There is a scene depicting a Great Depression bank run in the famous holiday movie, “It’s a Wonderful Life.” In this scene, Jimmy Stewart’s character, George Bailey, is sidetracked from his honeymoon by hordes of people rushing the doors of the community savings and loan bank he manages.

The shareholders have all come to withdraw their savings in a bank run. Bailey jumps over the counter and addresses them with a speech crystallizing the conflict between large-scale market forces and bottom-up community development.

Bailey explains to his terrified customers the cash to cover their account balances isn’t sitting in piles in the safe. The money is in their community. They’ve loaned each other money to build homes, so they don’t have to live in the slums owned by the cold-hearted real estate baron, Mr. Potter.

Meanwhile, Potter’s private bank down the street is offering George Bailey’s members fifty cents on the dollar for their shares in the community bank. “Better to get half of my money now than none,” one customer says, as they move for the door to take Potter’s offer.

“You’re looking at this all wrong,” Bailey tells them as he blocks the exit to the door. “ Potter’s not selling, he’s buying! … We’re panicking and he’s not.”

Shift through 80 years of time and space to the Hunts Point neighborhood in the South Bronx—an oft-forgotten, industrial corner of New York City. In the South Bronx, hundreds (or thousands) of Mr. Potters preside over a complex of large affordable housing developments, dollar stores, check cashing businesses, fast food restaurants, and liquor stores.

It was once home to a thriving light-industrial and residential area with piano factories, an ironworks, and multi-generation immigrant families building homes across the Bronx River from Manhattan. When Robert Moses’ Suburban Experiment cut it up with interstate highways to move Manhattan workers out to the developing suburbs, Hunts Point and the South Bronx neighborhood got the exhaust, the waste incinerators, the toxic dump sites, and the industrial activities nobody else wanted.

George Bailey and his small town savings and loan are nowhere to be found in Hunts Point, but there you will find Majora Carter. The Bronx-born community advocate is not talking customers into holding onto their investments in a savings and loan bank run. But similar to Bailey, she’s exhorting her community not to panic, not to sell. She advises them to stay put, hold on, invest their time, love their children, keep their homes, and build their businesses. But above all, says Carter, remember this:

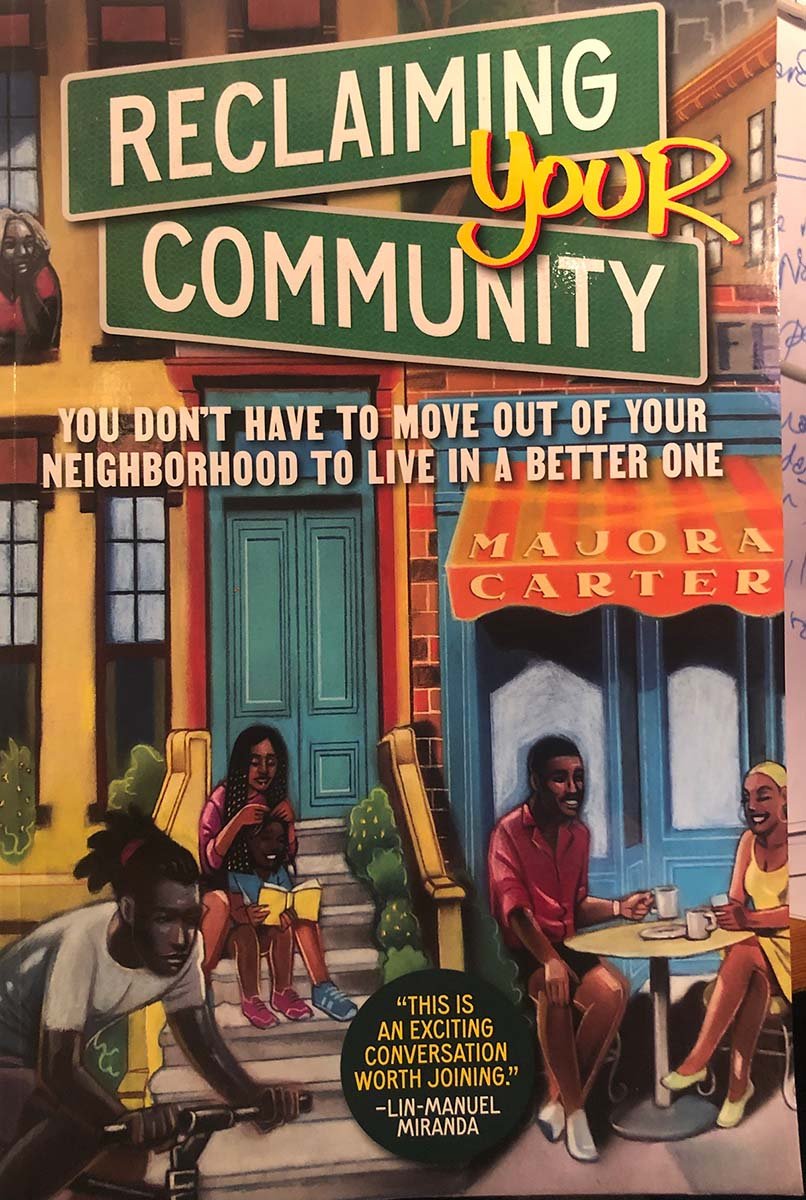

“You don’t have to move out of your neighborhood to live in a better one.”

(Source: Author.)

That’s the subtitle of Reclaiming Your Community, Carter’s book to be released February 1. In the book, the MacArthur Foundation “genius” award winner—often framed by others’ words in media accounts—tells her own story. It covers a lot of ground; from a shy and academically oriented child in the 1970s, through the burning of the Bronx and the birth of hip hop, to her emergence as a (sometimes) controversial community leader, and ultimately a developer and consultant.

A central decision in Carter’s story is her choice to go back home to the Bronx after college. Unlike most of her neighborhood peers, Carter made it to college and graduate school. She could have chosen a one-way ticket out of her blighted neighborhood, forever, since she learned to consider herself and her community to be defective and broken, she writes. Like most

“hometown heroes…[w]e are taught to measure success by how far we get away from our own communities.”

Instead, she came home and stayed with her family to save money during graduate school and ended up beginning a career doing community development in her own neighborhood. She founded Sustainable South Bronx, created a park out of a dump on the Bronx River, started job training organizations for young residents of her neighborhood, built a coffee shop, and other initiatives.

Many of those projects failed, lacking the support of city leaders, real estate investors, and the “non-profit industrial complex.” But she developed a massive media profile and became a sought-after speaker and consultant.

Tucked in among her larger successes and failures was Carter’s first ongoing development project, essentially squatting and taking adverse possession of a house across the street from her family home. The house had been owned by an elderly neighbor who passed away and left the house with no active manager, other than Carter’s family. She lives in the townhome to this day and plans to hold onto it.

Carter’s investment in her community and in developing her personal home across the street from her family home is part of her identity, but is also a wealth-building mechanism, the most common successful method in North America. She wants it for her community: something she calls “self-gentrifying in the South Bronx.”

When her family sold their home after her parents died, a $15,000 investment made by her father in the 1940s was worth $300,000. If they still owned it today, its market value would be more like $700,000. Carter says it is imperative families in low-status neighborhoods like Hunts Point see the value of their communities, instead of leaving that value for investors outside the community to exploit.

“[M]any folks are selling because they have been led to believe that there is no value in their communities,” Carter writes. “They often sell early and cheap and thus do not participate in the gains that happen in their former communities.”

Majora Carter. (Source: Wikimedia Commons.)

Strong Towns has written about how difficult it is for blighted or low-status communities to begin a path of bottom-up development. One possible solution is being tested at a land bank in Hartford, which is training residents of the North End to become developers for foreclosed, boarded-up properties in their neighborhood.

It takes more than affordable capital from the banking industry to get community-led development rolling, it takes human infrastructure, as well, as Dr. Adonia Lugo has written about widely—and discussed with Strong Towns. There are many assets in every community and organizing the people who will identify and harness them is a human infrastructure project, as is developing an inventory of community assets as Strong Towns Community Builder John Pattison wrote about this week.

“Gentrification doesn’t start when you see middle-class White people, cute cafés, and doggie daycares in formerly poor communities of color, or even when predatory speculators smell the blood of an easy victim,” Carter writes. “It starts when people in low-status communities believe there is no value there. On economic, spiritual and emotional levels, it is not uncommon for many of us born and raised in low-status communities to disengage from them instead of building them up.”

The profit margins are huge, Carter claims, for politically well-connected developers who build status-quo, low-income housing projects. Such projects, she argues, perpetuate generational poverty. They “cater to people stuck in the cycle of poverty within low-status communities” with “food banks and rental housing assistance, versus programs designed to improve their economic well being, such as financial literacy, credit repair, homeowner stabilization, and local entrepreneurial development.”

Carter wants to “broaden the idea of who should do development and expand an approach that creates reasons for emotional and economic wealth creation in low-status communities and is designed to retain talent, not repel it.” She argues that low-status communities are “places where inequality is assumed—both inside and outside those communities. They are inner cities, reservations, former Rust Belt towns with lots of White folks whose manufacturing jobs are long gone.”

Carter’s bottom-up, incremental approach could be used to develop such small communities away from urban centers, towns in serious trouble. Many small towns have become increasingly fragile as they try to maintain economic vitality while supporting and maintaining large capital infrastructure projects.

Tens of millions of people left rural communities in the second half of the twentieth century, and many communities continue to lose their young people to larger cities. Rural taxpayers subsidize their own demise, even as they pursue an approach to growth that is designed to decline.

Like the character of George Bailey and the recommendations of Strong Towns proponents, Carter advocates for her neighbors to take the bottom-up approach to creating public investments. Only then can incremental changes take hold to increase the value and resilience of a community.