Fossil fuel use will peak within five years, says the World Energy Outlook 2022 from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The 524-page outlook says the global energy crisis and Russia’s war have “turbo-charged” the shift away from fossil fuels.

For the first time, coal, oil and gas will each peak, even if countries fail to meet their climate pledges. The report says this will be a “pivotal moment” in history.

The findings pour cold water on “mistaken and misleading” ideas around the global energy crisis. IEA executive director Dr Fatih Birol says the “clean energy transition” is the “best way out” of the crisis. This can be a “historic turning point” for climate action, he adds, rather than a setback.

Countries are moving to electrify heat and transport more quickly than they were last year, the IEA says. It adds that “clean energy…is the big growth story of this outlook”.

Global energy demand growth will “almost entirely” be met by renewables. Moreover, global solar capacity will climb 18% higher by 2030 than expected last year – and wind 14%.

Global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are now set to peak by 2025 at the latest, the outlook says. As a result, the world would warm by 2.5C this century, slightly less than the 2.6C the IEA expected last year.

Countries have also boosted the ambition of their climate pledges. These would now limit warming to 1.7C if met in full, rather than 2.1C stated last year.

However, it is “easier to make pledges than to implement them”, the IEA says. There is still a “long way to go” to align action with the 1.5C target.

The outlook also raises concerns over rising geopolitical tensions and millions of people losing access to energy due to fossil fuel price inflation. It says the shift away from the “fragil[e] and unsustainab[le]” energy system built on fossil fuels calls for new approaches to energy security.

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of previous IEA world energy outlooks from 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 and 2015.)

World energy outlook

The IEA’s annual World Energy Outlook (WEO) is published every autumn. It is widely regarded as one of the most influential annual contributions to the climate and energy debate.

The outlook explores a range of scenarios, representing different possible futures for the global energy system. These are developed using the IEA’s “Global Energy and Climate Model”.

The 1.5C-compatible “net-zero emissions by 2050” (NZE) scenario, introduced last year, is now firmly established in the mix. This scenario shows a “narrow but achievable” route to the 1.5C target.

The NZE takes its place alongside the “stated policies scenario” (STEPS), representing “current policy settings”. For this scenario, the IEA “do[es] not assume that…targets are met unless…backed up with detail on how they are to be achieved”.

In the “announced pledges scenario” (APS), the IEA gives governments “the benefit of the doubt”. All pledges, no matter how aspirational, are assumed to be met on time and in full.

Annex B of the report breaks down the policies and targets included in each scenario. In effect, the IEA is judging the seriousness of each target and whether it will be followed through.

For example, the provisions of the recently legislated US Inflation Reduction Act are included in the STEPS. But the US target to cut emissions to 50-52% below 2005 levels by 2030 is only met under the APS.

For the EU, new coal phaseout commitments and updated national energy and climate plans are in STEPS. Full implementation of the RePowerEU package, however, is only in the APS.

In the same way, China’s 14th five-year plan and India’s renewable targets are within STEPS. Their long-term targets to become carbon neutral by 2060 and 2070, respectively, are in the APS.

One corollary of this is that the STEPS is all but guaranteed to include stronger policy next year. This increase in ambition over time, as announced pledges are converted into stated policies, is clear from the historical record. (See below for charts comparing IEA outlooks over time.)

The NZE was at the heart of last year’s outlook, mentioned much more frequently than the other scenarios. This year, the STEPS retakes a central position in the report. It is mentioned 180 times per 100 pages, compared with 173 for APS and 155 for NZE.

Similarly, this year’s outlook only mentions “1.5C” half as often as last year. In contrast, the report mentions “Russia” 78 times per 100 pages, nearly five times more often than in 2021. Other more frequent words include “crisis” (35 times per 100 pages, up from 4) and “inflation” (14, up from 1).

Global energy crisis

The shift in emphasis in this year’s outlook comes for obvious reasons. The world is in its “first truly global energy crisis”, with “profound” impacts that will reverberate for decades.

The IEA says the crisis was “triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine”. While markets were already straining last year, Russia tipped what was a strong recovery from the pandemic…into full-blown turmoil”. It adds that Europe’s reliance on Russian energy was a “strategic weakness”.

Birol uses his foreword to give short shrift to those that seek to put the blame elsewhere:

“[T]here is a mistaken idea that this is somehow a clean energy crisis. That is simply not true…When people misleading blame climate and clean energy for today’s crisis, what they are doing – whether they mean to or not – is shifting attention away from the real cause: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.”

The report says there is “scant evidence” that investment in fossil fuel supplies was “stifled” by net-zero targets. It is also “difficult to argue” that climate policies had a role in high energy prices.

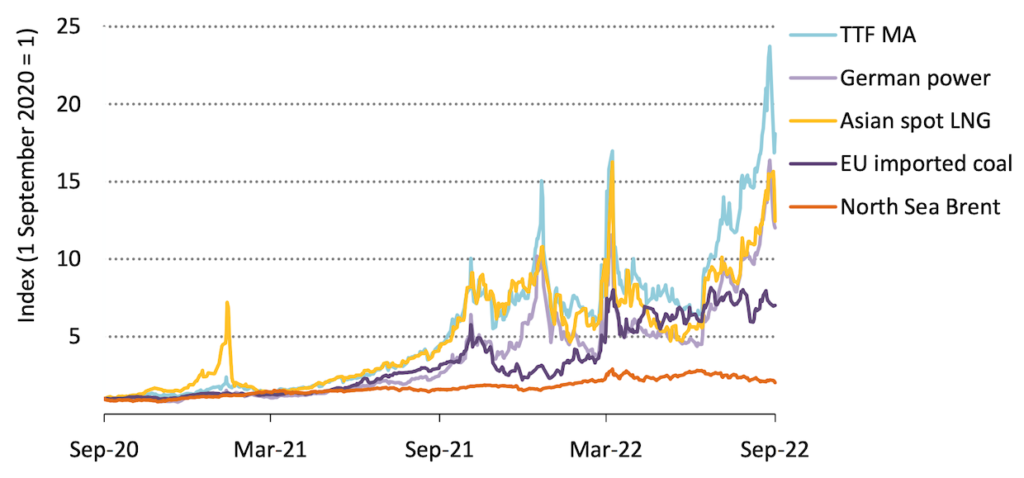

Indeed, the IEA says high gas and coal prices are behind 90% of the increase in global electricity prices this year. By September 2022, the TTF European gas benchmark reached 24 times its price two years earlier, as shown in the chart below.

Selected energy price indicators, shown relative to September 2020 levels. TTF MA is the month-ahead benchmark price for gas in Europe. North Sea Brent is a benchmark price for crude oil. LNG is liquified natural gas. Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2022.

Periods of high fossil fuel prices “offer strong incentives to move away from reliance on these fuels or to use them more efficiently, reinforcing the momentum behind energy transitions”, the IEA says. It could also “spur renewed investments in fossil fuel supply” in the name of energy security.

The balance between these two outcomes is a key choice for governments that could help – or hinder – hopes of keeping warming below internationally agreed targets.

The short-term response has seen governments commit “well over $500bn” to protect consumers. They have also “rushed to try to secure alternative fuel supplies”, allowed higher use of coal power, extended nuclear plant lifetimes and accelerated renewable projects, the IEA says.

Despite fears of a coal “comeback”, however, the IEA says “the upside for coal from today’s crisis is temporary”. Nor will it lead to higher investment in coal-fired power plants.

Indeed, the IEA says that three-quarters of the additional energy-related investment in 2022, relative to last year, “is being drawn towards clean energy”.

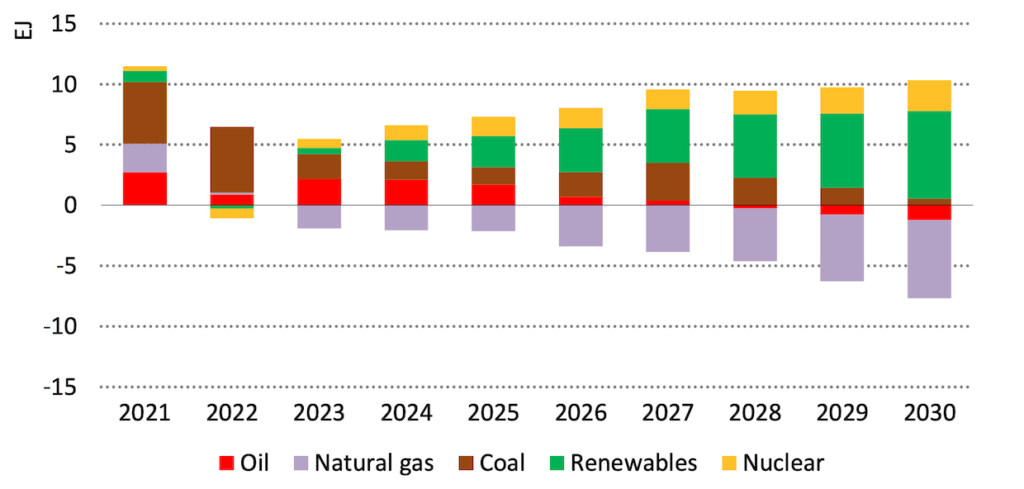

By 2030, coal use will be at similar levels to those expected last year (brown bars, below). Crucially, coal still faces “structural decline” from the mid-2020s, the IEA adds.

For each year, the bars show whether global demand for each fuel will be higher or lower than expected in 2021, in exajoules. Coal (brown) and oil (red) see short-term gains while renewables (green) and nuclear (yellow) see stronger growth in the medium term. Gas (lilac) is squeezed in all future years. Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2022.

The chart above also shows the impact of medium- and longer-term responses to the crisis. Policy responses are “fast-tracking the emergence of a clean-energy economy”, the IEA says.

It says many governments are “looking to accelerate structural change” in their energy systems. It gives examples including the US Inflation Reduction Act, the REPower EU plan, Japan’s Green Transformation (GX) programme and South Korea’s targets to boost nuclear and renewables.

Similarly, the “massive build-out of clean energy in China” will cause a peak in coal and oil use before 2030. And renewables will meet two-thirds of India’s growth in electricity demand.

Overall, the outlook says “the lasting gains from the crisis accrue to low-emissions sources, mainly renewables” as well as “faster progress with efficiency and electrification”.

(The outlook says: “Demand-side measures have generally received less attention, but greater energy efficiency is an essential part of the short- and longer-term response.”)

These gains mean that, for the first time, the IEA now expects fossil fuel use to peak and then decline. Its outlook points to a peak in total fossil fuel around 2027 – in just five years.

The report explains just how big a moment this decoupling will be for the world:

“Global fossil fuel use has risen alongside GDP since the start of the industrial revolution in the 18th century: putting this rise into reverse while continuing to expand the global economy will be a pivotal moment in energy history.”

This moment is the culmination of a series of shifts in the outlook for fossil fuels, shown in the chart below.

Before the Paris Agreement in 2015, the IEA expected fossil fuels to continue their historical march upwards (grey line). That growth has been steadily eroded (blue lines), as shifts in government policy, technological progress – and now Russia’s war – have boosted clean energy.

Black line: Historical global demand for fossil fuels, exajoules. Grey and blue lines: The shifting outlook for fossil fuel growth as policies have evolved since before Paris. Pink and red lines: The impact of meeting new climate pledges made since last year. Yellow lines: What would happen if the world was on a path to staying below 1.5C. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of IEA World Energy Outlooks. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

The fossil-fuel peak is “emblematic of a shift in the energy landscape since the Paris Agreement”, the IEA says. After meeting 80% of global energy demand for decades, policies in place today will ensure fossil fuels fall to 75% by 2030 and to 60% by 2050.

(The red line in the chart above indicates that the decline in fossil fuels will be even faster if countries meet their climate pledges. See: Narrow pathway for 1.5C.)

The IEA says for the first time its outlook includes separate peaks for coal (“within the next few years”), oil (“in the mid-2030s”) and gas (“by the end of the decade”).

The most dramatic change in fortunes since last year is for gas. Last year, gas demand was expected to grow 20% by 2050. Now the figure is just 2%, with 89% of expected growth wiped out.

The “golden age of gas” predicted by the agency in 2012 has been “undercut” by the current crisis. Growth has all but evaporated and the “golden age” has come to an end.

(Box 8.3 on page 407 of the report asks rhetorically if the golden age is over. Elsewhere, it says Russia’s actions mean the “era of rapid growth in natural gas demand draws to a close”.)

While high fossil fuel prices have delivered a “huge” $2tn windfall for fossil fuel producers, including Russia, at the expense of importers such as Europe, the longer term story is different.

By invading Ukraine and precipitating a global energy crisis, Russia has lost its largest export market in Europe. It faces a “much diminished role in international energy affairs” and there are “considerable doubts” over a pivot to Asia because of physical supply constraints.

Russia’s share of global fossil fuel exports will fall precipitously, particularly relative to pre-war expectations. It is set to lose out on more than $1tn in export revenues this decade.

Russia faces the prospect of a much‐diminished role in international energy affairs without its largest export market in Europe. Its set to lose out on more than USD 1 trillion in export revenues over this rest of this decade. #WEO22 pic.twitter.com/uZ4J4cXm4U

— Christophe McGlade (@TofMcGlade) October 27, 2022

Although Russia’s actions have “sever[ed] one of the main arteries of global energy trade”, the IEA cautions against investment in new fossil fuel supplies.

First, new supplies take years to come onstream and “are unlikely to provide any relief in the short term”. It says conventional oil and gas projects starting production since 2010 have taken an average of 19 years from the award of an exploration licence through to first production. Extended production from existing fields is a “better candidate” for making up any shortfalls, it says.

Second, new supplies would generate CO2 emissions that would need to be compensated later on, creating a “clear risk” that the 1.5C target “moves out of reach”. The report says:

“[E]missions coming from new projects…do not come for free in climate terms…No one should imagine that Russia’s invasion can justify a wave of new oil and gas infrastructure in a world that wants to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.”

Instead, the report says “clean energy transitions…represent the best way out of [the crisis]”. Renewable sources remain the cheapest option for new electricity generation in many countries, it says, “even before taking account of the exceptionally high prices seen in 2022 for coal and gas”.

Higher investment in renewables would “help[] to reduce electricity costs as well as emissions”, it says. And “energy security concerns reinforce the rise of low-emissions sources and efficiency”.

Though the outlook does not say so explicitly, the implication is that the fabled “energy trilemma” is being solved by clean energy. It explains:

“The environmental case for clean energy needed no reinforcement, but the economic arguments in favour of cost-competitive and affordable clean technologies are now stronger – and so too is the energy security case. This alignment of economic, climate and security priorities has already started to move the dial towards a better outcome for the world’s people and for the planet.”

As a result of this alignment between objectives, Birol pushes back on the idea that the crisis will be a setback for climate action. He writes in his foreword:

“Another mistaken idea is that today’s crisis is a huge setback for efforts to tackle climate change…In fact, this can be a historic turning point towards a cleaner and more secure energy system.”

Narrow pathway for 1.5C

In some areas, the world is already making rapid progress. The IEA says that global energy demand growth through the rest of the decade will “almost entirely” be met by renewables.

The growth of wind and solar is once again set to surpass previous expectations. The IEA has raised its outlook for solar capacity growth to 2050 by 21% since last year. This is shown in the chart below as the difference between the red and dark pink lines.

Instead of the 6,163 gigawatts (GW) by 2050 expected last year, global solar capacity is now due to reach 7,464GW under today’s policy settings, the IEA says. This is more than five times higher than the 1,405GW expected by 2050 under pre-Paris policy (light pink). Indeed, the world is due to pass the IEA’s 2015 outlook for 2040 of 1,066GW some time this year.

The chart also shows how the outlook for global wind capacity 2050 has surged, from 1,738GW before Paris to 2,995GW last year and 3,564GW this year, an increase of 19% since 2021 alone.

IEA outlook for global wind (blue) and solar (red) capacity, gigawatts, under stated policies before Paris, in 2021 and this year. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of IEA outlooks. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Current wind and solar growth rates are faster than required under stated policies (STEPS) and there are signs of rapid progress elsewhere, the outlook says:

“Today’s growth rates for deployment of solar PV, wind, EVs and batteries, if maintained, would lead to a much faster transformation than projected in the STEPS, although this would require supportive policies not just in the leading markets for these technologies but across the world.”

Moreover, current growth is sufficient to ensure that electricity supplies from fossil fuels will shrink. The report says: “The increase in renewable electricity generation is sufficiently fast to outpace growth in total electricity generation, driving down the contribution of fossil fuels.”

It adds that the potential for faster progress “is enormous if strong action is taken immediately”. This would require, for example, “expanded and modernised grids”.

The report also looks at the manufacturing capacity needed for key clean-energy technology supply chains. It finds that for solar, batteries and the electrolysers needed to make low-carbon hydrogen, enough capacity is built or planned by 2030 to meet current climate pledges.

However, for heat pumps, lithium and copper, there is a shortfall relative to what will be needed.

This is shown in the figure below, which compares current capacity (dark green), the announced pipeline (light green) and the excess (hatched green) or shortfall (hatched red) in capacity by 2030, relative to that needed to meet climate pledges in the APS.

Current and announced manufacturing capacity for key clean energy technology supply chains, relative to the levels needed in the APS. Source: World Energy Outlook 2022.

(Box 3.6 of the report compares the size of these supply chains to what would be required by 2030 under the 1.5C-compliant NZE scenario. It finds that only solar has enough capacity planned.)

These clean-energy supply chains are a “huge source” of employment growth, the IEA notes. It adds that there are already more clean-energy jobs globally than there are in fossil fuels.

The rapid progress of some clean-energy technologies and the coming peak in fossil fuel demand mean that global energy-related CO2 emissions will peak by 2025 at the latest, the IEA says.

The decline in fossil fuel use under today’s policy settings would see emissions dropping from 37bn tonnes (GtCO2) in 2021 to 36GtCO2 in 2030 (-1%) and to 32GtCO2 (-13%) by 2050.

These emissions in the STEPS correspond to warming of around 2.5C this century. This improves on the 3.5C of warming expected under stated policies before Paris, as shown in the chart below. Nevertheless, it remains “far from enough to avoid severe impacts from a changing climate”.

Left: Global energy-related CO2 emissions, billions of tonnes, in the IEA’s pre-Paris outlook (red) and in this year’s STEPS (blue), APS (yellow) and NZE (green). Right: Corresponding warming expected in 2100. Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2022.

The 2.5C of warming under today’s policy settings is a slight improvement of 0.1C on what was expected last year. There has been a much larger improvement in the ambition of the world’s climate pledges, shown by the yellow “APS” line in the chart above.

Whereas pledges announced ahead of last year’s outlook were enough to limit warming to 2.1C, new pledges over the past 12 months push that down to 1.7C by 2100. The most significant factors in this shift are new net-zero pledges from India (2070) and Indonesia (2060).

(This year, for the first time, the IEA includes industry- and company-level targets in its APS.)

To meet their climate pledges, countries will need to close what the IEA calls the “implementation gap”. This is the gap between current policies and the action needed to meet their goals.

Despite the increase in ambition over the past year, a large “ambition gap” remains between current pledges and the IEA’s pathway to the 1.5C target, the NZE. This pathway, updated since last year to reflect changes in the past 12 months, “remains narrow but achievable”.

Specifically, global emissions increased in 2021 and are due to rise again this year. And new fossil fuel infrastructure built since last year could emit 25GtCO2, if operated until the end of its lifetime.

NEW

Global CO2 emissions will grow by less than 1% (300MtCO2) this year, according to new @IEA analysis

A much larger 1,000MtCO2 increase has been prevented by major growth of renewables & EVshttps://t.co/sqtQRf5rwR pic.twitter.com/kQAiFwMRql

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) October 19, 2022

This means the starting point for getting to net-zero is higher and the peak in emissions later, requiring a steeper decline to remain within the carbon budget for 1.5C. This extra effort to stay below 1.5C can be seen in the yellow wedges in the first chart, above.

(In line with the reduced prospects for gas in this year’s outlook, there is much less gas use throughout the 2022 NZE pathway than in the 2021 version. Conversely, the 2022 NZE has slightly more coal and oil use, albeit only in the short term.)

Bridging the gap to 1.5C would require not only higher ambition, but also a surge in clean-energy investment in what the IEA calls this “critical decade”.

The most rapid changes and the largest emissions cuts this decade need to come from an expansion of clean electricity to displace coal.

(Figure 5.10 of the report shows that across each of the IEA scenarios, around half the emissions reductions needed to 2030 come from renewables replacing coal power.)

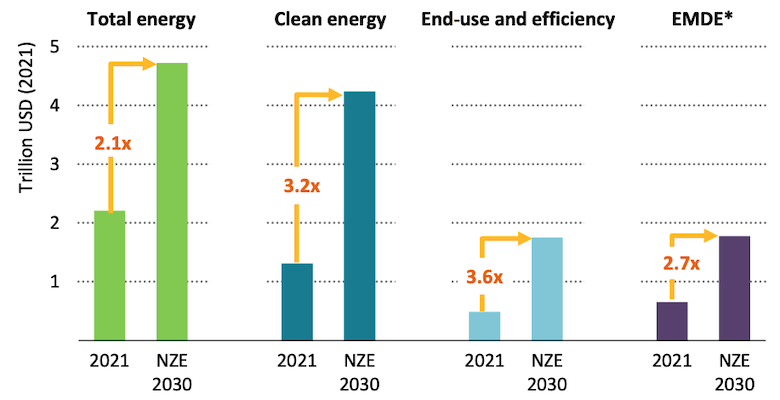

Clean-energy investment currently stands at $1.4tn per year and needs to double by 2030 to meet current climate pledges, or to triple to get onto the NZE 1.5C pathway.

Moreover, this is not simply a question of shifting investment from “dirty” to “clean” energy, the IEA says. Total energy investment needs to double by 2030, as shown in the figure below.

How current global energy investment by destination, trillions of dollars, would need to change by 2030 to be consistent with the 1.5C NZE pathway. “EMDE” is energy investment in emerging market and developing economies, excluding China. Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2022.

One key issue highlighted by the IEA is the very large gap between the cost of clean energy finance in developed versus developing and emerging market economies.

It says the difference in the cost of capital reflects “real and perceived risks” associated with investments. The cost of capital for a new solar plant in 2021 was between two and three times higher in emerging markets (at 9-13.5%) than in advanced economies or China (2.5-5.5%).

Reducing this disparity would make a “huge difference” to the overall costs of transition, it says:

“A 200 basis point [2 percentage points] reduction in the cost of capital in all emerging market and developing economies would reduce the cumulative clean energy financing costs to reach net zero emissions by $15tn through to 2050.”

Failing to lift clean energy investment in line with the NZE pathway could leave the world “energy-starved”, the report warns. This would mean an unpalatable choice between boosting fossil fuel investment to meet demand and putting 1.5C in “jeopardy”. It continues:

“If clean energy investment does not accelerate as in the NZE Scenario then higher investment in oil and gas would be needed to avoid further fuel price volatility, but this would also mean putting the 1.5C goal in jeopardy.”

New investment in oil and gas supplies would not only put climate goals at risk but would also be at commercial risk if demand fails to materialise, the IEA says. This is illustrated in the figure below for the case of liquified natural gas (LNG) infrastructure needed to transport gas by ship.

Under current policies in the STEPS pathway, demand for internationally traded gas would rise slowly (blue line). This would mean higher demand for LNG infrastructure than what is currently built (lilac area) or under construction (purple).

Some facilities being built would be surplus to demand if climate pledges are met (yellow line). And some of the existing capacity would not be needed under the 1.5C NZE pathway (green).

Existing and under-construction LNG capacity, billion cubic metres (bcm) versus demand in the three outlook scenarios (blue, yellow and green lines). Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2022.

The IEA concludes: “lasting solutions to today’s crisis lie in reducing fossil fuel demand”.

New energy-security paradigm

The global energy crisis has “stoked inflationary pressures and created a looming risk of recession”, the IEA says, as well as increasing food insecurity.

Higher fossil fuel prices mean that 75 million people who had recently gained access to electricity will lose the ability to pay for it, the outlook says. Birol calls this a “global tragedy”.

The report adds that the transition to clean energy can help reduce these risks:

“[The crisis has] underscore[d] the risks inherent in today’s energy system and the importance of energy security to our economies and daily lives. Energy transitions offer the chance to build a safer and more sustainable energy system that reduces exposure to fuel price volatility and brings down energy bills, but there is no guarantee that the journey will be a smooth one.”

The outlook says rising geopolitical tensions and the shift to clean energy call for what it describes as a “new energy security paradigm”. It sets out 10 principles for this new approach. Birol stresses that “[u]nity and solidarity need to be the hallmarks of our response to today’s crisis”.

The 10 principles are as follows:

- Synchronise scaling up of clean energy with scaling back of fossil fuels. (“Cutting investment in fossil fuels ahead of scaling up investment in clean energy pushes up prices but does not necessarily advance secure transitions.”)

- Tackle the energy demand side and boost energy efficiency. (“Since 2000, efficiency measures have reduced unit energy consumption significantly, but the pace of improvement has slowed in recent years.”)

- Reverse the slide into energy poverty. (“Turning these worsening energy poverty trends around is essential for secure, people‐centred energy transitions.”)

- Bring down the cost of capital in developing countries. (See above.)

- Manage the retirement of existing energy infrastructure. (“Some parts of the existing fossil fuel infrastructure perform functions that will remain critical for some time, even in rapid energy transitions. They include gas-fired plants for electricity security.”)

- Tackle risks for producer economies. (“Potential export earnings from hydrogen are no substitute for those from oil and gas, but low cost renewables and carbon capture, storage and utilisation (CCUS) can provide a durable source of economic advantage.”)

- Invest in electricity system flexibility. (“Reliable electricity is central to transitions as its share in final consumption rises from 20% today to 40% in the Announced Pledges Scenario (APS) in 2050 and 50% in the NZE Scenario.”)

- Diversify clean energy supply chains. (“Mineral demand for clean energy technologies is set to quadruple by 2050…High and volatile critical mineral prices and highly concentrated supply chains could delay energy transitions or make them more costly.”)

- Make energy infrastructure climate resilient. (“The growing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events presents major risks to the security of energy supplies.”)

- Direct markets but do not dismantle them. (“Governments need to take the lead in ensuring secure energy transitions by tackling market distortions – notably fossil fuel subsidies – as well as correcting for market failures. However, transitions are unlikely to be efficient if they are managed on a top-down basis alone.”)

On the final point, the IEA notes that fossil fuel subsidies have been on the rise. Box 4.4 of the report describes them as a “roadblock to a more sustainable future”. It shows that, after a large dip in 2020, fossil fuel subsidies more than doubled in 2021 to over $500bn. The IEA anticipates “another sharp increase” in the subsidy figure for 2022, thanks to high energy prices.

Teaser photo credit: Putin hosted a meeting of the Russian-led military alliance, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), in Moscow, Russia, 16 May 2022. By Kremlin.ru, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=118074423