Ed. note: This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

Data centres, precision-farming, home offices and increasing connectivity: new forms of rurality are emerging physically and conceptually, and new dynamics are at play between ‘human’, ‘extra human’ and ‘non-human’ scales. What possibilities might there be within these new inter-scale relationships? What social and environmental gains and losses are at stake?

These were some of the questions addressed by a conference in Denmark whose speakers included ARC2020’s Louise Kelleher and Matteo Metta. AlterRurality 6: Re-Scaling the Rural aimed to initiate a critical investigation of past, current, and what may become future concepts and interpretations of rural life. Report by Louise Kelleher and Matteo Metta.

Participants mingle outside the coal house. Photo: Louise Kelleher

The population of the tiny Danish coastal village of Agger was temporarily re-scaled by 20% over the space of one weekend in May, when it hosted the AlterRurality 6: Re-Scaling the Rural conference.

Organised by ARENA, in conjunction with Thisted municipality, Rural Agentur and the Aarhus School of Architecture, the interdisciplinary conference unfolded in Agger’s community centre – a sleekly renovated coal house that met every expectation of Danish design, yet stood out from the traditional seaside cottages that are characteristic of the region of Thy, a national park on Denmark’s north-west coast.

The piercing light in this part of the world lends itself to new perspectives. Over three days of working sessions, we gazed out at the fjord that glittered in the sunlight, and stepped out to inhale the North Sea air during refreshing coffee breaks. If you were quick, there was time for an even more refreshing dip in the fjord at lunch, where despite the fine weather, water temperatures lingered around 15ºC.

Over moorland to the sea: The first in a series of walk and talks in Thy National Park. Photo: Louise Kelleher

Water is everywhere you look in Thy, and as we immersed ourselves in the place, sea level rise was one of the urgent questions tackled in a packed programme. Here a 1,000-year perspective can be useful, proposed Katrina Marstrand Wiberg of the Aarhus School of Architecture, in learning from the past to understand our present and prepare for the future.

Other speakers explored new ways to visualise vast water systems. Drained wetlands, whose depleted soils are no longer useful for agricultural production, have the potential to become agents of ecological energy and co-creation. Such is the focus of research by Rikke Munck Petersen and Johanna Bendlin of the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management.

A 19th-century lighthouse built 150 m inland in preparation for coastal erosion that has not materialised at the scale predicted. Photo: Louise Kelleher

We came away from this conference with new ways to see – water and other natural resources, the countryside, its inhabitants, and its relationships with the urban. Questions of agency and extractivist paradigms were explored along with approaches to decolonising the rural.

What is the metropolitan area of Paris doing to its rural areas? asked Marie-Laure Garnier, PhD student of Laboratoire de recherche en projet de paysage at Cergy Paris University. The dumping of excavated soils from urban building sites is allowing construction firms to reshape the topography of this region. Once our eyes were opened to this practice, we became curious about every heap of earth we spotted.

In her keynote, ARC2020’s Louise Kelleher shared stories of connection, cooperation and community as the key to building rural resilience. The stories came from the Letters From The Farm series, the Nos Campagnes en Résilience project, and the new book “Rural Europe Takes Action – No more business as usual”. Photo: Matteo Metta

“Making champions of the overlooked”

Re-valuing and re-visualising were two of most striking themes over the weekend. “Reacquainting ourselves with the gods of the countryside”, as Keith Halfacree of Swansea University’s Department of Geography put it in his opening keynote. Critiquing representations of rural, and making the case for radical ruralities, Keith set the stage for intense discussions and interrogations on the shaping of rural futures.

English artist and farmer Kate Genever opened our eyes with her own perspective: “We must slow down, respect, recognise our impact, pay attention, risk, work in deep collaboration and coproduction – with all – before we even begin to consider what’s next for our countrysides”. Creativity can excel under strain, Kate explained, leading to forms of courage that makes champions of the overlooked.

Another artist who challenges representations of the rural is peasant painter Sigrid Holmwood. In her keynote she explained how she re-appropriates the figure of the peasant. Through re-enactment of the perspective of the ‘peasant that paints’, Sigrid interacts with plants, earths and pigment to decolonise her work. In Western European thinking, the peasant is pushed into a distant past despite the millions of contemporary peasants currently in conflict with modernising projects around the world.

A tractor hauls in the catch in Lildstrand, a fishing village with no harbour. Photo Louise Kelleher

Re-valuing the rural

Art is one way to re-value the rural. Can we quantify this value? Should we quantify it at all? The metrics we use to gauge rural phenomena can often be misleading. It’s a point that came up throughout the conference, and was emphasised in the closing keynote by Pieter Versteegh, a researcher and professor of architectural theory, with the Winston Churchill quote: “The only statistics you can trust are those you falsified yourself.”

The complex issue of statistics was elegantly unpacked by Sophia Meeres, a lecturer in landscape architecture at University College Dublin, with an example from Co. Wicklow, the so-called ‘Garden of Ireland’. Wicklow County Council boasts that the jurisdiction has 20% forest cover. These woodlands are the cornerstone of the council’s approach to biodiversity, as well as a treasured cultural heritage. Upon closer examination, however, it emerges that Wicklow’s “forests” are for the most part exotic commercial plantations, established since the 1980s at the cost of the natural habitat. Meanwhile trees on farmland are ignored, and thus the labour that is required to care for these trees.

The coastline around Agger has lost several villages to erosion over the past century. Photo: Louise Kelleher

The coastline around Agger has lost several villages to erosion over the past century. Photo: Louise Kelleher

Thus, assessing the contribution of the countryside to biodiversity is not as simple as counting trees. And or course, the countryside is more than nature and farming. People makes places. Cultural diversity is as necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for nature, according to UNESCO. So what happens to the intangible heritage of a small fishing village when it is developed into a generic tourist attraction? What is lost in terms of organic and dynamic interactions between people, and with the heritage site? Mathilde Kirkegaard, an Urban Designer from Aalborg University, spoke of how she explored ways to manage and safeguard cultural heritage in her PhD project, through an experiment in place-based, citizen-driven and process-oriented development of Ebeltoft fishing harbour.

Looking at the implications of digitalisation in on-farm diversification, ARC2020’s Matteo Metta shared the perspectives of farmers in a presentation entitled “Rural areas as socio-cyber-physical systems”. Photo: Louise Kelleher

In questions of rural development, we should not overlook local strategies of care and repair, pointed out Cæcilie Kildahl Kramer, a PhD scholar at Aarhus University’s Department of Anthropology. Cæcilie’s research looks at the ‘boundary work’ done by conventional farmers in the ruins of (post)-productivism: the ‘good farmer’ manages to maintain the productivity of large-scale systems by fencing off threat to the neat arrangement of the system (weeds, insects and pests).

The financial is an increasingly problematic metric for re-valuing the countryside, as the price of land and housing skyrockets in many rural areas. Yet the phenomenon of ‘zero-lease’ land in Sweden cannot be captured by monetary calculations. Qian Zhang and Anders Wästfelt, human geographers at Stockholm University, pointed out that zero-lease arrangements provide flexibility for family farms as they are forced to change – restructure, intensify or extensify – when old farming models no longer fit in the global agri-food systems.

Andreas Poulsen of Gyrup family estate and Thy Whisky Distillery, an organic dairy farm that was visited for a walk and talk. With 200 heads of cattle on 500 hectares of land, and a 10-year-old distillery, this intensive agriculture farm is an interesting case study in ambitious re-scaling, diversification and economic sustainability. The family grow heritage and modern varieties of barley, rye, spelt, which is then malted, mashed and distilled at the Estate. It’s a circular system in which the livestock play an essential role, for example by providing natural fertiliser for the grain, and consuming the mash that is leftover from whisky-making. Photo: Louise Kelleher

Re-scaling the rural from below

Indeed, it is agri-food systems that are the main concern of transition policies worldwide, noted Marine Bré-Garnier, a PhD candidate in geography. Presenting her research into the role of the ‘ordinary rural’ in the transition processes, she argued that these production basins can be both enablers and obstacles – but cannot be ignored.

If rural areas are to rise to the challenges of socio-ecological transition, however, they must have room to experiment – not least with the concept of democratic transition. The question of democratic decision-making is a hot topic in France, where Local Food Plans (projets alimentaires territoriaux, or PAT) have been imposed on rural territories in a top-down manner by regional governments.

Sabine Girard, a doctor in geography at INRAE Grenoble, related an experiment in participatory democracy in the village of Saillans, France. Over six years the citizens of the village created a “real and concrete utopia”, as they came together to collectively build a path to transition. This experience offers fascinating parallels with the local food and agriculture policy spearheaded by the village of Plessé.

Anne Mette Frandsen, with Knud Aarup Kappel (not pictured), facilitates an in situ workshop on Learning from the hyperspecific rural wilderness of Agger. Photo: Louise Kelleher

Anne Mette Frandsen, with Knud Aarup Kappel (not pictured), facilitates an in situ workshop on Learning from the hyperspecific rural wilderness of Agger. Photo: Louise Kelleher

Rural communities in Denmark are also increasingly taking their future into their own hands. But how can place-based, community-driven projects contribute to spatial and environmental justice? What role do physical interventions play in building just rural futures, and quality of life for more than humans? These questions were asked by Anne Tietjen, Associate Professor in Landscape Architecture and Planning at the University of Copenhagen, and Lea Holst Laursen, Associate Professor in Urban Design at Aalborg University, opening a debate on future directions for rural spatial development in Denmark and beyond.

Smallholdings are being re-scaled towards industrial farming, but the reverse is also true. Looking at 15 case studies of farms in Northern Italy, Luca Filippi, project manager for LIFE agriCOlture, illustrates how the success of regional food products like Parmiggiano Reggiano can also mean re-shaping the ecosystem of the Emilian Appennines, with severe climate and agri-environmental consequences. Adopting ambitious agro-environmental and forestry practices (e.g. longer crop rotations) was only possible with the joint efforts and negotiations between the local farmers, ecologists, landscape architectures, civil society organisations and policy makers.

In “Unsmart landscapes – an unpredictable countryside as our last resort”, Jens C. Pasgaard, Tom Nielsen & Morten Daugaard argued that smart can mean the same as a (digital) growth path. As the digitalised countryside becomes predominantly organised by rational, instrumental, and functionalist principles, we need to unpack the good intentions behind single smart strategies and unveil their requirements and consequences for rural areas in the context of urgent climate change actions (e.g. new facilities for green electricity production, new e-commerce territories, progressively streamlined agricultural production, highly optimised landscapes).

Learning from the hyperspecific rural wilderness of Agger: Karin Dubsky adds seagrass, a key species for climate change adaptation, to an in situ creation co-curated from objects found by the participants of the conference. And yes, the wheelie bin is a found object! Photo: Louise Kelleher

“Kidnap an ecologist”

What made this conference so powerful was the unique mix of interdisciplinary knowledge and experience that swirled around the space. Above is just a flavour of the smorgasbord of presentations we heard that were informed by architecture, anthropology, sociology, geography, art, farming and more.

Karin Dubsky, farmer, ecologist and founder of Coastwatch, brought home the value of this interdisciplinary approach in a keynote address entitled “Our shared future”. Education, awareness and citizen science are at the heart of Coastwatch’s work, which empowers and encourages everyone to become a custodian of our coastlines. In the face of the biodiversity collapse, Karin urged every academic department to “kidnap an ecologist” to ensure that biodiversity considerations are at the heart of any development.

This comes back to the overriding question of agency that permeated the weekend. Why do we ‘develop’ rural areas – and for who? Similarly, when we speak of a green transition – who is being transitioned, and why? In ARC2020’s work to support socio-ecological transition, this Danish conference was a reminder to make democracy and participation a starting point: to listen to rural voices, to observe the human and non-human, to see rural realities, whether radical or more ordinary.

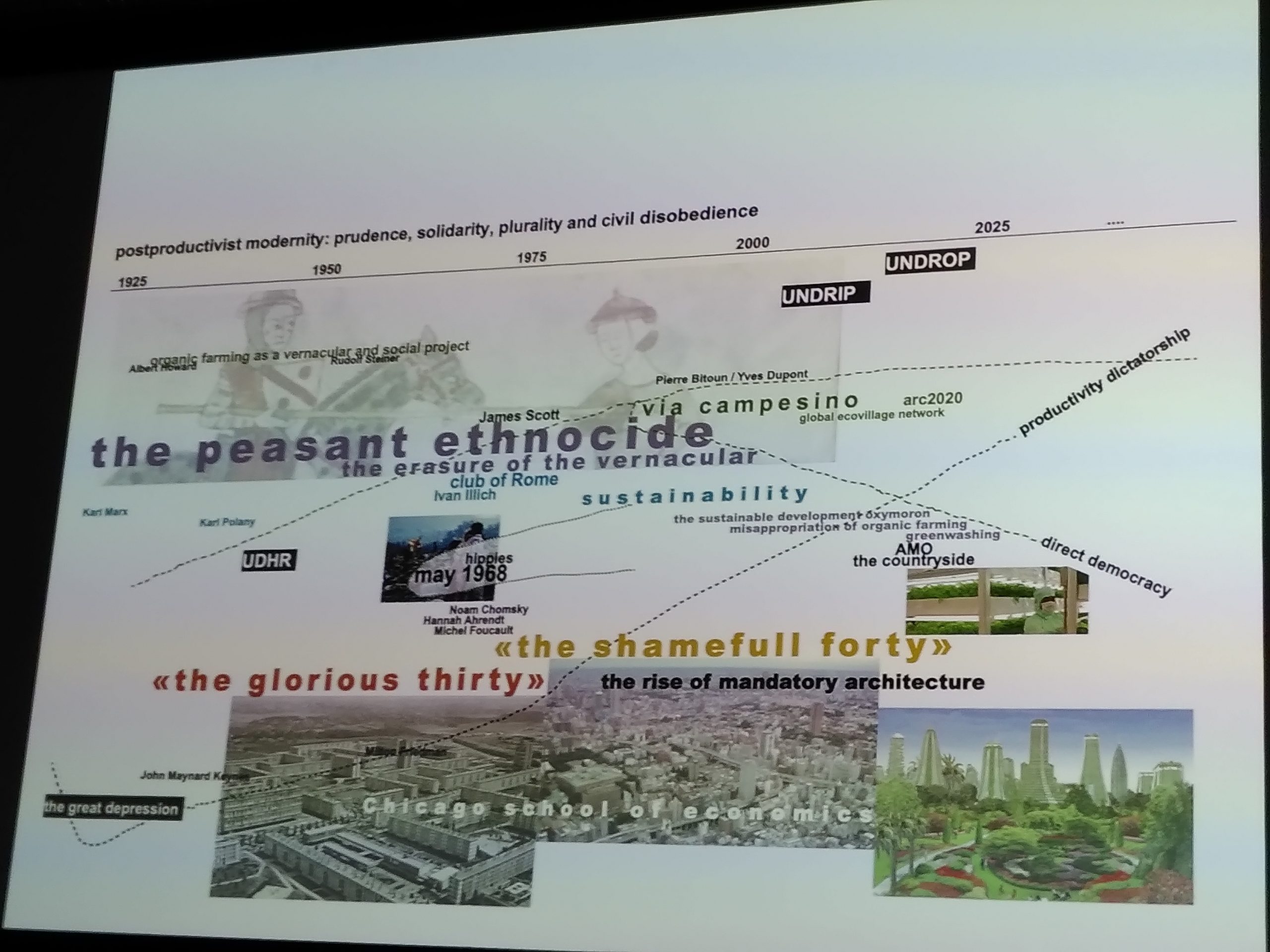

Pieter Versteegh, in his closing keynote, featured ARC2020 in a timeline of prudence, solidarity, plurality and civil disobedience in the era of post-productivist modernity. Pieter mapped the fall of direct democracy against the rise of productivity, as a result of corporate colonialism in the ‘great genocide era’. Photo: Louise Kelleher

In his final keynote, Prof. Pieter Versteegh reminded us of the historical path of rural development across the globe, signed by centuries of European colonialism, then urban colonialism, green revolutions and many other forms of powers in re-scaling or de-scaling rurality. It isn’t easy to deal with new development dilemmas such as smart villages, precision farming, and re-wilding.

Concepts and talk about hyper-productivism, smartification, or greenwashing lose their power to change the current system when confronted with the nuances of everyday reality, which is established upon a network of privileges, inequalities, and dependencies in which we all are trapped – to different extents. At the same time, the loss of democracy or biodiversity collapse cannot wait too long for our actions.

Therefore, in addressing contemporary dilemmas, we must understand that academia, rural sociologists, architects, policymakers – and anyone who enjoys the privilege of speaking on behalf of ‘others’ – should make every effort to involve those who really struggle on the ground: the artists, the small-scale farmers, the young students, and the minorities who live precariously in rural territories. It is only by overcoming their barriers and supporting their engagement that we can break with closed-circle discussions and become agents of social change in re-scaling the rural.

Click here to view Louise Kelleher’s keynote presentation, “How To Build Rural Resilience: Stories of connection, cooperation and community”. You can read these on-the-ground stories of resilience, and more, in the Letters From The Farm series, the Nos Campagnes en Résilience project, and the new book “Rural Europe Takes Action – No more business as usual”.

Learn more about Matteo Metta’s work on Rural Perspectives on Digital Agriculture and CAP Strategic Plans.