Ukraine, a major exporter of grains and other food crops, announced soon after the Russian invasion of the country that it would ban exports of many food crops to ensure that Ukraine has enough to feed its population.

Russia, another major exporter of grain, especially wheat, curtailed its exports of wheat, rye, barley, and corn. It also curtailed sugar exports.

The list of countries banning or reducing exports of foodstuffs is now increasing so quickly that it is starting to look like a pile-up on the freeway:

- Argentina, a major soy exporter, has halted exports of soy oil and soy meal.

- Hungary has banned grain exports.

- Moldova has halted exports of wheat, corn and sugar.

- India, the world’s second largest sugar producer, is contemplating capping sugar exports through the end of September. The 8-million-ton cap would effectively cut off sugar exports after May.

- Indonesia, the world’s largest exporter of palm oil, has curtailed exports to keep local prices in check as they have risen 50 percent so far this year.

- Serbia will stop exporting wheat, corn, flour and cooking oil.

- Turkey has halted the re-export of grains, oilseeds, cooking oil and other agricultural commodities sourced from other countries that are now sitting in warehouses and were bound for other countries until the ban.

- Jordan has banned export or re-export of rice, sugar, powder milk, dried legumes, fodders, wheat and wheat products, flour, yellow corn, ghee and all types of vegetable oil.

Of course, there are a wide range of natural resources, manufactured goods and other products that are no longer moving toward Russia because of sanctions resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. And there are counter-sanctions, most notably a ban on fertilizer exports from Russia which is the fourth largest producer of phosphate and nitrogen fertilizers in the world.

China, the world’s largest producer of phosphate fertilizer, banned exports last year through the end of 2022 to make sure China has enough for its own farmers. And China was hoarding grain long before the Russia/Ukraine conflict, stockpiling what is now thought to be half the world’s reserves of grain. In fact, the Chinese government went so far as to urge the Chinese public to stock up on food late last year with predictable and chaotic results.

Then there are threats to food crops unrelated to international conflict and actual levels of supply. A strike by Canadian National rail workers threatened to curtail shipments of Canadian fertilizer exports to the United States before the company made concessions that ended the strike.

Part of the reason for the sudden scramble for food and other resources is that since the early 1990s the watchword among industry, some governments and even some nonprofit service organizations has been “lean.” Running lean organizations—see a definition here—has been a way to improve profitability by reducing costs and streamlining processes to make organizations do more with less. Sounds perfectly sensible, doesn’t it?

Now, here’s the most important thing you need to know about “lean” organization principles: “Inventory is considered one of the biggest wastes in any production system.”

That explains a lot about how practically the entire world (except China) got caught caught flat-footed during the upset in logistical and food production systems in the face of a pandemic and now what is arguably the onset of World War III (although as I explained in a previous piece, this is not the world war we expected). Food, of course, isn’t the only thing that has been affected. Most notably, semiconductors found in a myriad of appliances, vehicles, electronic devices and industrial systems are in short supply as well.

But we do not need to eat semiconductors to live. Food is at the center of every society for obvious reasons. It is a credit to the lean-organization-free-trade-without-borders ideology that it lasted so long in the face of the obvious facts about the very nature of civilization. Let me end with an excerpt from a previous piece that makes the point:

Civilization, that is, the congregation of people in large settlements we call cities, is thought to owe its origins in part to the invention of agriculture. By growing surpluses of food crops farmers enabled the creation of an urban non-farming class who engaged in all manner of cultural, governmental, and commercial activities. These activities now preoccupy the vast majority of people in advanced economies.

From year to year the new settlements of ancient civilizations ensured their continuity through one very important measure: the storage of surplus food crops, especially grain. This enabled them to withstand a bad harvest or even two or three without facing collapse.

What a supreme irony then that the sine qua non of civilization–maintaining a store of essential materials–should in our time be considered a source of inefficiency and waste to be avoided at all costs.

I expect more countries and organizations to abandon the “lean” ideology and stock up in the coming months.

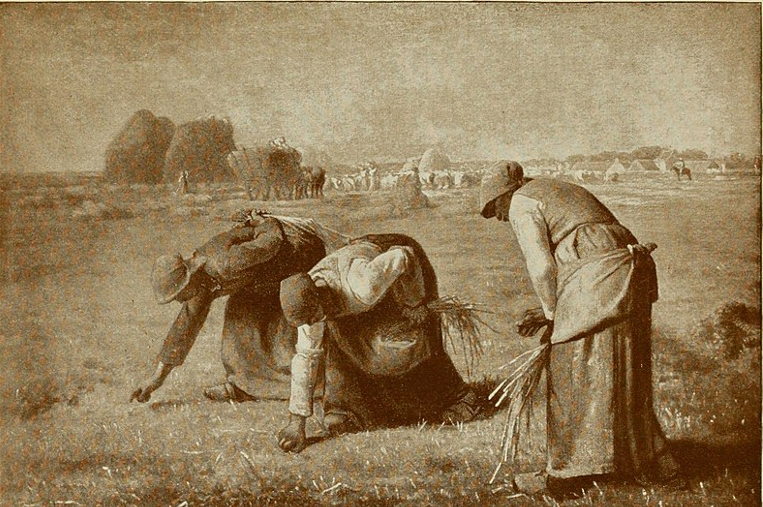

Image: “The Gleaners” by Millet (1857). “The gleaners are three women ofthe poorer peasant class. They are tidily dressed in their coarse working clothes, and wear kerchiefs tied over their heads, with the edge projecting a little over the forehead to shade the eyes. The dresses are cut rather low in the neck, for theirs is warm work. They make their way through the coarse stubble,as sharp as needles, gathering here and there a stray ear of the precious wheat. “

Via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean_Fran%C3%A7ois_Millet;_a_collection_of_fifteen_pictures_and_a_portrait_of_the_painter,_with_introduction_and_interpretation_(1900)_(14577650019).jpg