My husband has attention deficit disorder. Well, he hasn’t actually been diagnosed. He’s way too ADD for that. Trying to get Erik a diagnosis in the Netherlands, where we live, involved multiple phone calls to get referred to the right place; form-filling and questionnaires; a long wait to get an appointment; having to go over the forms and questionnaires with an assistant psychologist; digging out old school reports; and arranging interviews with Erik’s dad (who has suspected ADD) and brother (who has diagnosed ADHD) to find out what he was like as a child.

Needless to say, Erik did not complete the process. It’s a miracle that anyone with the neurological condition does. ADDitude mag, a publication for people with ADD and ADHD, lists the signs of ADD as: “poor working memory, inattention, distractibility, and poor executive function”. Executive functions are skills that help you get things done like plan, manage time and multitask. Erik doesn’t have the ‘H’ in ADHD – he isn’t that hyperactive. But people with ADD don’t get on with bureaucracy.

Erik doesn’t appreciate being told that the way his brain works is “poor”. He spent the first 40 years of his life not knowing that he might have ADD. Instead, since childhood, he was told that he was weird, stupid or broken. He then spent five years wrestling with the idea of having it: first rejecting the label, then accepting it in private but still feeling afraid to talk about it to others.

“My whole life people have thought I’m a clown. I don’t want to give them confirmation,” is what he said when I asked why he never mentioned it to friends.

The reason people think he’s a clown is that he’s the most creative thinker I have ever met. Erik is a visionary. He has big ideas, big dreams, big plans. He’s not always so hot at carrying them out. Unfinished projects include our first flat that we lived in half-built for eight years; a new internet protocol; and a new intellectual property regime for pharmaceuticals.

Now, at the age of 45, Erik is adopting what he calls the ‘LA mindset’: owning his divergence. It’s a journey we’ve been on together, him with his ADD and me with both a chronic autoimmune disease I was diagnosed with in 2017 and facing up to the fact that the binge drinking and chain smoking of my youth may have been about something deeper than me doing my British patriotic duty.

The books of the Hungarian-Canadian medical doctor and writer Gabor Maté have guided us on our journeys. Maté has written about ADD (he has it), chronic illness, and addiction and compulsive behavior (he exhibits it).

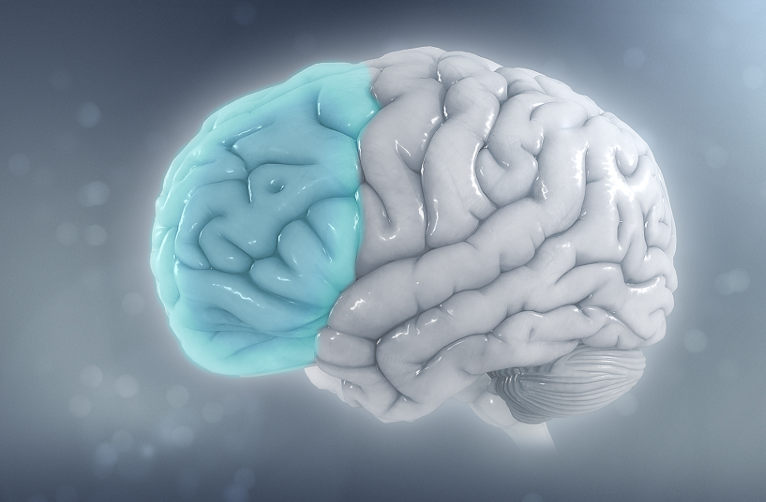

Maté dissents from the mainstream consensus on what causes ADD, which is that it’s mostly genetic. He says that while there is a genetic element, what determines whether or not you develop it is the extent to which you receive the right nurturing in infancy. Five-sixths of human brain circuitry is wired after birth. Those with ADD have different wiring in the prefrontal cortex, which controls self-regulation and attention. For optimal brain development to occur, infants need food, shelter, and secure attachment with their primary caregivers.

You can’t blame the parents, though. Not receiving the right nurturing doesn’t necessarily mean abuse or neglect, though it can. Parents being stressed out and not being able to attune to their infant can do the job. Maté was born to Jewish parents in Budapest two months before the Nazis occupied the city. But it doesn’t have to be that extreme. Show me one parent who isn’t stressed to the eyeballs struggling with work, finances and trying to raise kids without enough help and on no sleep.

These are individual neurophysiological features but they arise within social contexts. Our capitalist societies create stressed-out families, carceral schools and toxic workplaces. No wonder our brains are going haywire on an unprecedented scale. ADD is a capitalist condition.

ADD is the new schizophrenia

I’m not the first person to say this. In his 2011 book ‘Capitalist Realism’, the late Mark Fisher wrote that ADHD was “a pathology of late capitalism – a consequence of being wired into the entertainment control circuits of hypermediated consumer culture”.

Gabor Maté is clear that ADD is not a pathology; it is a developmental divergence. It isn’t fundamentally caused by our era’s hypermediated culture, he argues – however, culture can and does feed and reinforce it.

Fisher was riffing on critical theorist Fredrick Jameson’s metaphor of ‘the schizophrenic’ as typical of 1980s postmodern culture. Jameson described a culture in which we are constantly being bombarded by random images, a ‘series of pure and unrelated presents in time’. He wrote that people with schizophrenia embodied the fragmentation of identity that this experience of time creates: the failure to craft a coherent sense of self that connects the past, present and future.

Other thinkers of the late 20th century had their own unorthodox theories of schizophrenia, notably philosopher Gilles Deleuze and psychoanalyst Felix Guattari in their 1972 book ‘Anti Oedipus’.

Fisher, a further-education teacher cum philosopher, pointed out that the culture industry had moved on since Jameson was writing in the 1980s. Fisher wrote: “What we in the classroom are now facing is a generation born into that ahistorical, antimnemonic blip culture – a generation, that is to say, for whom time has always come ready-cut into digital micro-slices.”

For Fisher, the person with ADD, with their distracted focus and ‘poor working memory’, was the updated symbol of our age. And that was 2011, well before TikTok and Instagram Reels.

What Fisher didn’t mention was that for Deleuze and Guattari, if not for Jameson, schizophrenia was not just the condition of late capitalism, it was also its exterminating angel. By giving rise to postmodern schizophrenia, they argued, late capitalist culture was sowing the seeds of its own demise. Late capitalism (AKA neoliberal capitalism) is disorderly, chaotic, unruly. It’s the economic Wild West, where money is king, finance is fictitious, and all barriers to its flows are bulldozed. This creates cultures and subjectivities that are also disorderly, chaotic and unruly.

But at the end of the day, capitalism needs order, stability and rules. It needs the state. It needs the state’s militaries, its laws and its bureaucracies. And it needs good, stable, reliable citizens to do its bidding. The chaos and disorder of schizophrenia threatens to disrupt the whole system.

To be honest, I’m not sure if using a serious mental illness as a metaphor for our modern malaise is OK. For theorists like Deleuze, though, it was important to see mental illnesses as political rather than natural and private categories. They are experienced by individuals but they are produced in and by societies. The personal is political.

The same can be said for neurological differences like ADD. And, like schizophrenia, ADD can similarly be understood not only as our era’s totemic condition but also as its Trojan Horse.

ADD against the clock

“ADHD is at its heart a blindness to time,” says pre-eminent ADD expert Russell Barkley. Erik disagrees. It’s not a blindness to time, he argues, but an oblivion to a particular social construction of time: regimented clock time.

Capitalism instituted an economy based on wage labour and with it, the commodification of time. Time became money. Or more precisely, workers’ labour time became capitalists’ profit.

In ‘Hours against the clock: on the politics of laziness’, Lola Olufemi explains how capitalism captures time, turning it into a finite resource that we are forever losing to our work. Productivity growth, the mantra of capitalism, means speeding up production so that we are always producing more in the same amount of time.

We see the tyranny of capitalist time most starkly in Amazon warehouses where workers’ every movement is monitored by algorithms and the least productive regularly fired. We see it in poultry farms where workers are forced into wearing diapers because they don’t have time for bathroom breaks.

Due to differences in wiring and chemistry in the brain’s frontal lobe, the person with ADD does not experience this kind of linear time. Gabor Maté says that, for ADDers, there are two states of time: the here-and-now and the ever after. I am constantly reminding Erik that time passes. If I tell him it’s 2pm, he will continue to believe that it’s 2pm until I tell him that two hours have passed and it’s now 4pm. Similarly, he has no concept of not being on time for a meeting until the appointed time has already passed and he hasn’t left the house yet.

You can see why this kind of human is inimical to an economic system grounded in the regimentation of time. Good luck trying to get a person with ADD to get to school or work on time, do set tasks for certain durations and then go home and do whatever they need to do to be able to do the exact same thing tomorrow.

Because we are always on the clock, even when we’re free. In the evenings we are preparing for work tomorrow. On the weekends we’re trying to forget about work while making sure our sleep routine doesn’t get so messed up that we can’t get up on time on Monday. On holidays if we’re lucky we get to unwind for a few moments before having to start back again.

Not to be flippant, but I’ve always thought of the alarm clock as a violation of human rights. For people with ADD, it literally is. They are notoriously poor sleepers. But like many things about them, their sleep is only ‘poor’ because of the time pressures exerted upon them by school or work. Erik’s intrinsic sleep pattern seems to be biphasic. He has one phase of sleep at night and then another in the morning or after lunch. This would be completely fine if his current job didn’t require him to be in from 9 to 5. In fact, the latest sleep research suggests that human sleep is naturally biphasic. It’s capitalism that demands – and then makes sure you fail to get – the solid eight hours.

Erik is high functioning. When we met he was a risk analyst at a major bank. But he can only take the tyranny of time for so long. Eventually, usually after a year or two, he will quit and need to reclaim his time, and his sleep. We are privileged to be able to afford to live like this, though it isn’t always easy. Millions of ADDers, along with billions of non-ADDers, never escape the grind. But who knows, if we collectively adopted the ADD non-compliance with capitalist time, maybe we could.

Capitalist bureaucracy

You may associate bureaucracy with a bloated state, but the term ‘Kafkaesque’ is more apt under today’s hyper-capitalism than it has ever been. Have you ever tried reaching Airbnb customer service? The late David Graeber argued that the notion of bureaucracy as just a problem of a large state is propaganda. For him, governments and companies are barely distinguishable from each other in their bureaucratic hellishness.

State and private sector bureaucracies are in fact often intertwined. In the Netherlands, if you are behind on some tax or other, government departments hire private debt collectors to come after you. Once in their grip, it’s almost impossible to extricate yourself from ever-mounting fines and fees. The trauma that Erik has suffered from harassment by these bailiffs is no joke. (One of his projects is to set up a ‘national union of non-payers’, but he hasn’t quite gotten around to it yet.)

If there’s one thing the ADD brain can’t handle, it’s bureaucracy. Due partly to reduced dopamine levels, those with ADD find it virtually impossible to devote any amount of time to activities for which they have no internal motivation. If you want to get an ADD kid to do their maths homework, you need to structure it like a video game that delivers a hit of dopamine every time they score a point.

Let’s face it, along with straight-up bureaucracy – which takes up an inordinate amount of our time and for which are paid nothing – much of the paid work we do can also pretty much be classified as bureaucracy. It has no intrinsic meaning, it adds no value to society and we do it purely to get money to stay alive. Again, those with ADD are unable to motivate themselves to do things that have no intrinsic meaning. We can ask ourselves why any of us can – when you think about it, who is it really that has the disorder?

ADD is an anarchist

This is not to say that people with ADD are lazy. Far from it. Erik is pretty much a workaholic. Like many people with ADD, he has hyper-focus for certain things. For him, it’s making movies and 3D graphics, sewing, learning about cryptocurrency, playing the guitar and gardening. Just not for things that other people tell him to do.

If anything, Erik embodies Karl Marx’s ideal communist human. Marx wrote that, under capitalism’s regime of labour time, “each man [sic] has a particular, exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape. He is a hunter, a fisherman, a herdsman, or a critic, and must remain so if he does not want to lose his means of livelihood”.

But under communism, with democratic control over production, we would be free to develop our talents at will. It would be possible “for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic”.

The ADD brain is not made for pointless drudgery. It’s made for creative, free-form thinking, where connections fire off in all directions. The same wiring that generates internal chaos and distractibility also means that ADDers are better at ‘divergent thinking’, ‘conceptual expansion’ and ‘overcoming knowledge constraints’.

True, capitalism often ends up befitting from the ADD non-engagement with bureaucracy, as those bailiffs will attest. The individual with ADD will most often be the one getting harmed. Or, let’s be honest, the ADD person’s long-suffering partner will end up doing their bureaucracy for them, especially if that partner happens to be of the female persuasion.

But still, the ADD brain’s point-blank refusal of capitalism’s hijacking of time through both wage labour and bureaucracy, and its insistence on creativity, pleasure and self-expression, should be seen as a source of raw, joyous, anarchic rebellion.

Love is a doing word

For Gabor Maté, while medication may be helpful in many cases, it should never be the first or only port of call for treating ADD. ADD is not a disease. It’s a neurodevelopmental difference, caused by families that are too stressed-out by the pressures of life to give their kids the attention they need.

People with ADD have been brutalised by society. The same goes for addicts and for people with chronic diseases. The good news is that people can heal at all stages in life. What they need to be able to do so are spaces where they are accepted and given room to pursue their passions, connect to their feelings and nurture their self esteem. In other words, what they need is what everyone needs.

I’ve always said that love is not just a feeling, but a verb, an action. Apparently I’m not the only one to think this. The American psychiatrist Scott Peck defines love as action, as the “willingness to extend oneself in order to nurture another person’s spiritual and psychological growth, or one’s own”. Maté ends his book with the words:

“If we can actively love, there will be no attention deficit and no disorder.”

We owe it to each other to create those spaces of active love and healing. Along the way, we can all learn from the ADD brain’s refusal of labour time and capitalist bureaucracy. We can all adopt its defiantly creative, lateral thinking. We can all embrace the disorder that will set us free.

Teaser photo credit: The left prefrontal cortex, shown here in blue, is often affected in ADHD. By https://www.scientificanimations.com/ – http://www.scientificanimations.com/wiki-images/, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71960037