The COVID-19 pandemic saw an influx in the number of mutual aid groups popping up across the country. Now, as the world trepidatiously welcomes a “new normal”, communities are reassessing their needs and capacities. Many newly-laid networks of mutual aid have been forced to adapt, reassess, and reimagine their role in protecting and providing for the communities.

Such is the case in Chicago. During the pandemic, approximately 40 mutual aid groups sprang forward to address the growing numbers of citizens who were or were becoming food insecure. Market Box was one of them.

“We wanted to make sure there was an alternative for folks who needed to access food and for them to do so without risking their lives or catching COVID 19,” said Hannah Nyhart, Market Box co-founder. In addition to her work with Market Box, she’s also co-owner of Build Coffee, a café and bookstore located in Experimental Station. The Woodlawn-based Station acts as a community hub and business incubator where people from various organizations democratically coalesce to “build independent cultural infrastructure” on Chicago’s south side.

When Market Box began, Nyhart and other Market Box co–founders from Invisible Institute and South Side Weekly were all tenants at Experimental Station. During the pandemic, they became inspired to help people who they saw had difficulty accessing food or were unable to receive food deliveries safely.

“Back when COVID first hit, I had a friend whose mother was receiving Market Box,” said Zakiya McKinley, a real estate agent, Market Box recipient, and volunteer who rallied her mother, daughter, aunt, and sister to help deliver food to neighbors in need. “[This friend] reached out to me knowing that I am the mother of a child on the autism spectrum. She thought Market Box would be a help, and it was,” McKinley said. She shares the food she receives in monthly events she calls ‘mini-Christmases’ where she cooks a meal for about six neighbors—three of whom are elderly.

The pandemic pushed many communities into food insecurity, including elderly and immunocompromised individuals, families of those who’d recently lost employment, and those left without access to transportation or governmental support.

But Market Box says they were aware of the pre-pandemic issue of food insecurity in Chicago’s food deserts. These deserts existed prior to the pandemic and continued to prevail in Black and Brown communities where, according to an Illinois Institute of Technology study published in July 2021, 26 of 57 communities with below-average access to food were African-American neighborhoods.

Compounding the effects of pre-existing inaccessibility, the pandemic made it harder for these communities to find aid, access or resources.

“The other need that we saw is that all of the farmer’s markets were shutting down [due to safety mandates], so suddenly there were no clear channels for folks to go and access fresh food,” Nyhart explained. “So we had people who were shut off from their usual outlets for getting food. We had people who wanted to help but didn’t know how or who had produce and not the usual channels for selling it.”

Market Box was born out of these three needs, designed as a way to crowdsource funds to purchase foods from farmers and then deliver it to people’s homes. Their distribution network covers families living south of Roosevelt Road and north of 95th Street and from Lake Michigan on the east to Western Avenue on the west.

“Within these boundaries, we deliver to primarily Black and Brown folks who have identified themselves as needing assistance. We do not ask for verification of the need. Market Box goes where called within those boundaries. We are built for and by the south side of Chicago,” Nyhart said.

Reverend David Black of the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago agrees. He feels that, while Market Box’s efforts at direct aid serve as an immense contribution to the community, the effect of their work is even deeper than it appears on the surface.

[Market Box’s work] reinforces a culture of expectation that we can, we must, and we will take care of one another, especially in the middle of a global disaster when it feels like the world is ending. — Reverend David Black

With the help of 288 volunteers, Market Box orchestrates bi-monthly food deliveries to over 509 households reaching over 1200 people. Even as the pandemic declined and pantries, restaurants, and other food services returned to normal operations, Market Box retained 80% of its list and added 102 households over the last 12 months.

“Over the next few months, we will be increasing our household deliveries by 40 households,” Nyhart added.

While Market Box may be a recent addition to the South Side’s network of solidarity, the practice of mutual aid is not new to the area or its people. In fact, mutual aid has deep roots in Black, Indigenous, and immigrant communities.

In the 1800s, free African American communities pooled their resources to care for the elderly, widows, and children or to buy land. Mutualista societies, located in Texas in 1922, collaborated to help Mexican immigrants learn English and garner resources, like food and housing. In 1969, the Black Panthers sponsored free breakfast programs in Oakland and San Francisco, California.

Unlike pantries or charities, mutual aid organizations are defined by reciprocity. “People support each other by based on what others need and what they can provide, unlike charity and government assistance, which are one-sided giving,” writes Margaret McAden in the article Mutually Inclusive.

Mutual aid organizations can also differ from pantries in that they may not have set or permanent locations from which they work from, distribute or source food. According to 19th Ward Mutual Aid organizer and founder Tim Noonan, most pantries get their food from food banks, donations, or drives whereas quite a few Chicago-based groups utilized USDA’s Farmers to Families Food Box Program, before it was discontinued in May of 2021.

Market Box used a different model for operating. In 2021, Market Box raised $200,000 from individual donors and small organizations. That money was used to purchase food from small to medium farms with 90% of the food being sourced from the Midwest. The following summer, 80% of Market Boxes’ source farms were within a one state radius.

Run democratically by volunteers who organize food, coordinate deliveries and track the recipients, Market Box distributions are parceled by trust.

We trust that people know what they need, and that people are going to show up for one another. We don’t need any type of identification or verification. Working on that trust has meant that we are able to use the networks that already exist.

Nyhart believes this network of trust strengthens Market Box’s work and their ties to the community. “Some recipients may ask for an extra bag for a neighbor who needs food, too. That makes it easier for us to reach folks who need the help,” she said.

Nyhart credits Market Boxes’ hardiness to the continued commitment of their volunteers and the input and feedback of their recipients. “It’s been such a huge learning curve for all of us, but one thing that I’ve been really proud of is that we have sustained relationships with people for two years. We are more regular than the post office. We’ve been able to show up from month to month, and part of that is that we have this really committed volunteer base,” she said. “The heart of Market Box is the people.”

Like other mutual aid groups, Market Box has had to make some adjustments due to learning curves, too.

Nyhart says that when they first started packaging and delivering boxes, the team underestimated the amount of manpower needed for such an operation to run smoothly. One of their first efforts took place back in January 2021. At the time, they were still worried about the potential spread of COVID indoors, so they packed boxes outside. The cold weather was particularly unforgiving and before they had time to finish their work, drivers began arriving expecting to load and deliver food to waiting families.

“But it ended up being really beautiful,” Nyhart said. “Because what happened was that all these people who had signed up to come deliver bags spent the first half hour packing with us. It was very messy, but it also meant that everybody got to meet each other. Everyone [was] in the trenches together. Looking back, I feel really good about how things turned out even though I would have done it differently. But we learned.”

The group has had other watershed moments that led to growth or new arrangements. In the coming years, they plan to identify, integrate, and purchase more food from Black and Brown farmers. They currently source from small midwestern farms owned primarily by white families. They have transformed from a coalition into an independent 501(c)(3) organization, which they hope will bolster their fundraising. Recently, the group also moved operations from Experimental Station to First Presbyterian Church.

“We are thinking about how to really make this space our home over the next few years and how to really engage the direct community and spot some grant funding that will allow us to increase our distribution by 10%,” Nyhart said. “The biggest thing is that we’re thinking about how to continue shaping what was started as an emergency response into something that can sustain year after year.”

This article originally appeared on Shareable.net.

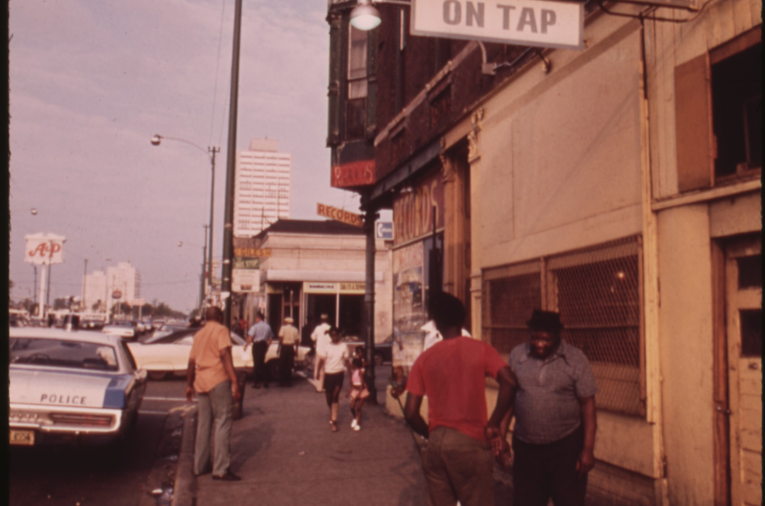

Teaser photo credit: By John H. White, 1945-, Photographer (NARA record: 4002141) – U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16914318