This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

The Indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego were once relegated to historical oblivion. Now, archaeologists are helping them pursue deeper stories about their ancestors.

Text by Jude Isabella

Photos and video by Katrina Pyne

Spanish translation by María Paula Rubiano A.

Lea este artículo en español.

This article is also available in audio format. Listen now, download, or subscribe to “Hakai Magazine Audio Edition” through your favorite podcast app.

This is the end of the world: el fin del mundo, as the tourist brochures dub it; Tierra del Fuego, as it is known more universally; and home, as the Indigenous Yaghan people have called it for much of the past 8,000 years and probably longer.

The southernmost tip of South America is a jagged splay of islands, as if a careless god dropped a dinner plate. The Atlantic and Pacific Oceans meet here and the match is pitilessly stormy. The weather is mercurial—rain, hail, snow, and sun can beat the land within the span of an hour—but, on this summer’s day in February, it is sunny, warm, and windless. Kelp gulls natter, waves lap against a rocky islet, and a coppery tang—a blend of marine snails and algae—wafts across the reef where I’m helping gather limpets, scraping them off rough stones along the Beagle Channel.

Bucket full, I head off in José German González Calderón’s rowboat, in search of his crab pots. I am on the starboard oar, photographer Kat Pyne is on the port, and González Calderón watches our flailing from his seat at the stern with an expression that flits between willed neutrality and bemusement. Feofeo, his fluffy white dog, sits in the prow. Feofeo, Spanish for uglyugly, is cutecute and staring at us.

González Calderón, 58, solidly built, with a full head of gray-dusted hair, teases us: “Feofeo is bored; we are going too slowly.”

Everyone’s a critic.

González Calderón was, until recently, not supposed to exist—because he is Yaghan. Like the Palawa in Tasmania, the Sinixt in Canada, and the Karankawa in the United States, the Yaghan have the dubious distinction of coming back from the dead, their extinction declared by outsiders—Europeans and their descendants—for over a century.

Despite thousands and thousands of years of history, the story of the Yaghan, and other Indigenous cultures, has often emphasized one moment: the disastrous meeting with Europeans. And that’s what drives me here, an irritation that across the Americas, popular culture has focused relentlessly on that one point in time, and though significant, it’s like writing a badly abridged version of a multilayered story. A deeper truth lies buried, rich with a diversity of characters spanning time and place.

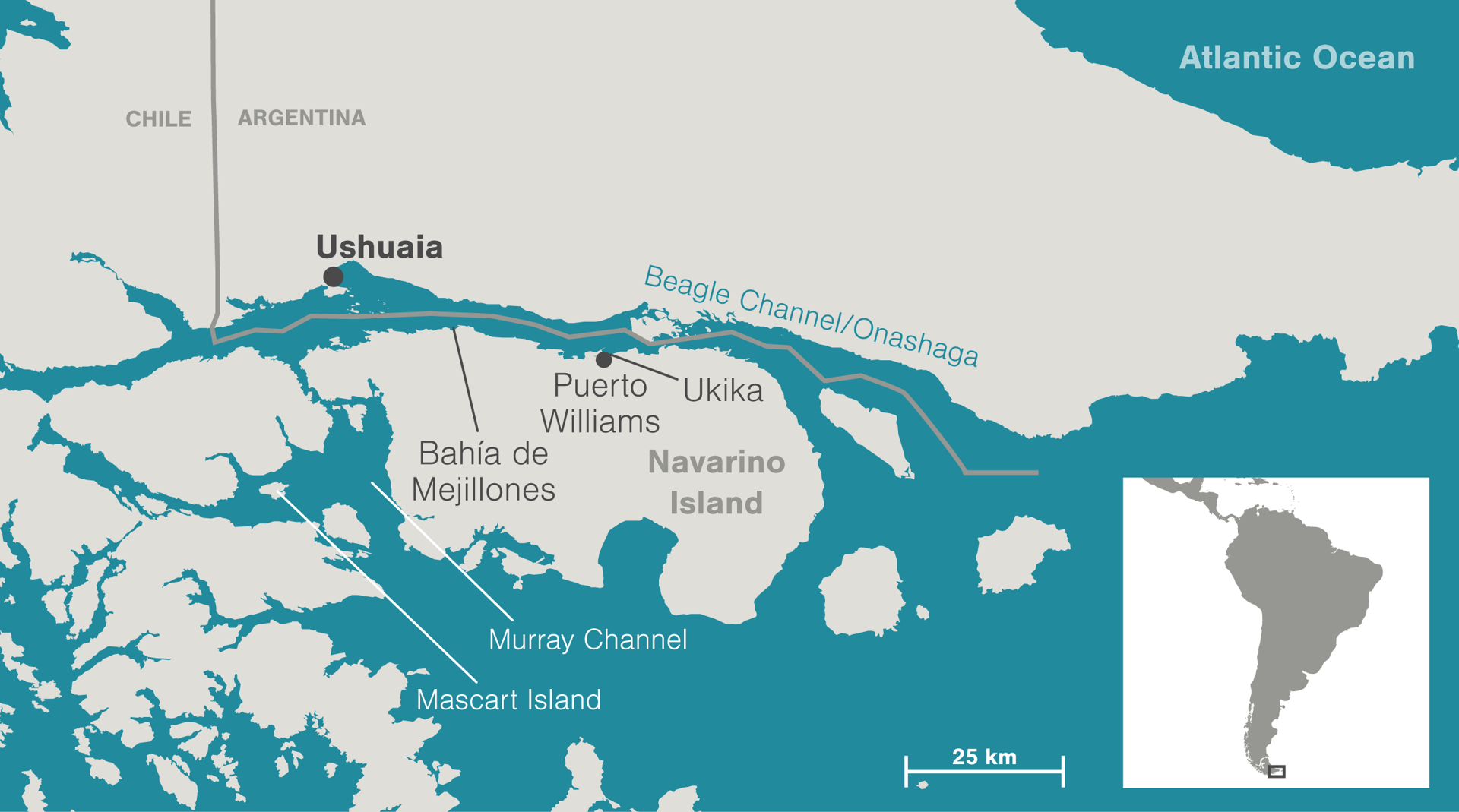

An Indigenous community that’s made Tierra del Fuego home for thousands of years, the Yaghan, currently lives on Navarino Island, Chile, and across the Beagle Channel (Onashaga in the Yaghan language) in Ushuaia, Argentina.

For the past few decades, archaeologists have been digging past the narrative told by European adventurers and chroniclers, those who killed some Yaghan, stole some, converted some to Christianity, and declared them all gone. They are searching the landscape more broadly than previous excavators, reinterpreting decades’ worth of data, and opening their minds to the evidence before them. They are unearthing in greater and greater detail a counter-narrative centered on the longevity and tenacity of the Yaghan—on how they went about making Tierra del Fuego, now split between Argentina and Chile, their home as the millennia spooled past. Joined with the oral histories of a proud and increasingly assertive Yaghan community, the archaeology aids in a people’s resurrection.

The story lies in the present, too. González Calderón has invited us to spend a couple of days with him on Navarino Island, a part of Yaghan territory, which once stretched across parts of Tierra del Fuego, practically to the tip of South America. The island, part of Chile today, has been Yaghan territory for thousands of years and it’s where most of the Indigenous community still lives.

Still high in the sky, the sun shimmers off the water as we land the rowboat at Bahía de Mejillones, Bay of Mussels. The bay looms large in Yaghan history. Shell middens—heaps of mostly mussel and limpet shells—dot the beach, extending meters deep. Standing vigil is the home of the bay’s last full-time Yaghan inhabitant, Benito Sarmiento, who, in the 1960s, resisted when the Chilean government moved the community and others of the archipelago to the outskirts of the island’s only sizable town: Puerto Williams, population 2,000, an hour’s drive east. Today, a few Yaghan keep cabins in Bahía de Mejillones, but they only visit. Sarmiento lived alone in the cove until his death in the 1970s. Sarmiento’s home, they say, serves as a reminder that the people will return.

González Calderón’s one-room yellow cabin perches on a hill above the road. The Argentine city of Ushuaia, across the Beagle Channel—called Onashaga by the Yaghan—seems like an easy canoe ride away, and we joke about paddling to the Irish pub there for a beer. The only drama comes from the mainland mountains in the distance, the jagged tail of the Andes, high enough to mistake for the ramparts of heaven. A light that evokes something divine reflects off ice saddled between the ridgeline’s stony spires.

We chat and gaze across the channel. González Calderón scrapes the limpets from their shells, chops seaweed, and adds some vegetables packed for the trip into a pot to make soup. It has a lovely saltiness that only the ocean can impart, and every once in a spoonful, a little smiley face, a limpet, peers up in seeming disbelief through strands of seaweed.

González Calderón’s mother, Úrsula Ercira Calderón Harban, was born in Bahía de Mejillones in 1923, and he spent his early years on nearby Mascart, a small island across from a bay where the Yaghan massacred missionaries in the 19th century. Úrsula died in 2003. Her sister Cristina Calderón Harban remained as the matriarch of the community on Navarino Island until she died, age 93, this past February. She lived surrounded by family in Villa Ukika, the Yaghan village skirting Puerto Williams. Cristina wove baskets, told stories, and kept the Yaghan language alive.

As we sit and sip soup, a friend of González Calderón’s, Jaime Ojeda, a Chilean marine ecologist, tells me that Cristina was sick of journalists. Ojeda has known the Calderón family since 2008, when he lived on Navarino Island, researching seaweed and mollusks for his master’s thesis. He arranged this trip to Bahía de Mejillones. Cristina, Ojeda says, had to endure endless requests for interviews and ersatz stories of her fashioned by outsiders: the last speaker of a language, the last to remember a dead way of life, the last of the “true” Yaghan. This broken “last of” narrative sticks like gum to a shoe, embedded in the sole. Even tourists sought out Cristina, hoping for a last-chance-to-see moment they could post on social media.

The Yaghan past is present everywhere on Navarino Island, in the shell middens, in the bounty of the ocean, in the animals and mountains that feature in stories, in a carefully curated museum, and in the people themselves. But in today’s currency of words and pictures, the tourists seemed to want to capture Cristina as an embodiment of an ancient people. They wanted her to validate the stories that Eurocentric voyeurs spun of exaggeration, assumption, insularity, and willful ignorance. It’s a faulty narrative that began in 1519.

***

Ferdinand Magellan sails from Spain in that year, across the Atlantic and through a strait at the tip of South America into the Pacific, the first European to do so. When he reaches the southern tip of South America, smoke blankets the shoreline. Magellan names it the Land of Smoke, Tierra del Humo. He sails on. The king of Spain, however, declares that where there is smoke there is fire, and renames the land the catchier Tierra del Fuego. The name—encapsulating a brief moment, a scene misunderstood and little contemplated—sticks.

Almost 60 years later, after weeks bashing around the Southern Ocean, storm-tossed sailors of the Golden Hind, captained by English privateer Francis Drake, spot a bay. People materialize out of the bush. A priest onboard scribbles notes about canoes filled with men and women paddling from island to island, children wrapped in skins hanging on their mothers’ backs. The canoes are marvelous, he writes.

And so begins the journaling or, in anthropology-speak, the ethnography. Written mostly by white male Europeans in English, French, Italian, German, Dutch, and Spanish, the number of words spilled on the Yaghan is astounding. The Europeans are by turns admiring and dismissive, but mostly they’re obtuse.

The Dutch arrive as early as 1616. In February 1624, eager to engage in battle against the Spanish Armada in Peru—apparently a necessary step toward world domination—they park their fleet in various bays of islands south of Navarino Island. In one, where five ships anchor, sailors row to shore in search of water and firewood. After they fail to return, their compatriots find five corpses and two survivors on the beach. Another 12 sailors are missing. The Yaghan have dispatched them with spears and bows and arrows. The Europeans label the Yaghan cannibals, a calumny that will dog them for 250 years.

The decades tick by, with visits from Englishman Captain James Cook in 1769 and 1774. He calls the region’s people “a little, ugly, half-starved beardless Race,” sprinkles their territory with the name Desolation—as in Cape and Island—yet gushes about the rich marine life, particularly whales and seals. Soon after, the first whaling boat sails around Cape Horn into the Pacific Ocean and sperm whale territory. Legendary tangles with that species—perhaps the most difficult whale to capture—become the inspiration for Moby-Dick. Whale oil fuels the Industrial Revolution. Exploration fuels exploitation.

The Europeans steal people, bring them back to Europe, display them or try to civilize them, then return them home. On his first voyage to Tierra del Fuego in the late 1820s, Captain Robert FitzRoy penetrates Onashaga, the channel at the heart of Yaghan territory, in his brig-sloop, the Beagle: the Beagle Channel will thereafter carry that naval vessel’s name. FitzRoy absconds with four people—Fuegians, he called them—and brings them to England. One dies.

On his second voyage, in 1831, FitzRoy returns with the three surviving Fuegians and a young Charles Darwin, who approves of the manners the trio have gained living as the English do—in boarding schools. Their English names are Jemmy Button, Fuegia Basket, and York Minster. Their names are Orundellico, Yokcushlu, and Elleparu. The Yaghan Darwin meets on Navarino Island, in contrast, revolt him. The man whose keen observations and open mind launch a scientific revolution writes, “They are such thieves & so bold Cannibals that one naturally prefers separate quarters.” Darwin is not fine hobnobbing with his Fuegian shipmates’ relatives. He thinks they eat their grandmothers.

Europeans are Energizer bunnies, nothing deters them: not months spent on cramped wooden sailing ships, not treacherous seas, not bad weather, bad food, or risk of death. They keep coming. As in zombie movies, the plot never changes, only the actors. European explorers come and go—the way dream monsters do—and their impermanence makes them manageable. Next up? Missionaries in search of heathens. Cue the low note of doom, an ominous hint that life, for the Yaghan, will now change dramatically. God can throw anyone’s universe into chaos.

Until now, the Yaghan are masters of their fate. Fires keep them warm—on land and in their bark canoes—and so probably does the sea mammal fat smeared on their skin. They paint their bodies with red ocher, black charcoal, and white clay. Clothes—seal-skin capes, loincloths—are minimal. The land gifts them tall, straight trees, southern beech that they strip of bark to craft canoes. The ocean offers endless bounty: sea urchins, mussels, limpets, cormorants, penguins, fur seals, sea lions. Sometimes the sea bestows more than any one tribe can wish for—a whale beaches itself, an opportunity broadcast through smoke signals to neighbors. Kindness and generosity are virtues. Uplifting oral histories guide the living with takeaways like “courage conquers all” and “the impossible is made possible.” Spirituality embraces the nonhuman world: to mock animals and water spirits is dangerous. And as we all might be, the Yaghan are suspicious of hairy men living without women.

But by the mid-19th century, a Christian organization in England, having heard the Yaghan are docile and untarnished by popish priests, raises funds to send a mission to convert them. Saving souls is a competitive Christian practice. An early mission, composed of seven men, starves to death, though not before killing a few Yaghan. Later, on Navarino Island, the Yaghan massacre an all-male mission. Subsequent efforts to convert the people succeed, especially when the missionary Thomas Bridges, who became fluent in the language, takes over and brings his wife to Yaghan territory on what will become the Argentinian side of the Beagle Channel.

With the mission comes the Argentine navy, a declaration of Argentine sovereignty, and the measles. In 1888, the Bridges family witnesses an epidemic that nearly wipes out the Yaghan. In a memoir, Uttermost Part of the Earth, Thomas’s son Lucas writes:

“They were a dying race, who seemed to know it.”

Once ringing, there’s no stopping the death knell.

Martin Gusinde, an Austrian priest and ethnologist, visits four times between 1918 and 1924. He establishes relationships with the people, particularly Nelly Calderón Lawrence, an ancestor of González Calderón, and dives into the culture—the Yaghan museum on Navarino Island bears his name—describing rituals and mythology in danger of being extinguished along with the language. Gusinde estimates a population of roughly 70 and he, too, falls into the notion that the people will soon cease to be.

In 1934, a former US ambassador to Chile announces the Yaghan “all but vanished.” In 1977, in a bestselling book, In Patagonia, English writer Bruce Chatwin declares he has met the last Yaghan, Grandpa Felipe. In 1986, a Chilean journalist publishes a book about a Yaghan elder, Rosa Yagan: The Last Link.

The written record, centuries deep, becomes the narrative, limited and blinkered by the lens of a vastly different culture. There is a different story. Or, more precisely, stories.

In Argentina, across the Beagle Channel from Navarino Island, within an hour of my arrival at an archaeology dig a couple of weeks before my visit with Gonzáles Calderón, the weather alternates between rain, sun, and hail. Less sheltered than the bay on Navarino Island, wind is a constant companion here.

A white tent covers a large rectangular hole a bit bigger than two average-sized parking spaces, a four-meter-by-eight-meter archaeology excavation. A grid made from string overlays the dig and divides the site into 32 square meters. Archaeologists crouch before the squares, using trowels to scrape away a thin layer of dirt, depositing the soil into buckets. I grab a full bucket and empty it on a screen laid across sawhorses outside the tent. Next, I scoop water from an algae-ringed pond and splash it on the screen, sieving out the dirt until only rocks remain, some of them artifacts. A practiced eye can tell the difference.

This is gumboots, rain pants, and slicker work: one bucket of water thrown on a screen with one bucket of dirt equals one mud pie. The smell, however, is sophisticated: peaty Scotch with a hint of manure.

While the roughly 100 Yaghan alive today continue to assert their place in the here and now, archaeologists are in pursuit of a deeper and broader story of their ancestors who made the land and sea their home since possibly as far back as the end of the last ice age. Atilio Francisco Zangrando and Angélica Tivoli from the Centro Austral de Investigaciones Científicas del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CADIC) in Ushuaia, the Argentinian capital of Tierra del Fuego, lead the archaeology team. They also hope to dig past the oldest date recorded for the Yaghan in the Beagle Channel—almost 8,000 years before present.

Francisco Zangrando and Tivoli met at the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina in 1999 and have worked together as colleagues since 2010 at CADIC. Physically, they are a study in contrasts. Francisco Zangrando is tall and broad, gray speckles his curly black hair, glasses frame his eyes; Tivoli is petite, with fine features and blond hair. But they both wanted to be archaeologists from the time they were kids in the 1980s and read a newspaper feature about the “canoe people” and the archaeologists who were beginning to unearth their story.

A tent protects the archaeology site at Estancia Moat from the vagaries of weather along the Beagle Channel/Onashaga—within the span of an hour, it could rain, hail, or even snow. Atilio Francisco Zangrando, left, coleads a team of archaeologists from the Centro Austral de Investigaciones Científicas del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CADIC) in Ushuaia.

The story that captured the imaginations of Tivoli and Francisco Zangrando was of an ancient people so well adapted to their environment that they thrived for 6,000 years, until the arrival of Europeans, relying on a simple toolkit and a stable seafood diet. They fashioned harpoons and spears to hunt sea lions, fur seals, and fish. They danced their canoes across the Beagle Channel, gathering mussels and limpets, creating jewelry from shells and bones. They buried their dead.

The article explained that the story was being revealed, since 1975, by archaeologists Luis Abel Orquera and Ernesto Luis Piana. Anywhere along the Beagle Channel that a canoe can land, the archaeologists found heaps and heaps of shell middens. They excavated many, finding well-preserved animal bones, blades, harpoons, and jewelry. In scores of papers in English and Spanish, the archaeologists rewrote the centuries-old Eurocentric narrative of the Yaghan, whom the researchers dubbed the canoe people.

Francisco Zangrando, foreground, has excavated along the Beagle Channel/Onashaga since 1998.

Tivoli tucked away the story. Francisco Zangrando, age 11, had other ideas. At dinner one night—and it’s night, not evening: Argentinians dine at 10:00 p.m. or later—Francisco Zangrando tells the team at base camp the story about his introduction to archaeology. Base camp—where the team sleeps, eats, and banters—is a disintegrating ranch house, maybe 100 meters from the excavation. The ranch was once home to the Lawrences, a missionary family that arrived in Tierra del Fuego in the late 1800s, along with the Bridges. Serving the beef he just cooked over a wood fire on a brick grill—traditional Argentine asado—Francisco Zangrando explains that his 11-year-old self simply found Luis Abel Orquera’s name and address in the phone book and cold-called him.

Orquera invited the boy to visit the university. He went, with his father, and told the archaeologist he wanted to participate in an excavation. Orquera suggested he wait, but keep in touch. They met again during Francisco Zangrando’s first year at university. The day he turned 21, in 1998, Francisco Zangrando realized his boyhood dream, excavating a shell midden along the Beagle Channel.

Tivoli deadpans: “I was a normal child.”

Angélica Tivoli, coleads the team at the archaeology site in Estancia Moat, which is dated to over 5,000 years ago.

As PhD candidates in the early 2000s, Francisco Zangrando and Tivoli dug deeper into their dream work and began to wonder if archaeology had a vision problem. In the 1970s, when Orquera and Piana had first launched into uncovering the Yaghan’s ancient past, colonial culture was starting to crumble, yielding to an era of relative inclusiveness. The Yaghan excavations, from the start, were about laying aside old European narratives, looking for material clues, and interpreting the past based on hard evidence. But the evidence came only from shell middens concentrated along the sheltered central part of the Beagle Channel’s shoreline.

For Tivoli and Francisco Zangrando, that lens has become too small, the framing too focused. The portrait of a place and its people, though vigorously reimagined through 50 years of archaeology, has largely remained static, like those old black-and-white photographs snapped in colonies around the world of grim-faced Indigenous people posing in traditional dress or settlers displaying their Sunday-best clothes. It’s tempting to ascribe people traits based on a few moments frozen in time, to build a narrative from the documentation in hand and forget that life is a messy enterprise and parts of it elude our shovels and trowels.

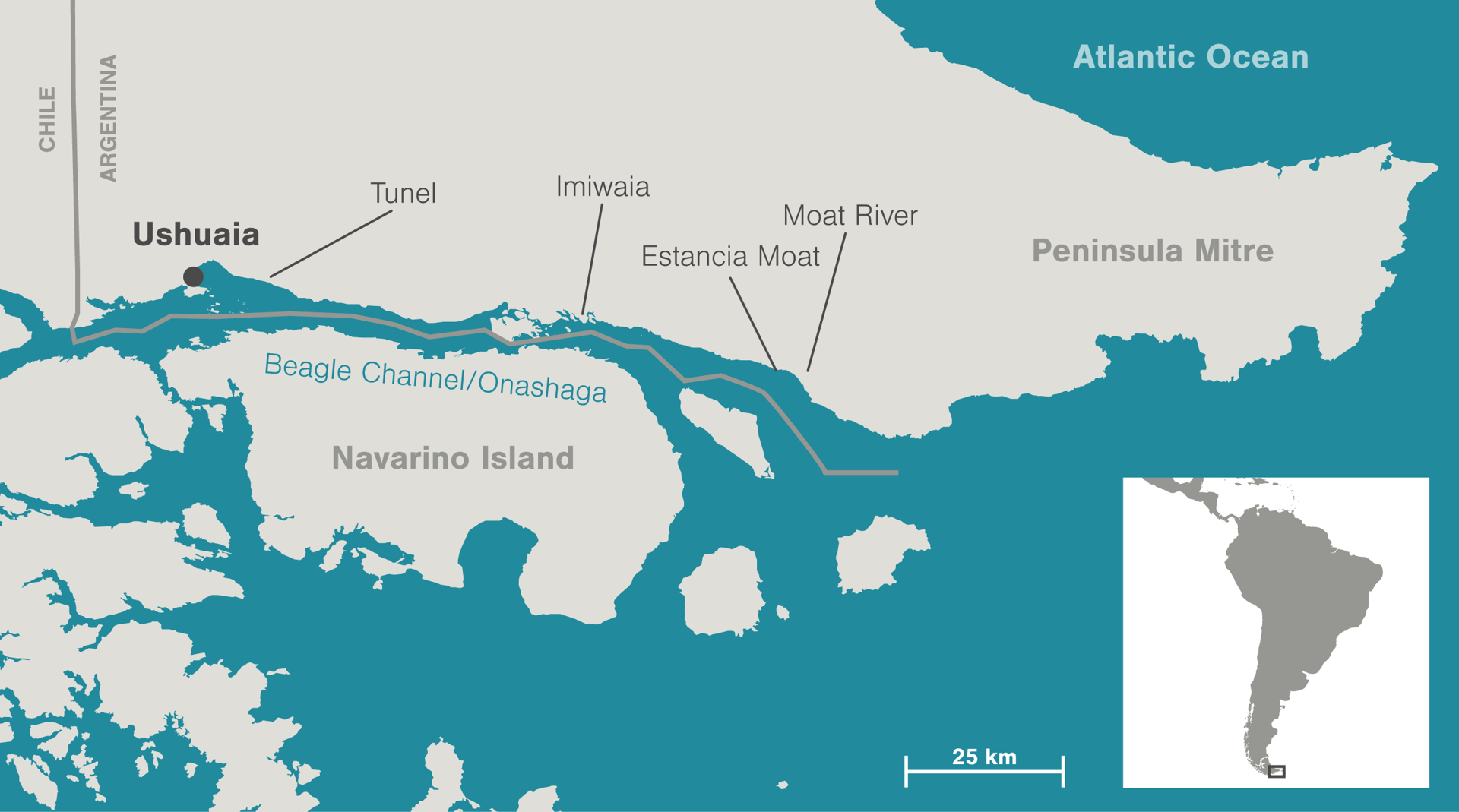

The Yaghan’s past as well-adapted canoe people is celebrated thanks to archaeology, but the arc of the story is still slightly off. Not wrong, it’s just that we are reading one chapter in a series of books with many missing volumes. And this is one reason for the dig here by the Lawrences’ former house—a ranch called Estancia Moat (pronounced “moe-aught”). It’s different from all the other sites along the protected Beagle Channel: it’s not a shell midden atop a hummock, but rather a muddy flat on the coastline edging eastward into the stormy Atlantic Ocean.

***

Finding the site at Estancia Moat in the first place took a fresh perspective, a new set of eyes. In 2014, Hein Bjartmann Bjerck, a Norwegian archaeologist working with Francisco Zangrando and Tivoli’s team, excavating shell middens near the ranch, went for a stroll. The day was mostly sunny and, as usual, windy. Bjerck climbed a drumlin, one of the hills that look like giant, half-buried eggs. Drumlins, formed below retreating glaciers in a warming world, speckle the landscape all along the Beagle Channel. Bjerck, however, was looking beyond the shell middens; he was thinking like a Norwegian.

In Norway, shell middens are rare—early people probably relied on fish, not shellfish—so archaeologists look for other clues to potential dig sites. Their gaze goes deep, seeking what is hidden. Bjerck scanned the ocean, the ranch house, and another little house closer to the water, where gauchos live and work. Both houses sit on a plain. Before the glaciers melted and the land—relieved of the icy weight—rebounded, sea levels were higher: Bjerck reasoned that water would have lapped over the plain, creating a shallow bay and beach, a reliable harbor sheltered by the drumlin.

At the base of the drumlin, gauchos had dug holes for fence posts. Bjerck walked down and ran his fingers through the piles of dirt and found some flakes from the manufacture of stone tools. He dug his own hole, then a test pit, and found a lot more flakes. The archaeologists eventually dated the pit’s charcoal layers—probably an ancient hearth—to reveal people on the landscape over 5,000 years ago. Not earlier than 8,000 years ago—Tivoli and Francisco Zangrando’s holy grail—but it was intriguing precisely because it came from a site that was not embedded in a shell midden. Perhaps it would tell a different story? The alkaline nature of shells is fantastic for preservation of organic matter, but focusing on shell middens skews the data: it’s like describing modern lives based on what’s found in the kitchen, missing the piano in the living room, the books on the shelves, or the bicycles in the basement. Bjerck’s pit marked a fresh start.

“As soon as we started to work with Hein [Bjerck],” Tivoli says, “we started to develop this different way of looking at the landscape and searching.”

On this project, it meant looking beyond middens and into the muck of Estancia Moat.

***

A few of us take a break to climb the drumlin that rises from the muck. We dig a test pit at the top, in a shell midden. People congregated on drumlins: think of it as building a community hall at the top of a hill—the view is excellent and water drains away. Drumlins were also good lookouts, Tivoli says, and Indigenous communities would light fires at the top to send smoke signals to each other. A stranded whale was an event to be shared with neighbors. So too, probably, was the appearance of an enormous wooden boat.

A warm north wind picks up, and we peel off jackets and sweaters. The archaeologists set up a one-by-one-meter square, then cut away its mat of vegetation, setting it aside. Next come trowels. Within 30 seconds, limpet shells pop out. Soon after, we uncover cormorant bones, a penguin wing bone, a marine mammal backbone, a mother lode of bones from guanacos (wild camelids), and stone flakes.

“A penguin bone, that is so great,” Iain McKechnie, a visiting archaeologist from coastal British Columbia, says in wonderment. His BC sites release stone flakes, hearths, and tiny fish bones. Yet he scoffs at the midden-ites who fail to move their archaeology beyond the shell heaps. Over lunch and dinner, McKechnie has been exclaiming, “Sites before shell middens!” A mantra perhaps, or a watchword embodying a guiding principle for archaeologists: get out of the shell midden and get dirty. Nicole Smith, a Canadian archaeologist married to McKechnie, laughs, and in the kindest way, rolls her eyes.

Excavating shell middens, as satisfying as it may be, has another vexing issue: the bottom is not necessarily the bottom.

Smith understands a shell midden’s limitations; she has spent years excavating them on Haida Gwaii, off Canada’s northwest coast, where the Haida people have lived since at least the end of the last ice age. “There are layers below middens in Haida Gwaii where it looks as if the carbonate dissolved,” Smith says. Earth eats shell: groundwater is so acidic that over hundreds or thousands of years, shells decompose. On Canada’s west coast, there are thousands of shell middens, she acknowledges, but the oldest sites are not found within them. “That’s the problem of these old dates below shell middens, with no shells around,” she says. “The shells dissolved perhaps, but why is there shell midden above? Does a certain amount of accumulation need to happen before it’s preserved? Or is it a time factor? Eventually, will the whole midden disappear, too?”

The two oldest dates along the Beagle Channel—and the second- and third-oldest dates for Tierra del Fuego as a whole—come from the bottom of shell middens excavated during that 1998 dig, and by Orquera and Francisco Zangrando between 2010 and 2013. Dated to around 8,000 and 7,000 years before present, these bottom layers have yielded few artifacts but include tools found nowhere else in Tierra del Fuego: beveled and polished basalt chisels and unusually shaped projectile points. The archaeologists found some poorly preserved bones, too, which may belong to sea lion and guanaco. The people who left these artifacts appear to have been landlubbers, without the harpoons or spear points canoe people relied on to hunt fur seals and sea lions or fish from boats. Above those finds, the shell midden begins, revealing the rich narrative of the canoe people and the blades, harpoons, and jewelry that flesh out the picture of prosperous seafaring communities, so well adapted that they changed little over 6,000 years. Those two older dates are mystifying, though—where do they fit into the story? What are the archaeologists missing?

Archaeologists contemplate evidence while keeping in mind that they have no idea what they have not found. The absence of evidence, they know, is not evidence. Take, for example, dog bones. Never have archaeologists excavated a dog bone in Tierra del Fuego, Francisco Zangrando says. But the Yaghan had dogs. They appear in Yaghan stories. Anthropologists reported dogs, too, and considering that it takes time to domesticate a canid species, the Yaghan could have started doing so long before the 16th century. One stuffed specimen in a regional museum has yielded DNA suggesting that a native fox species gave rise to Yaghan dogs.

Climbing out of a shell midden, where a scientist is almost guaranteed to find artifacts and animal remains, and descending into a pit that could muddy the research—like those earliest dates that bestow no answers, just more questions—takes some coaxing. “Our team has been doing archaeology for the last 45 years but focused too much on shell midden formation,” Francisco Zangrando says. Shell middens have yielded a bias, he believes, that overweights practices of the past few millennia, restrains the research geographically, and possibly ignores the beginnings of human activity in Tierra del Fuego. When did people adapt to a maritime lifestyle? What lured them into the sea?

The oldest sites along the Beagle Channel/Onashaga were found at Imiwaia and Tunel. At Estancia Moat, the archaeology team from CADIC hopes to find older evidence of people. Map data by OpenStreetMap via ArcGIS

So the muddy flat at Moat is welcome for the information it may yield about a past more distant than shell middens tend to reveal. But Moat’s geography is another reason the team is excited about it: this is the oldest date and non-midden site found so far in a sort of no man’s land of excavation, between the sheltered central Beagle Channel and Peninsula Mitre, which juts like the turned-up toe of an elfin boot into the Atlantic. A cloud, one that obscures a clear view of the past, still lurks over the peninsula, as it does over a lot of sites in Tierra del Fuego: the written historical record has an almost insurmountable lead over the archaeology record. European chroniclers arrived in the 16th century, archaeologists not until the late 20th century.

***

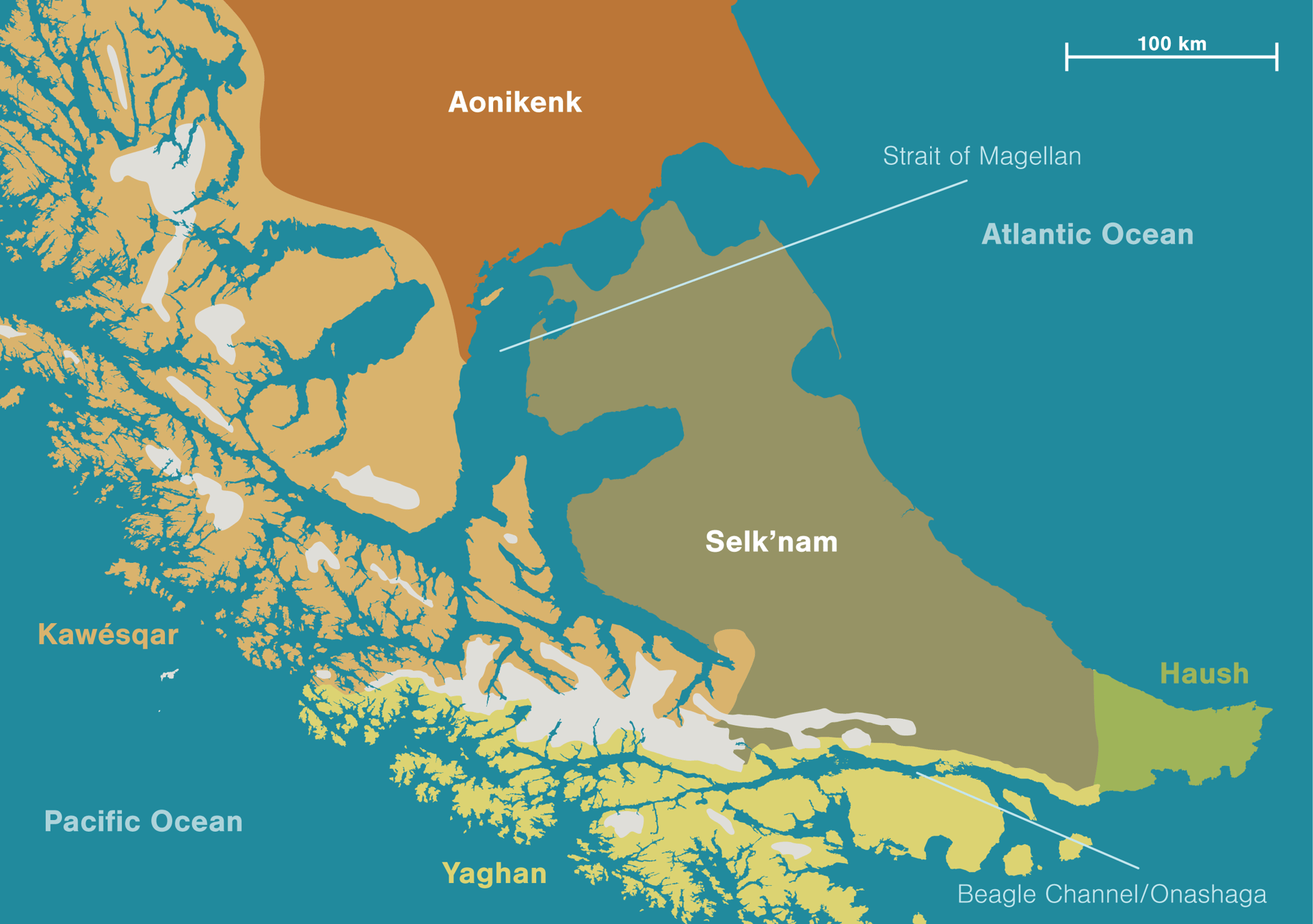

Peninsula Mitre is the kind of place that most people visit by browsing Google Earth or by watching a surfing video. A boundary peculiar to our time—a reliance on specific tools, such as electricity, combustion engines, even lighter fluid—keeps people away. Not a lot of archaeologists have visited the peninsula. An anthropologist, Anne Chapman, hiked through in the 1960s and early 1970s, collecting artifacts from shell middens along the shoreline. In the 1980s, a few archaeologists dug into a few beaches. But mostly the story, until recently, has rested on historical accounts. From the writings of Gusinde—the Austrian ethnologist—and Chapman, we know something about the people who lived there: the Selk’nam, a land-based society, and the Haush, who tuned into land and sea.

Flavia Morello is an archaeologist at the University of Magallanes in Punta Arenas, Chile. She’s excavated shell middens on Navarino Island and along the Strait of Magellan, over 200 kilometers north of the Beagle Channel. She is of the same cohort as Francisco Zangrando and Tivoli; she, too, has been questioning the orthodoxy of earlier studies of the Yaghan and other Fuegians. The tyranny of ethnography has a lot to do with narrowing researchers’ vision, she believes.

“In Tierra del Fuego, the first thing they teach you as a student: if you have a shell midden, they are marine hunter-gatherers, and if you have mainly guanaco, you have terrestrial hunter-gatherers,” she says. “But there are so many instances of mixing.”

Like the Haush.

On Peninsula Mitre, the Haush were both terrestrial and maritime, and they never fit tidily into anybody’s model, Morello says. Looking at the land- and seascape, why would they? The Atlantic Ocean pounds against the shoreline; it’s windier and less sheltered than the Beagle Channel. Geographically, it would make sense to shuttle from shoreline to the protection of the forests. The Haush hugged the peninsula coastline, hunting guanaco at the inland reaches of their territory and catching seal and sea lion along the rocky shore, no boat necessary. The Selk’nam were spread from the Strait of Magellan to Haush territory, living mostly inland, mostly hunting guanaco.

In a time before Europeans, Tierra del Fuego was home to four Indigenous groups that had ties to other communities on Patagonia, the closest being the Aonikenk. The Yaghan and Kawésqar adopted a maritime lifestyle. The Selk’nam occupied most of Isla Grande north of the Yaghan, and the Haush inhabited Peninsula Mitre and adopted a mixed terrestrial/marine lifestyle. Map data by Prieto, et. al. 2019

In the past couple of decades, archaeologists have been readjusting their perspectives on the tidy boundaries of who lived where and when. By pushing the geographic scope to Estancia Moat and the peninsula, Francisco Zangrando and his colleagues are zooming out, from a close-up of neighborhoods to a panoramic view of a whole region, and watching how people lived and interacted over time. About 10 years ago, they found traces of the Yaghan on the peninsula and beyond.

“We have a movement of the [canoe] people to the peninsula 2,700 years [ago],” Francisco Zangrando says. And more recently the team has found Yaghan harpoon points from the peninsula’s south coast dated to 5,000 years ago. “That is dynamic. It is something new. You don’t have one kind of hunter-gather here and another there.” The movement of the Yaghan was a big leap across the landscape that archaeologists had missed.

Once established on the peninsula, the Yaghan shove off from there, as well. They soon paddle to an island 30 kilometers across rough waters, presumably to reach the same animals they hunt and harvest on the peninsula and in the Beagle Channel: colonies of sea lions, fur seals, penguins, cormorants, albatrosses, and mussels. Why make the dangerous crossing, then? A warmer, drier climate may have weakened the prevailing westerly winds and made them more predictable.

On the peninsula, new archaeological digs and a re-examination of the evidence show people mixing it up. Information gets passed around the communities of the Beagle Channel and the peninsula. The people borrow ideas. They share knowledge. You can see it in their daily activities. Some 6,000 years ago, the people of the peninsula are decorating bone harpoon points with cruciform bases and beads with curved, rhythmic incisions. Over in classic canoe people territory, in the central Beagle Channel, the people are doing the same, decorating their harpoon points and beads. “It’s very nice decoration, very nice art, and it takes a lot of time,” Francisco Zangrando explains. “And then that kind of decoration disappears.” By 3,000 years ago, both on the peninsula and in the Beagle Channel, they’re done with art on harpoon points, and they drop the cross. They’re fashioning harpoon points with simple shoulder bases, a design they’re still using when Europeans arrive. Another technological change: they’re knapping stone—metamorphic rocks—instead of bone, into spear points.

Harpoon points with a cross base made on cetacean bone from the Tunel I site that date to between 4,590 and 6,470 years ago.

Food preferences change, too. Across the region, people are mad about seals and sea lions some 6,000 years ago. Then 5,000 years ago, they’re still eating sea mammals but go big on guanacos and seabirds, and in the last 1,000 years, they’re more into fish. There’s no hint that, during that time, they depleted a resource and moved to the next. It seems a matter of preference: food fads. The people were anything but living a static existence for thousands of years—they created and adapted and shared information across time and space.

For millennia, interaction and information flow freely across the region between terrestrial people and marine people. They trade obsidian from hundreds of kilometers away on mainland Patagonia to the Beagle Channel, for a while, then there’s a gap, and obsidian reappears as a trade item in the north. When people trade, they talk. Remember that seemingly random Yaghan slaughter of 17 Dutch sailors back in 1624? Word had probably traveled from the Magellan Strait, over 200 kilometers away, to the Beagle Channel, about a massacre 25 years earlier: foreign sailors had killed as many as 40 people from the Selk’nam tribe. The Yaghan, in 1624, may have been warned to strike first or, as Captain FitzRoy surmised, they were taking revenge on behalf of their neighbors.

“We see the changes, but how you interpret those changes … none of us has the correct answer,” Morello says. “It’s just going to keep evolving forever.” It would be nice, she muses, if you could pick up the record and read archaeology as a book, from cover to cover. But if archaeology were a book, it would be one that had been dropped in a bathtub full of water: the pages would be fused together, and prying them open would destroy what you’re hoping to read. Archaeologists have to coax open their fragile book.

***

Mucky Estancia Moat is especially clumpy; the mud reveals so little, but it’s worth the effort. It’s a hinge point. Compared with the central parts of the Beagle Channel, the region is more exposed and more boisterous weather-wise, the mountains are lower, and the marine influence is stronger. But there is a trade-off. Before 5,000 years ago, Moat was mostly grassland, then as the climate changed, peat bogs and patches of evergreen forests colonized the land, resulting in a more guanaco-friendly landscape than the deciduous southern beeches used for canoe making. Moat River runs 50 kilometers from an interior valley to the coast, a path easily followed by all sorts of animals, including humans. That route made it “easier to interact between the coast and inland,” Francisco Zangrando says. Estancia Moat is on the shoreline, but the frequent hunting in the forests is evident from the guanaco bones littering the middens on top of the drumlins that surround the site, with dates ranging from 1,000 to 600 years ago.

There is a lot of hope riding on Estancia Moat. Will it reveal something new, something the shell middens cannot?

Excavation at Estancia Moat is muddier than at most sites along the Beagle Channel/Onashaga because it’s not a shell midden. The dig revealed ancient tools never before found in the region—stones with holes picked out of the middle.

During a sunny moment on a summer day, an undergraduate student on his first dig unearths a palm-sized doughnut-shaped stone ring. More digging unearths three more doughnuts, one broken, within two square meters. Smith, McKechnie, and a visiting Norwegian archaeologist immediately identify that the stone doughnuts are probably weights for fishing nets, a technology ubiquitous around the world.

Finding them along the Beagle Channel is a first.

“The interesting thing is, it is not just one [stone ring],” Francisco Zangrando says. He’s leaning over, carefully brushing dirt from one of the doughnuts. “We have at least three or maybe four. So, wow. That gives you some kind of context for discussion.” Francisco Zangrando and Tivoli are nonplussed, even though it’s unusual to find a clutch of tools together as if they were just laid aside for a moment.

But the rings are also unusual for how they stand out from all the other stone artifacts unearthed here. If artifacts could vamp, these stone doughnuts, three still partly encased in their muddy tomb, are strutting—more glamorous than stone flakes, cracked hearth stones, and the charcoal from spent fires. “Look at us,” they might say.

But Francisco Zangrando won’t even say that the carved stones are definitively net weights, he’s all about data and hard evidence. “They could be some kind of net weight, yeah, why not? But we have to find a way to support that.”

Tivoli is circumspect, like Francisco Zangrando, as she picks one up for inspection. “The object was left behind for whatever reason, and it was on a beach, you can say that [about it].”

Yet imagination is part of the process, too, and I have no problem surmising: almost 5,000 years ago, someone held the stones—carved doughnuts—in his or her hands. The person’s family arrived in a canoe, perhaps, shouting for help as they pulled a heavy, dead fur seal out of the boat. The person set the stones down, hurried up the beach, and forgot about them.

As exciting as the stone doughnuts are, it is a discovery later—on the last day of the season’s excavation—that fills the team with hope: below the 5,000-year mark, at an older layer, they find a hearth, charcoal bits, and bone fragments, datable material. The ancient moment they’re searching for—a site older than the 8,000-year mark—just got closer.

***

The days on Navarino Island, across the channel, are sunnier and warmer than at the dig at Estancia Moat, with its influence from the Atlantic Ocean.

With González Calderón, we string a net across a natural fish trap on the beach and catch two robalo, the Patagonian blennie or rock cod. Sometimes, González Calderón says, he snags a salmon that strays from a fish farm hundreds of kilometers north, a reminder that boundaries are often imaginary and cultural. We’re fools to believe otherwise.

González Calderón sets a net for robalo (Patagonian blennie) in a natural fish trap in a bay near Bahía de Mejillones.

Ojeda, the marine ecologist, goes snorkeling for sea urchin, while the rest of us sit on the beach. We collect mint for tea and wood for a fire. We sit late around the fire, looking at the stars, eating dinner, chatting. In the middle of the night, awake in my tent, I hear voices, Ojeda and González Calderón, still talking.

But now it’s time to go. We drive to Puerto Williams, passing the Chilean naval base fronting the shoreline and crossing a bridge over the Ukika River into Villa Ukika, where candy-colored houses are sprinkled like confetti across an area smaller than a city block.

Most of the people who identify as Yaghan, including González Calderón, live there. They are Chilean citizens with jobs, families, and hopes for the future. Some are also basket weavers, foragers of traditional plants and seafoods—urchins, limpets, fish. They practice the Yaghan language. And they are activists. They protect their waters—Onashaga, the Beagle Channel. Most recently, they mounted a spirited opposition to the salmon farming industry’s bid to install net pens in the channel.

At a presentation at the Yaghan museum in Puerto Williams the next day, González Calderón, a former president of the Yaghan association on Navarino, and two other Indigenous leaders, a Yaghan from Ushuaia and a Selk’nam from Rio Grande on Peninsula Mitre, present on a number of issues touching on cross-cultural relations. About 30 people, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, cram the room, some holding smartphones aloft. A camera crew records it all.

The leaders talk about their visit to Bayonne, France, for a cultural festival about Indigenous peoples, not an entirely successful trip. The re-creation of a sacred initiation ceremony by a couple of artists was insensitive. They couldn’t view the bones of their people, kept in a Nantes museum, during the trip, nor listen to recordings of an Indigenous elder they had hoped to hear. The three also talked about the marketing of their culture in Chile and Argentina—a beer named Yaghan, fridge magnets based on their art, street signs with images of an initiation ceremony—and how the border between the two countries, slicing through the Beagle Channel, has made it difficult to maintain relationships with each other.

For thousands of years, borders were more fluid. The Yaghan danced across the waves from bay to bay. They hunted, they fished, they traded with their landlubber neighbors, taxiing them across the channel when necessary. The European explorers wrote of seeing over 100 canoes. Today, traffic on the channel includes navy boats, cruise ships, private sailboats, and scientific expeditions, but no canoes: it’s easier to fly to Navarino Island from Punta Arenas, Chile, than to board an expensive ferry that caters to tourists from Ushuaia, Argentina.

In the Argentine city of Ushuaia, the Yaghan receded more quickly than on Navarino Island in Chile. Argentinians had no idea the Yaghan people lived among them. Near war between the two countries severed much of the contact between the communities. Before the border skirmish, the Indigenous communities on either side of the Beagle Channel/Onashaga would meet often.

As archaeologists begin to see the past more holistically—piecing together a story of highly mobile people living together, sharing knowledge across an archipelago stretching closer to Antarctica than any other landmass—they throw into relief the constraints that today’s artificial boundary imposes on the Yaghan and their neighbors. The political border restricts their way of being in the world—rooted but not fixed—and it must chafe. The point is: this is a dynamic place and a dynamic people. Once, they roamed far and wide. We put them in various boxes narratively, and governments put them in boxes geographically.

The Yaghan, though few in number today, never doubted their identity or their own existence. Their stories say this place has been home since before the glaciers melted some 9,000 years ago. But their metaphorical resurrection may be the story outsiders need the most. Perhaps the visitors who pestered Cristina did so in desperate hopefulness that she would reveal what belonging means and how to become anchored in a world of mass movement. The visitors can go anywhere, but do they belong anywhere? And if you don’t belong anywhere, how can you possibly feel an obligation to place or to your neighbors, human and nonhuman?

To truly belong, the Yaghan remind us, is to know your place on this Earth. Their creation stories tell them, over and over, nothing is free on the land and sea, they have to work hard to live in balance with the sacred world around them, and their reward is not an afterlife, it’s the unquantifiable, almost infinite generations of life.

Jude Isabella writes about science and the environment for readers big and small. Her book, Salmon: A Scientific Memoir (2014), explores the human relationship with Pacific salmon, noting that the modern relationship is very one-sided. Jude’s latest book for kids, Bringing Back the Wolves, explores the ecological restoration of Yellowstone National Park in the United States. Photo by Grant Callegari

Video editor/producer Katrina Pyne came to Hakai Magazine from the East Coast of Canada with a background in visual storytelling and outdoor-centric journalism. She’s a fierce nature lover and has produced media content for a variety of publications from coast to coast. While she loves editing from her comfy office chair, she feels lucky that the camera affords her the opportunity to chase stories beyond her desk.

This article first appeared in Hakai Magazine, and is republished here with permission.