Combating the climate crisis requires the restructuring of the economic and energy system including, first and foremost, the phaseout of coal, which is the highest-emitting energy source.

The changes that go hand-in-hand with this restructuring do not happen in a vacuum, but instead interact with existing power asymmetries in societies.

This means that they affect different social groups, such as men and women, in different ways.

In the discourse around the coal phaseout and the policies accompanying it, the focus is on the predominantly male miners employed in the industry, while the impact on women and their role in the transition remains mostly invisible.

Our research has revealed how, during historical coal transitions, women were affected differently and became politically active in different ways than men.

A just transition away from fossil fuels will not be possible unless these differences are taken into account, when designing policies to mitigate the impact of this shift.

Coal and gender

Science should be able to examine different starting conditions, needs and interests and help to create a basis for equitable policy measures, but so far this scientific basis hardly exists for energy transitions.

Scholars often only analyse the broader economic impacts of such structural changes, such as net-employment effects for entire regions.

Meanwhile, the impact on distinct groups and their differing opportunities to participate in decision-making processes remains under-researched. If there is a focus on one group, it is on the largely male employees in the coal industry.

This focus on mitigating the negative effects on men, while ignoring the negative effects on women, can lead to the reproduction of existing inequalities between men and women.

With policy measures adapted to people’s differentiated needs, energy transitions could instead be an opportunity to overcome existing unjust power relations.

In a study published in the journal Energies last year, we conducted a systematic literature review on the topic of coal transitions and gender.

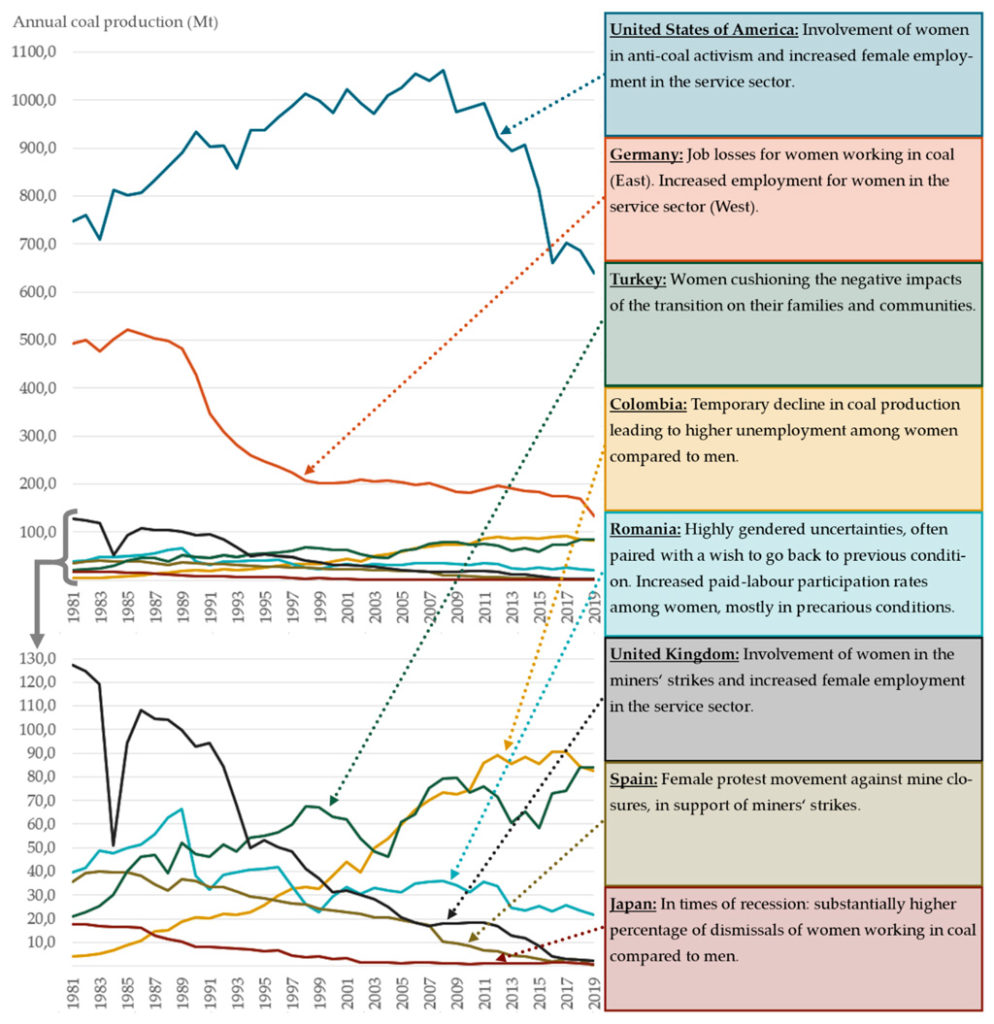

The figure below shows the extent of coal production decline in the countries assessed, and the most important aspects relating to coal transitions and gender in those countries, ranging from Colombia to Germany.

Overview of annual coal production (charts on left, million tonnes – Mt) between 1981 and 2019 across a selection of nations, with annotations indicating notable events in their coal transitions that relate to gender. These examples were identified in a literature review of gender and coal transitions. Source: Walk et al. (2021).

Coal transitions in the UK and the US

Most of the existing literature on this topic refers to the transition in the UK and the US. Therefore, our second paper, published in Energy Research & Social Science, focuses primarily on these two nations.

Both are major historical coal centres, although the UK’s production has now almost completely stopped while the US continues to produce large volumes.

In the UK, the literature mainly addresses the decline in coal production between the 1920s and the 1940s, and in the 1980s. US literature focuses on the Appalachian coal region, mainly covering the time period from 1990 to the early 2000s.

Across both transitions away from coal, there were many parallels in terms of the effects on women.

During the transition, there was an increase in women taking up wage employment in both countries, especially in the service sector. This employment was mostly poorly paid and precarious, but it gave women some financial independence.

Despite this trend, women were still mainly responsible for care work, which increased their overall workload.

In former coal regions, the coal exit sometimes led to an identity crisis for people in these regions. Some publications report that it was mainly women who did a lot of emotional work to alleviate these crises, maintained social networks and compensated for the loss of social institutions, such as youth clubs formerly funded by the coal industry.

The loss of jobs and identities for former coal miners and the new roles of women as wage earners also led to conflicts within families.

Pro-coal and anti-coal movements

The role of women in the political process around the coal phaseout has been very different in the two cases study countries.

The literature on the UK focuses primarily on the role of women in the miners’ strikes in the 1920s, 1940s and 1980s, which they wanted to support in an effort to save as many coal mines as possible from closure.

However, this was difficult for women as they were largely denied access to important organisations, especially trade unions. In response, they founded their own organisations, such as National Women Against Pit Closure, which was set up nationwide and received a lot of media publicity.

By contrast, the literature on Appalachia focuses on the role of women in anti-coal protests, which increased significantly in the 1990s and 2000s as the environmentally damaging mining method of mountaintop removal became more widespread.

Women mostly led these movements. They were driven by a desire to protect their land, whereas men tended to shy away from the protests because they were more emotionally attached to the coal industry.

Gender-just transition policies

Based on this research, we have derived a series of policy options to help make structural change processes in coal transitions more gender-equitable. For example:

- Working conditions in sectors where mainly women work (care, service sector, etc.) could be improved generally, but especially during fossil fuel phaseouts as the development of the service sector can be an important economic pillar for the region.

- Retraining and professional development opportunities could address women in regions affected by structural change, rather than only being accessible to and tailored for men employed in the fossil-fuel industry.

- Giving stronger value to the caring and emotional work in the context of structural change processes and continued financing for social and cultural institutions.

- Provision of self-help groups or other forms of psychological support for ex-miners, who are mainly men, to cope with the loss of a very identity-forming job.

- Ensuring the comprehensive and needs-based provision of nursing and care facilities to remove some of the burden from women and enable them to participate in the structural changes that are taking place.

- Institutionalisation of women’s interests, for example by ensuring an equal representation of women in decision-making processes, such as expert groups and local politics.

- Provision of special funding to grassroots organisations and community based work, as these are forms of organisations especially used by women.

- Support for organisations in which women come together to represent their interests.

The nexus between gender and coal transitions remains largely under-researched and there is a great need for much more gender-aggregated qualitative and quantitative data.

Understanding women’s needs and positions more thoroughly is key to ensuring a just transition for everybody.

Walk, P. et al. (2021), Strengthening gender justice in a just transition: A research agenda based on a systematic map of gender in coal transitions, Energies, doi: 10.3390/en14185985

Braunger, I. & Walk, P. (2022), Power in transitions: Gendered power asymmetries in the United Kingdom and the United States coal transitions, Energy Research & Social Science, doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102474

Teaser photo credit: By Nick from Bristol, UK – Miners' Strike rally, 1984, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7256753