Part I: The Social Grammar of Destruction

Read the article in Italian

In this blog, I invite you to join me in a meditative journey on the current moment. We start with Putin’s war in Ukraine, unpack some of the deeper systemic forces at play, look at the emerging landscape of conflicting social fields, and conclude with what may well be the emerging superpower of 21st-century politics: our capacity to activate collective action from a shared awareness of the whole.

1. Crossing the Threshold

“The world will never be the same.” These are, according to New York Times columnist Tom Friedman, the seven most dangerous words in journalism. It’s not only Friedman who has used them to make sense of our current moment. Many of us are doing the same. Watching Putin’s invasion of Ukraine happen in real-time since February 24 makes most of us feel stuck and paralyzed by the horrific acts that are unfolding in front of us.

It feels as if we are crossing a threshold into a new period. This new period has been likened to the cold war era that ended in 1989. Some suggest that Vladimir Putin is trying to turn back the clock by at least 30 years in his effort to make Russia “great again.” I believe, though, that we are in a quite different situation today. The cold war was a conflict between two opposing social and economic systems on the basis of a shared military logic that experts refer to as mutually assured destruction — or MAD, a rather fitting acronym. The MAD “operating system” worked because it relied on a shared logic. It was grounded in a shared set of assumptions, and a shared sense of reality on both sides of the geopolitical divide.

Today, though, this shared logic and sense of reality has been fractured. We see it domestically in many countries, including, painfully, in the United States. Here we are seeing an erosion of the very basis of the democratic process as witnessed in the last elections. Since that election, we have one party who still is denying the legitimacy of the 2020 election results, while actively engaging in voter suppression (27 states have introduced more than 250 bills with restrictive voting provisions since Trump lost in 2020). Add to that the Facebook/Meta algorithm machine that supports the mass fabrication of outrage, anger, misinformation, and fear, and you see why this polarization and fragmentation amounts to an attack on the very foundations of democracy. The capacity of societies to hold spaces for making sense of complex social issues and analyze them from different perspectives is in most countries under attack and dissipating.

2. Putin’s Blind Spot

After Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014, Angela Merkel, the then Chancellor of Germany, talked to President Putin and reported to President Obama that, in her view, Mr. Putin had lost touch with reality. He was, she said, living in “another world.” This mindset of fragmentation, isolation, and separation is nowhere more strikingly visualized than in the recent pictures of Putin alone at one end of a massive table and his team (or occasionally a head of state), at the other end.

This isolation (from your team, from people who think differently, and eventually from reality), is obviously at odds with the increasingly volatile complexity of our real-world challenges today. Even though Putin, Commander-In-Chief of one of the most powerful armies in world history, may continue to win all the military battles for a while, it feels as if this separation from reality — that is, the reality of his own blind spots — have already sown the seeds of his demise. His blind spots seem to be the strength of civil society and the power of collective action from shared awareness.

The strength of civil society shows up in the courage and resolve of the Ukrainian people — not just the military personnel, but everyone. The whole population has dropped everything else in order to collaborate on their collective defense and survival in a way that touches and inspires just about everybody. Putin and the Russian army were evidently taken by surprise by this collective resolve. Their second surprise was the reaction in Russia. Civil society has shown up there too in the form of anti-war demonstrations in more than 1,000 cities across Russia; 7,000 Russian scientists signed an open letter against the war within a few days after the invasion started. These visible signals of dissent are not massive in size, yet. But they are an important beginning that could grow quickly into something much wider and deeper across Russia, even as Russian propaganda and suppression clamp down on any protest ever more harshly.

On the evening of February 24, the day the Russian army invaded Ukraine, the European Council, which comprises all 27 heads of state of EU countries, met in Brussels. When the meeting concluded, they announced a set of historic decisions and sanctions: sanctions targeting Russia’s financial, energy, and transportation sectors; a travel ban and asset freeze for key individuals and oligarchs; and direct military support for a non-EU country. On matters of foreign policy, the European Council must agree unanimously before taking action, and thus is notorious for often NOT acting. What had happened that created such historic and unanimous decisions? Why, on that evening and throughout the following week, were the EU members in such strong agreement?

We don’t yet know the full story, but there seem to be two significant enabling factors: (a) seeing the brutality of the Russian invasion and (b) a direct conversation between the EU leaders and President Zelensky from his bunker in Kyiv, in which he told his colleagues that it could well be the last time they see him alive. These events facilitated an awakening on the part of EU leaders: they realized that they are very much a part of the problem, that they were funding Putin’s war by buying Russian gas and oil, and that they needed to act very differently going forward.

This phenomenon, when a group of leaders begins to act from a shared seeing and a shared awareness of the whole situation — rather than from a multitude of abstract and narrowly defined national agendas — is what I refer to as Collective Action from Shared Awareness (CASA).

Why were Putin and his highly sophisticated intelligence team apparently unable to accurately assess and anticipate both the civil society response and the swift unity of the Western countries?

Nobody knows the answer to that question. But I have a hunch: because Putin’s intelligence system, which may be brilliant in analyzing existing formations and forces, has a blind spot when it comes to actions that arise from the heart and from a shared awareness of the whole. But that is precisely the kind of collective action that the brave Ukrainian people embody in such an inspiring way, and that is beginning to ripple out to the streets, villages, and cities in Russia and elsewhere, including rather unlikely places, such as the European Council in Brussels.

3. The Blind Spot of the West

Putin may have blind spots around the power of civil society, and the power of collective action that arises from shared awareness: but what about the blind spots of the West? Let me be more specific: IF it was that clear that Putin planned to invade Ukraine (as US intelligence had predicted for many months), and IF it was equally clear that NATO could never directly step in (without risking an all-out nuclear war), then WHY was it so impossible for the West to simply agree to Putin’s often repeated primary request: a guarantee that Ukraine would not be allowed to join NATO (just like Finland, Sweden, Austria, and Ireland, all of whom are members of the EU but not of NATO)?

What were Western — particularly US — leaders thinking? What was the rationality of the Western two-point strategy against Russia: (1) decades of ignoring and discounting Russian objections to the various waves of the eastward expansion of NATO, and (2) betting that Putin would change his behavior when threatened with economic sanctions?

That bet has always been a very long shot. The Soviet Union operated under these conditions for most of its existence. And today it simply strengthens the China-Russia alliance and economic integration. How is that a rational strategy if — as US President Biden sees it — China is viewed as the US’s primary strategic rival?

Ever since the first wave of NATO’s eastward expansion to the borders of the former Soviet Union, and then later inside these borders, a small number of considered voices in the US foreign policy establishment have warned that the expansion could lead to catastrophic consequences. In particular, George Kennan, the key architect of the Western cold war containment strategy against the Soviet Union, warned in a 1998 New York Times interview after the first round of NATO expansion, that he saw such a move as “the beginning of a new cold war.” He said, “I think the Russians will gradually react quite adversely and it will affect their policies. I think it is a tragic mistake. There was no reason for this whatsoever. No one was threatening anybody else.” Robert M. Gates, who served as Secretary of Defense in the administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama, reflected in his 2015 memoir that Bush’s initiative to bring Georgia and Ukraine into NATO was “truly overreaching.” In his view, it was “recklessly ignoring what the Russians considered their own vital national interests.”

Why was the Biden administration so deaf to the repeated Russian complaints? What would Americans say if, for instance, Mexico, were to join a hostile military alliance? What would happen if Mexico were joined by Texas (a state that formerly belonged to Mexico)? How would the White House feel if missiles in Houston were pointed at the US capital? Well, we can only guess. But we don’t have to guess in the case of Cuba. The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis instantly brought the world teetering toward World War III. What ended the crisis? The Russians pulled their medium-range missiles out of Cuba. That’s what everyone remembers. What no one remembers is the second part of the agreement with the Russians: the US pulled its own medium-range missiles out of Turkey. That part of the deal was kept secret so President Kennedy would not come across as weak to the US public.

This brings us right back to Biden. Why is US foreign policy perpetually unable to respect the security concerns of another major nuclear power that has been invaded by Western forces more than once (Hitler, Napoleon) and that in the 1990s went through another traumatic experience: the collapse of both its empire and its economy (guided by the advice of Western experts)?

What made the simple acknowledgment of these concerns so difficult? Was it ignorance? Arrogance? Or simply an inability to build real relationships with a perhaps traumatized president of a country that lost 24 million people during World War II? Whatever the reason, the fact is that THAT strategy — whatever it may have been — crashed and burned.

Pointing out these shortcomings in America today is just as popular as it was in 2003 to criticize the US invasion of Iraq (which, like the invasion of Ukraine, was conducted on false and fabricated pretenses). No one wants to hear it. Because it’s part of the collective Western blind spot: our own role in the making of the tragedy that is unfolding in Ukraine.

It is worth noting that George W. Bush, after launching the war on terror in 2001, at the end of his second term decided to make another major move: inviting Ukraine (and Georgia) into NATO. That decision seeded another chain of potentially catastrophic events that, 14 years later, in 2022, is exploding in our face.

Both of these Bush blunders resulted from the same intellectual structure: binary thinking that is based on dividing the world into good and evil. It’s that paradigm of thought that prevented policymakers from conceiving of a 9/11 response other than a war on terror or a role for Ukraine other than that of a state facing a hostile (and increasingly isolated) Russia. Why not see Ukraine as a flourishing bridge that links the EU with Russia, with both EU membership and deep ties to Russia, but without membership in any military alliance (like Finland, Sweden, Austria, and Ireland)?

4. The Social Grammar of Destruction: Absencing

If we step back a bit to look at the deeper cognitive structure that is giving rise to this war, what do we see?

We see a system that leads us to collectively create results that nobody wants. I do not believe that anyone in the world wanted to see what we now see in Ukraine. Definitely not the Ukrainians. And certainly not the Russian kids/soldiers who have been “duped” into war, as several of them have described it. Perhaps not even Vladimir Putin. He probably thought it would be as easy as his Crimean invasion in 2014. So why are we collectively creating results that nobody wants — that is, a dirty war, even more environmental destruction, and a brutalization and traumatization of our souls?

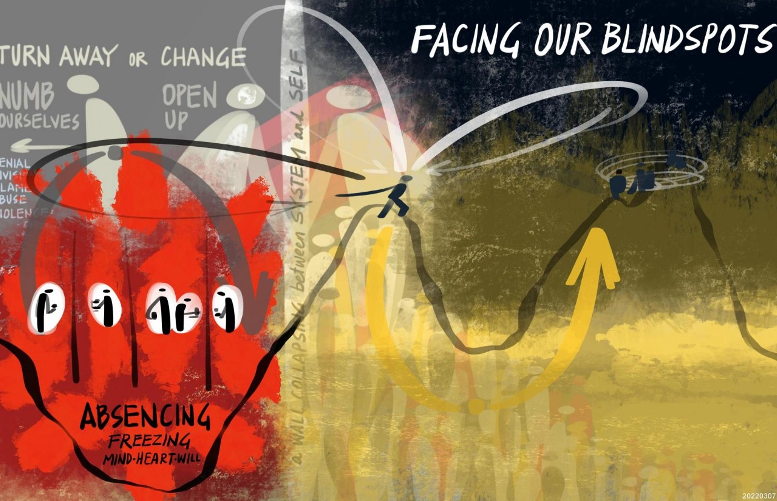

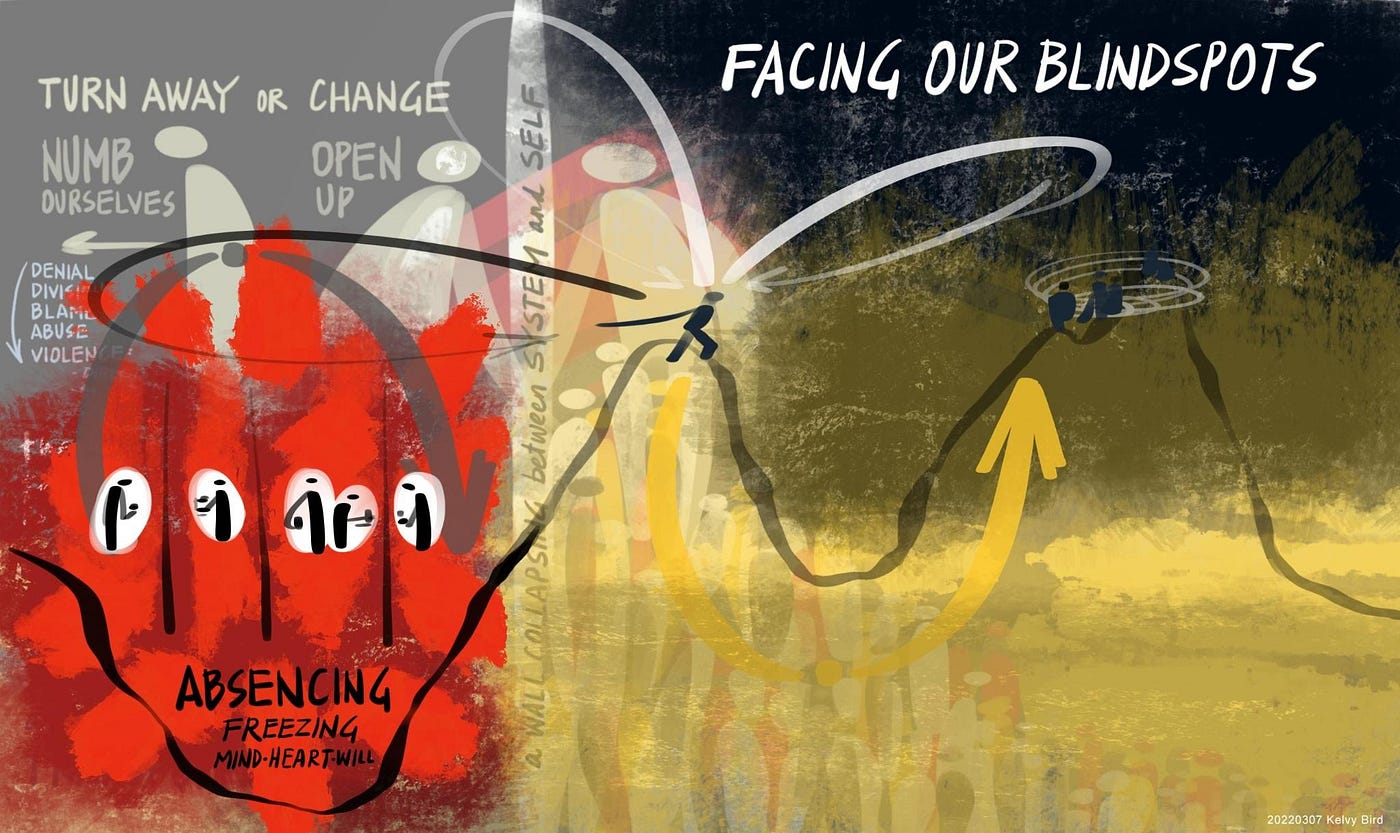

Figure 1: Creation and Destruction: Two Social Grammars and Two Social Fields

Figure 1 distinguishes between two interior conditions that we as human beings can choose to operate from. One is based on opening the mind, heart, and will — a.k.a. curiosity, compassion, and courage — and the other one is based on closing the mind, heart, and will — ignorance, hate, and fear.

The upper half of figure 1 briefly summarizes the collective cognitive dynamics that have led us to Putin’s war in Ukraine. The freezing and closing of the mind, heart, and will have resulted in six debilitating social and cognitive practices:

· Deceiving: not telling the truth (disinformation and lies).

· De-sensing: not feeling others (stuck inside one’s own echo chamber).

· Absencing: disconnecting from purpose (depression, a disconnect from one’s highest future).

· Blaming others: an inability to recognize one’s own role through the eyes of others.

· Violence: direct, structural, and attentional violence.

· Destruction: of planet, of people, of Self

These six micro cognitive practices represent an operating system that manifests with many faces, one of which could be called Putinism. What are some of the other faces that we see, where the same cognitive operating system is at work? Trumpism of course is a major one, as I have discussed on earlier occasions. In spite of some obvious differences, Trumpism and Putinism share the same six cognitive core components that define their respective ways of operating. A particularly heart-wrenching example of the impact of Putinism on his own troops came in a text message sent by a young Russian soldier to his mother, right before he died:

“Mama, I’m in Ukraine. There is a real war raging here. I’m afraid. We are bombing all of the cities together, even targeting civilians. We were told that they would welcome us, and they are falling under our armored vehicles, throwing themselves under the wheels, and not allowing us to pass. They call us fascists. Mama, this is so hard.”

This reported text message tells us about deceit (“we were told…”), de-sensing (“they are falling under our armored vehicles…”), and destruction (“we are bombing all of the cities…even targeting civilians”). His final words “Mama, this is so hard” put language to the awakening of an awareness that this path he found himself on — the path of destruction — was profoundly wrong.

The social grammar of destruction is shaping collective behavior on many societal levels today. Consider the climate-denial industry. In the early 2000s, the oil and gas industry in the United States noticed that the majority of the public, including the majority of Republican voters, supported the introduction of a carbon tax to better address global warming and climate destabilization. They launched a campaign that was well organized and well-funded (with more than $500 million), and effectively put the climate-denial industry on the map. One key strategy was to discredit climate science and climate scientists by sowing and amplifying voices of doubt. It worked. The campaign succeeded in turning public opinion in the US around. The intervention focused on the early part of the absencing cycle (deceiving by sowing disinformation and doubt), while the impact disproportionately hits the most vulnerable, both now and in the future (through the destruction caused by climate destabilization).

Another example is Big Tech. The problem with most social media giants is not that they don’t shut down sites that amplify disinformation. The problem is the entire business model that made Facebook a trillion-dollar company. It is a business model based on maximizing user engagement by activating and amplifying disinformation, anger, hate, and fear. Facebook, like Trumpism and Putinism, activates the same cognitive and social behaviors as I have discussed in other places: deceit (disinformation gets more shares than real information), de-sensing (echo chambers, anger, hate), absencing (amplification of depression), blaming (trolling), destruction (violence against refugees proportional to Facebook use), all of which eventually leads us toward self-destruction.

Last example: 9/11. Like all acts of terrorism, the attacks of 9/11 embody 100% of the grammar of destruction (the recruitment and training of suicide bombers also follow these patterns). When that attack happened, America had a choice: it could choose to respond by opening or by closing the mind, heart, and will. We all know what happened. It was the freeze reaction of the mind, heart, and will that took precedence and resulted in launching the “war on terror.” Fast forward 20 years. What resulted from that choice? Five major outcomes:

· It cost $8 trillion and 900,000 lives, and it left the Taliban and Al Qaeda much stronger than they were 20 years ago.

· It led the US to torture innocent people, thereby violating the very values that the war claimed to defend.

· It resulted in a comprehensive domestic surveillance system that was unthinkable before.

· It sowed a general mistrust in institutions that eventually gave rise to domestic terrorism in the US, including the attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021.

· Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it prompted us to lose sight of the real global challenge of our time: the planetary and social emergencies that need new forms of global collaboration for decisive collective action now.

Clearly, the phenomenon that is Putinism is not entirely new. It’s manifesting on the geopolitical stage something that we have seen before in smaller contexts. We see it in Trumpism. We see it in our own collective behavior towards climate change. We see it in the appalling treatment of Africans at the Ukrainian-Polish border. We see it in the unequal attention by Western media to the war in Ukraine compared to those in Sudan, Syria, or Myanmar. We see it whenever we lose our way and collectively enact results that inflict violence on others, be that direct, structural, or attentional violence. None of that is new. What is new is the growth of this phenomenon over the past decade or two, which is at least in part related to the amplification of toxic social fields through social media and Big Tech.

So, what do we see when we look at reality through the lens of the two social fields, or the two social grammars, that I described above? We see that one of these fields has grown exponentially while the other one seems to have been crowded out. This is of course why so many of us are living with increasing anxiety, depression, and despair. That’s the story of what I call “absencing.” In the second part of this essay, I will tell a completely different story, one that looks at the current events through a different lens: the lens of “presencing” — that is, the future that is beginning to emerge through awareness-based collective actions now.

Part II: The Social Grammar of Creation: coming soon

Thanks to my colleagues Kelvy Bird for the visual at the opening of this reflection and to Becky Buell, Eva Pomeroy, Maria Daniel Bras, Priya Mahtani, and Rachel Hentsch for their helpful comments and edits on the draft. For other blog posts check out: homepage