The origins of the free and open-source software (FOSS) movement in the 1980s are typical of a social movement. It was triggered by the frustration generated by the expansion of intellectual property rights (IPR) to software, perceived by many software developers and researchers as a barrier to their ways of working, their values, freedoms and productivity. However, only in the 1990s, with the advent of the world wide web, could the movement really take off. This happened when dispersed developers, driven by varying motivations – initially not mainly economic – began to come together, forming new types of communities, based on collaboration, voluntary contributions and original forms of governance.

From the beginning, however, the main innovation introduced by FOSS was to turn around property rights. FOSS licences work under a regime of what Yochai Benkler termed ‘open access commons’, which makes this kind of commons different from the characterisations, dilemmas and principles of governance that Elinor Ostrom developed in her Nobel Prize-winning studies. This has many important implications, both in the modalities of governance and in the forms of generation and appropriation of value. The most relevant is that this regime denies the ‘right to exclude’ or the exclusive rights of the owner. With that, it removes the possibility of selling the property or selling the right to access and use the resource, and in this way to appropriate its value, at least privately and exclusively.

In this article I try to understand the significance and evolution of free and open-source software in the wider context of the transition now underway in the organisation of production shaped by the new revolution in information and communication technology (ICT). It is only from this perspective that we can understand both the true significance of FOSS and its surprising evolution in relation to the capitalist ICT markets and the novel character of the current transition.

From the margins to the mainstream

Software production is the core of the digital revolution. The surprising development I want to highlight and analyse is that FOSS, a phenomenon born on the margins of industry and organised around a commons on the frontiers of software innovation, has become the standard model for software production.

Three recent developments indicate that something interesting is going on. First, in 2018, Microsoft, formerly the fiercest ‘enemy’ of FOSS (depicting the free software as a ‘cancer’, undermining the software markets) announced the acquisition of GitHub, the main platform for FOSS development. The news shocked many, but the move was the culmination of some radical repositioning by Microsoft, which had begun years earlier. Shortly after this, IBM – in a game of catch-up with Microsoft – bought Red Hat, the biggest open-source services company, for $34 billion. Finally, the European Commission imposed a spectacular €4.34 billion fine on Google for abusing its dominant position in mobile telephone technology, which it obtained through its open-source Android operating system. Together, these three occurrences give us an idea about far-reaching changes in the relation of FOSS to the capitalist market, challenging us to rethink our interpretations of FOSS as a digital commons.

To understand both the significance of FOSS and its evolution in the context of the current transition in systems of production, we need to understand the relations these changes entail between technology, the economy and institutional forms, including forms of ownership and governance. Such an understanding can best be approached through the framework of a techno-economic paradigm (TEP).

This idea, proposed by Carlota Perez, involves the notion of ‘a technological revolution’ in capitalist production, which she defines as ‘a set of inter-related radical breakthroughs, forming a major constellation of interdependent technologies’. The emphasis is on the strong interconnection and interdependence of the systems that make up this paradigm, in both their technological and their economic aspects. This approach also stresses the power of these breakthroughs to profoundly and simultaneously transform the entire economy and society as a whole, including the state. Currently, on Perez’s analysis, we are moving from a faltering paradigm of mass production (sometimes referred to as ‘Fordism’) to a new paradigm centred on information and communication technology.

An emerging system of production

The notion of a techno-economic paradigm captures the set of highly interconnected technical and organisational innovations that define a new ‘common sense’ regarding the best model for efficient production that will guide the dissemination process across all sectors and provide the patterns for framing both problems and solutions. A new TEP emerges and develops in two distinct phases: the installation period and the deployment period.

According to Perez, these transitions begin when a previous paradigm has exhausted its potential for growth in productivity. The first phase of these technological revolutions is typically led by financial capital, speculative bubbles and a laissez-faire ideology, and aims to override the power of old production structures, to finance new entrepreneurs and to allow a period of extensive experimentation. This phase typically ends with a financial collapse.

It is by coming out of the ensuing depression that periods of great prosperity have been unleashed, by exploiting the enormous potential for transformation that has emerged embryonically in the first period. Whether these possibilities are fully realised depends on whether the powerful industries and organisations of the previous paradigm, including their associated state and civic organisations, use the new technologies to reinforce their entrenched positions and institutional power structures – for example, corporate use of new technology to control labour and reinforce forms of exploitation typical of mass production (or mass delivery); or whether the new forces can reshape the institutions, spread the gains from the new technologies more widely and more sustainably, and reach a new social and environmental settlement.

Historically, these readjustments have only taken place under radical political pressure to reverse the dislocations produced by the previous period of rampant market domination. This is also true because they have entailed a major overhaul of the institutional order. Each paradigm shift has in fact required institutional and cultural discontinuities so deep that one can speak of a succession of ‘different modes of growth in the history of capitalism’.

This concept of a TEP enables us to understand FOSS as more than a radical but marginal innovation that has been incorporated and normalised but rather as a vital element of the current transition in forms of production. An understanding of FOSS therefore helps us understand the character of this transition and the research that needs to be done to understand the different paths it and the ecosystem of which, as we shall see, FOSS has become a part, could take.

The widespread absorption of FOSS into the capitalist market, in fact, requires a review, or at least a reworking, in particular of the early framing of the relations (summarised at the beginning of this article) between the capitalist market and the digital commons. To this end, I offer three concepts in order to organise a new approach to these relationships: semi-commons, shared infrastructure and ecosystems creation.

Semi-commons

The concept of ‘semi-commons’ describes the basis on which markets and the commons co-exist and eventually grow in parallel. One example would be the medieval lands that accommodated two kinds of activities – farming and grazing – carried out at different times of the year, as well as two different regimes of property – commons and private.

Applied to the analysis of modern communication networks, it points to a two-tiered framework based on the co-existence of a double regime of property and economic activity in the same system of resources. This framework can house the variety of ‘open business’ models emerging around FOSS: sale of services, support, certifications, the development of ‘freemium’ offers and the integration of property-based additional software features. The software remains a commons that cannot be appropriated in an exclusive way, but on top of this shared base, different forms of commercialisation and markets can be devised or generated.

Shared infrastructures

This two-tiered semi-commons sustains the rationale that is most used for explaining companies’ adoption of FOSS: ‘shared infrastructures’. In such cases, market actors are mainly users or buyers of software, rather than producers and vendors of software and related products or services. For these actors, FOSS, as a commons, provides a way to share and economise on the costs and risks related to the access to and use of necessary components of production.

Although these forms of collaborative ‘decommodification’ are far from easy to achieve, the sharing of resources is made easier by leveraging certain characteristics of the digital commons, such as its non-rivalry in use or its practically non-existent marginal costs. The dominance that Linux achieved in servers or cloud computing are examples of this use of FOSS to build shared infrastructure. At the same time, the extremely concentrated structure of the cloud computing market shows, once again, how FOSS can go hand in hand with new forms of market concentration.

The generation of ecosystems

If semi-commons explains the basic logic, and a shared infrastructure is the most widespread rationale for the adoption of FOSS by market players, the third concept – ‘the generation of ecosystems’ – highlights how FOSS, as a commons, has been used to implement innovative capitalist competition strategies. Google’s Android represents the clearest and most successful example.

This strategy is based on a multi-layered modulation of ownership regimes and consists of disrupting a market by ‘decommodifying’ a crucial layer of an industrial ecosystem – in the case of Android, the operating system used by the mobile phone industry. In this case, the objective is to shift competition in an industry into a more advantageous terrain; to attract users, developers and various types of business ecosystems to a new standard, infrastructure or platform; and to exploit the growth or creation of complementary markets, which are adjacent to and correlated with the FOSS commons.

As the recent fine imposed on Google by the EU Commission shows, these cross-subsidy practices can be used as a kind of innovative dumping strategy, which aims to eliminate competitors, trigger adoption and various types of network effects, and achieve monopolistic positions. ‘Surveillance Capitalism’ analysed and exposed by Shoshana Zuboff, which revolves around the hoarding and exploitation of user data, has been a fertile ground for these strategies. But these modalities of competition are increasingly expanding beyond software itself.

Hybrid forms of ownership

Several ideas can be gleaned from this framework to guide future work on these new commons. First is the need to study these new commons, born on the frontier of the digital revolution, as hybrid configurations that combine different regimes of ownership and economic exploitation, rather than as ‘pure’, isolated and autonomous systems. This nested structure, in fact, seems omnipresent and is also applicable in the purest community-centred projects. But most importantly, it is crucial to take it into account in order to understand the economics and politics of these new multi-layered productive ecosystems.

Second, despite their idiosyncratic structures, markets and commons can not only co-exist, but can expand in parallel or in synergy. Third, however counter-intuitive it may seem, there can be forms of capitalistic competition that are based on the creation of the commons. And fourth, the emergence of these new commons and their different configurations with the markets allow us to spot several potential areas for new kinds of public policies: from anti-trust to the modulation of a new kind of mixed political economy.

Reappraising the relationships between the commons and markets

The development of the digital commons, with its denial of the exclusive rights of the owner to appropriate its value privately and exclusively, was seen as either exciting or frightening, depending on one’s perspective. Initially, FOSS was celebrated by many for its anarchic features. And still today, FOSS is sometimes considered as a sign of an emerging post-capitalist mode of production. Conversely, it was relatively easy for Microsoft to leverage instinctive fears in the business world, where it was perceived as a threat to their markets and profits. Indeed, I would argue that, to some extent, the participation of companies in the development of FOSS means that they are contributing to processes of ‘de-propertisation’ and decommodification.

From another perspective however, it could legitimately be argued that by producing freely shared goods, these companies are engaging with and contributing to the expansion of a modality of value creation and appropriation that is distinct from the market. It is clear that, despite its idiosyncratic form with respect to its commercialisation as a product, the surprising success of FOSS would not have taken place without the increasing engagement of companies in its use and development. This was a goal deliberately pursued by the business-friendly branch of FOSS, which divided the free software movement in the late 1990s and can now justifiably celebrate its achievement.

FOSS and the new techno-economic paradigm

Thus, returning to my focus on the importance of FOSS for the current wider changes in technological and economic relations and forms of organisation, we have seen FOSS move from the margins and challenge the dominant market/state dichotomy. By growing forcefully throughout the installation period, it is on course to become the essence of the information systems and infrastructures that will permeate the new TEP. The FOSS ecosystem has successfully installed a new institution, what has been called ‘a contractually reconstructed commons’. The spectacular growth of FOSS therefore indicates that new kinds of commons could potentially play a central role in the new paradigm. Conversely, the missed engagement with these new commons (for example, by public institutions) could represent one of the blind spots generated by what Perez understands as the present ‘impasse’ in the unresolved transition from the installation phase to the deployment phase of the new paradigm. A more serious engagement with these novelties could help to clarify different possible directions in the search for a new conceptual and regulatory framework adapted to its potential. However, the necessary clarification of these dilemmas can only be made through politics.

There are many reasons to think that one of the most crucial areas of innovation in the near future could come from public policy. So far, the public sector has lagged behind the market in dealing with these novelties, and it remains to be understood how it can productively engage with, participate in and contribute to the further development of the FOSS ecosystem and production model. It is significant that the Chinese government has already made a commitment at the highest level to answer the question. It is a vital issue to be addressed by all those with an interest in democratic, non-exclusive, commons-based economic relations.

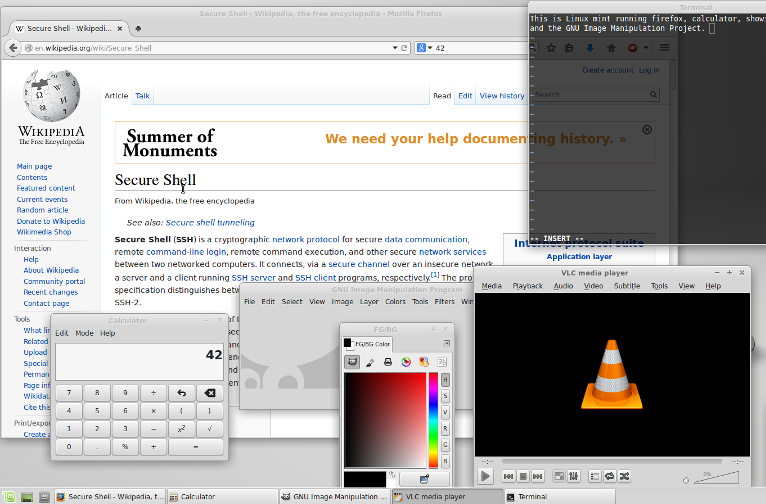

Teaser photo credit; By Benjamintf1 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35656954