste and producing and consuming in pursuit of fulfillment and development. To get a full working post-capitalist economy however, future citizens will have to add to its essential scaffold many contextual, contingent details and policies based on their own future economic situations, experiences, lessons and desires.

What about racism, sexism, ableism, and other impingements on and denials of people’s life prospects? Does participatory economics address those profound, priority problems?

Yes, in two powerful ways. First, a successful operational participatory economy has the same norms for everyone. All who work have a balanced job. All who work or consume have self managing say. All who work receive income for the duration, intensity, and onerousness of their socially productive efforts. All who can’t work get a socially average income. There is no workplace hierarchy of power or circumstance. Income only varies in accord with equity. There is no economic hierarchy for race, gender, or anything else.

Second, to be successful in a whole society, participatory economics will have to abide and abet requirements emanating from intersecting, overlapping political, kinship, cultural, ecological, and international transformations, just as those other realms, also revolutionized in a future participatory society, will have to abide and abet intersecting, overlapping economic requirements. The point is, society has various intersecting and overlapping realms. Each needs to be transformed to eliminate the sources of its own unjust hierarchies. Each also needs to accommodate and even aid the transformations of other realms.

Further Scrutiny, Development, and Advocacy

Is the above summary fully convincing? Not really. Or at least it shouldn’t be. Not yet. It certainly claims admirable things. But it doesn’t fully address diverse reasonable concerns people may have.

Is the above summary enough to elicit further interest? Is it enough to motivate you, dear reader, to look more closely at this economic vision, called participatory economics, to determine if, after critical viewing, it rings both feasible and worthy? We hope so.

We hope that learning there exists a proposed post-capitalist economic vision that claims to foster self management, equity, solidarity, diversity, sustainability, and socially beneficial efficiency, and that claims to eliminate class division and to support feminist, anti racist, and anti authoritarian gains throughout society, you will want to consider it more closely to see if its claims are valid.

There are many further resources in the form of books, websites, networks, and projects. Perhaps most accessible to a wide audience are the recent book by Michael Albert, No Bosses, A New Economy for A Better World, or the recent book by Robin Hahnel, A Participatory Economy. Online, RealUtopia.org is an international network for activists, advocates, and anyone interested in learning and engaging. ParticipatoryEconomy.org is an educational website and think tank. The newly renovated ZNetwork.org has decades of articles, debates, links to books, websites, videos, projects, daily updates, and a new community forum. The concepts of participatory economics may be considered outside the box, but they are by no means out of reach.

Finally, what’s the use of learning about and engaging with all this visionary thinking? We all know that we live in a broken economic system that is now actually breaking the planet itself. We must begin to take seriously the question, what’s next? If our aim is for our economy to elevate, as opposed to decimate, our highest values, the status quo has failed and will continue to fail. If our aim is at minimum to sustain the possibility of our continued existence on earth as a species, let alone to pursue ecological reciprocity and balance, our current economic system has and will continue to fail. The question is no longer whether we should change, the question is how and with what aims.

The logic couldn’t be more simple, we can and must envision the better world we seek in order to have any hope of pursuing and building it. Carving that path begins with envisioning the answers to the question, “what do you want?”, and continuously assessing, developing, and advancing that vision along the way to achieving it.