For Edna Ibarra, it was the realization that with every breath her 11-year-old son was breathing in a little more of an industrial carcinogen that drove her to get involved in the fight against air pollution in Laredo, Texas.

And her son isn’t the only child exposed to this risk. Close to Ibarra’s home in the La Bota neighborhood of Laredo, you’ll find the Julia Bird Jones Muller Elementary School, a public school attended by roughly 880 kids from kindergarten to 5th grade, almost all of whom are Hispanic. And about 1.6 miles away is a plant owned by Midwest Sterilization Corp — one of the nation’s largest emitters of the carcinogenic chemical, ethylene oxide (EtO).

“How do you say, okay, let them breathe something that I know, that EPA knows, that everyone knows causes cancer?” Ibarra, now a member of the Clean Air Laredo Coalition, asked at a December 8 community meeting held in Lardeo’s Fasken Recreation Center. “He’s been breathing EtO for 11 years. You tell me that’s right. Would you want that for your kids?”

The community meeting, attended in person by over 100 people and virtually by another 50, focused on the risks that EtO poses for Laredo, a border town on the banks of the Rio Grande that more than a quarter of a million people call home. It’s only been in the past five years that federal regulators have recognized how carcinogenic EtO is, particularly the risks it poses for children.

Concerned citizens at meeting listening to alarming information about ethylene oxide in their air. Credit: Julie Dermansky

There was standing room only at the December 8 community meeting in Laredo, Texas. Credit: Julie Dermansky

Speakers including council members, members of the Clean Air Coalition, and members of two other communities exposed to EtO shared information about the chemical, and what the process to limit the communities exposure entails. While some community members said they had expected that once the government identifies a risk to the public it would act quickly to protect them, too often that isn’t how it works when it comes to chemical exposure.

In many ways, EtO is a poster child for the ways that industry and regulators have, for decades, failed to effectively protect people from chemical safety hazards and health threats like cancer. The Laredo meeting reflects a growing backlash against the petrochemical industry amid rising awareness of the sector’s deadly risks, particularly for communities of color, as well as its climate-altering impacts.

EtO is a colorless flammable gas that’s used to make plastics, anti-freeze, and adhesives, and also to sterilize medical equipment. In addition to cancers including non-Hodgkin lymphoma, breast cancer, and leukemia, the chemical has also been linked to reproductive problems, breathing issues, and memory loss. A volatile organic compound (VOC), it was included as one of the 188 hazardous air pollutants recognized in the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments, alongside notorious carcinogens like asbestos and benzene.

Even after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recognized in 2016 that the chemical was a potent carcinogen, it failed to communicate those risks to people who lived near sites that pump EtO into the air, the agency’s own internal watchdog found.

In December 2016, following an assessment by the EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System, the EPA concluded that EtO turned out to be 30 times more powerful as a carcinogen for adults than previously thought. For children, the EPA added, EtO proved to be 60 times more carcinogenic than previously believed.

In fact, it’s now believed to be so carcinogenic that a 2019 investigation by the Intercept concluded that EtO and two other air pollutants, chloroprene and formaldehyde, are “responsible for more than 90 percent of the cancer risk from air pollution in the 109 census tracts that have an officially elevated risk” of cancer nationwide, according to the EPA. “If these three pollutants were eliminated,” the Intercept reported, “only one census tract in the U.S. would have a cancer risk from air pollution above 100 per million.”

In 2019, the EPA revised its recommendations on EtO — but those recommendations haven’t been adopted in many states, including Texas. The EPA is currently working on drafting new binding rules and regulations on EtO, with the first expected next year.

Pollution Impacting Schools

For over 30 years, Midwest Sterilization Corp. has used EtO to sterilize medical devices like kits used during surgeries. The company began operating in Laredo, Texas, in 2005, EPA data shows, and in the 15 years since has reported releasing roughly 200,000 pounds of ethylene oxide, a gas whose faintly sweet scent has been described as “reminiscent of bruised apples,” into the air.

Midwest Sterilization facility in Laredo, Texas. Credit: Julie Dermansky

And virtually all of the air pollution reportedly affecting Muller Elementary is ethylene oxide from Midwest Sterilization Corp., according to a University of Massachusetts at Amherst air toxics database published this year.

Muller ranks in the top 25 schools where students’ long-term health is most at risk from toxic air pollution in the U.S., the database shows, and Muller’s toxic air pollution impacts are over 205 times the national average.

And Muller Elementary isn’t alone. Ten of Laredo’s schools rank in the nation’s top 1 percent of schools where students are most at risk from toxic air pollution, in large part due to ethylene oxide pollution.

“This cancer-causing gas being emitted into Laredo’s air by Midwest must come to an end now,” attorney Daniel Elizondo, a co-founder of Clean Air Laredo Coalition said in a statement about the community meeting. “Laredoans deserve and must demand that their air is clean and free of ethylene oxide.”

Daniel Elizondo, co-founder of Clean Air Laredo Coalition, speaking at the community meeting. Credit: Julie Dermansky

Across Laredo, the cancer risk is at least 75 percent higher than the U.S. average, the Laredo Morning Times reported this month, adding that 94 of Laredo’s 95 schools rank within the country’s top 6 percent of schools in cancer risk.

In March 2020, a report by the EPA’s inspector general, its internal watchdog, found that the EPA had failed to inform over two dozen communities exposed to EtO, including Laredo, about the cancer risks the chemical poses. EPA’s Region 6, which covers Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, and 66 Tribal Nations, had taken no action at all to directly inform residents living near EtO emitters, the report found.

About half of the 25 “high priority” EtO sites identified in that report were sterilizers and half were chemical plants, including, for example, the Air Products Performance Manufacturing chemical plant in Reserve, Louisiana — part of a Gulf Coast region packed with refineries and chemical plants that’s become known internationally as “Cancer Alley.”

Environmental Justice Communities Bear the Brunt

The chemical industry’s air pollution — and the ways that it too often affects people in racially and economically discriminatory patterns — has drawn increasing scrutiny over the past several years as the shale rush and fracking have propelled a building spree for petrochemical projects.

A report published last week highlighted the role that chemical plants play in driving climate change. The report, “The Chemical Industry: An Overlooked Driver of the Climate Crisis,” was published by Coming Clean, a national environmental health and justice network, and concluded that roughly 7 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the chemical sector — and that percentage is predicted to grow as the energy transition pushes other sectors away from fossil fuels and towards lower-cost and less polluting renewable energy sources.

Community members in Laredo, Texas, standing along the wall of a full room in the Fasken Recreation Center on Dec. 8, 2021, during the ethylene oxide town hall meeting about local air quality concerns. Credit: Julie Dermansky

A companion report by the same organization, “Addressing Environmental Injustice Through the Adoption of Cumulative Impacts Policies,” highlighted the ways that communities of color are more likely to bear the brunt of toxic air pollution. A collection of over 100 organizations cited the reports’ findings in calling for a revamped approach to chemical industry regulation following the recommendations of the Louisville Charter for Safer Chemicals, released in 2004 and updated this year.

Roughly half of the nation’s top EtO polluters are found in communities “where more than half the population living within a 3-mile radius” are people of color, a June 2019 letter from Senators Tom Carper, Tammy Duckworth, and Cory A. Booker to the EPA noted.

An investigation earlier that year by the Intercept described the ways that Willowbrook, Illinois, a largely white suburb with a median income of $92,000, was able to organize and force an end to EtO emissions from a sterilization plant in their town, adding that meanwhile, the

“EPA has paid far less attention to the eight less affluent, less white communities in Louisiana, Pennsylvania, Colorado, Texas, Puerto Rico, and West Virginia where the risk of cancer from ethylene oxide is even greater.”

Today, Illinois, which since 2019 has set some of the nation’s strictest restrictions on EtO, is considering a bill that would require regulators to conduct fence-line monitoring tests for EtO if plants are in densely populated areas.

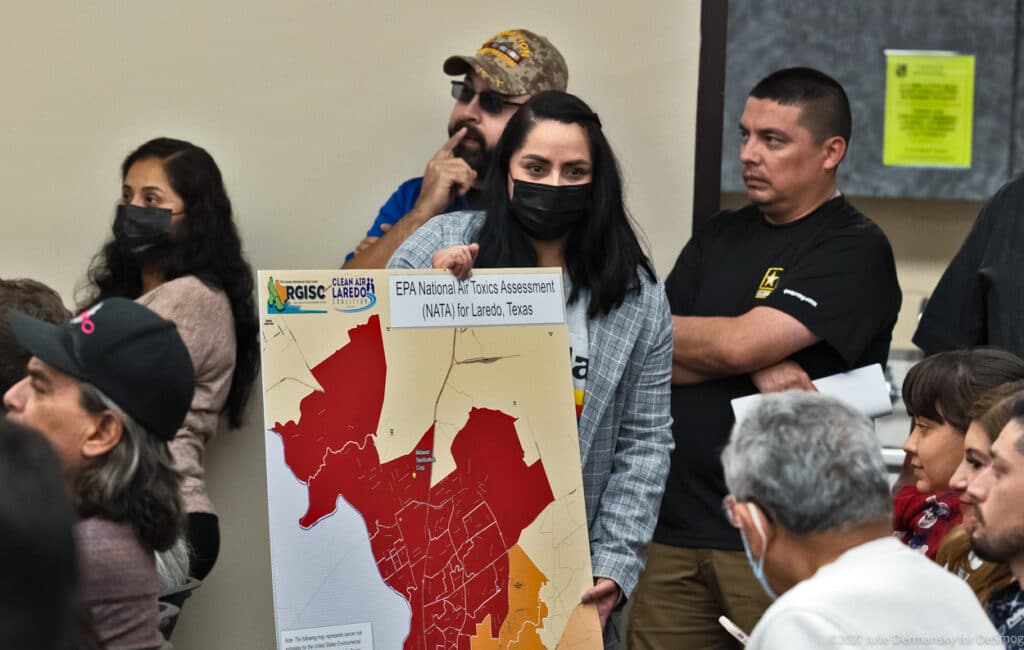

Marilyn Bautista, a Rio Grande International Study Center member, carrying around a map of the EPA National Air Toxins Assessment to a room full of concerned citizens, during the ethylene oxide town hall meeting at the Fasken Recreation Center on December 8, 2021. Credit: Julie Dermansky

Organizers at the Laredo community meeting called for similar monitoring in their neighborhoods.

“We can install air monitoring on the fence line of Midwest, throughout the city of Laredo, and especially at the schools that are in the top one percent in being the most toxic in the entire United States,” Elizondo said.

Elizondo and other speakers also noted that Laredo is a community that is underserved when it comes access to medical care:

“We have to also take into consideration that the data we may have, may be skewed because some people who may end up being diagnosed with cancer may be crossing [the border] to get their medical treatment.”

The council members at the meeting supported the idea of rapidly setting up air monitoring, as did the health officials, who also want to do bloodwork on at least 3,000 people to better understand the extent to which people’s health is actually being affected by EtO emissions.

“We have to understand the concept of correlation and causation,” said Dr. Victor Trevino of the Laredo Health Authority and part of the Clean Air Coalition. “We need all the information that we can get.”

Calls for Stronger Action

Community members asked if there was anything they could do to protect themselves and their children, from wearing masks to homeschooling their kids. With EtO, presenters responded, kids won’t be safer at home than at school. And the chemical can pass through protective equipment like N-95 masks, unlike many other air pollutants — in fact, it’s prized for its ability to pass through packaging as it sanitizes. That makes it harder for individuals to protect themselves. Presenters also said that EtO would go away quickly if the emissions were to stop; it isn’t a chemical that lingers.

Community meeting was at full capacity. Credit: Julie Dermansky

Following the meeting, Midwest Sterilization put out a statement on EtO. “The health and safety of our employees and community residents is our highest priority,” the statement said, KGNS TV reported. “We remain strongly committed to improving patient health and safeguarding lives. This includes ensuring that the public health and safety precautions extend not only to our employees, but to the engineers and scientists who help design and manufacture medical devices, and to neighbors and families in the communities where we live and work.”

The statement also notes that Midwest is in compliance with the standards required by the EPA and by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) and that their emissions remain below the 12,000 pounds a year allowed by their air permits.

The TCEQ’s standards on EtO, however, remain far less stringent than the EPA’s current recommendations, with the Intercept reporting that the Texas standard for EtO is “about 2,000 times less protective than that of the EPA [and] was calculated at least in part by the companies that profit from the ability to emit ethylene oxide.”

The Texas standards were set before the EPA determined EtO was officially a carcinogen and TCEQ later raised objections to the EPA’s analysis, with one TCEQ toxicologist arguing the EPA should have used a different methodology in its 2016 report.

Community members at the meeting in Laredo said they had trouble comprehending how public officials could have left them exposed to dangerous and deadly chemicals for so many years. Councilman Dr. Marte Martinez did his best to explain the complicated dance between the different state, federal, and local regulations, but the simple answer when he was asked if the city could do anything immediately was “no.”

Tricia Cortez of the Rio Grande International Study Center speaking at the community meeting. Credit: Julie Dermansky

TCEQ has previously pointed out that the company is operating within its emission limits allowed by its permits and that cancer rates in the area closest to the plant don’t reflect increases of cancers associated with EtO. But attendees at the meeting noted that there are numerous reasons reported rates of cancer are not an accurate way to determine how dangerous a chemical is — which is why the EPA’s data deals with cancer risk, not cancer rates.

But none of the presenters at the community meeting were persuaded that the air permits in Laredo were sufficiently protective.

“Just because they are abiding by their permit and so it’s not illegal, it doesn’t make the poisoning of our air any safer or okay,” said Tricia Cortez of the Rio Grande International Study Center, also a member of the Clean Air Coalition.

“We don’t want to be a sacrifice zone for one company to sterilize products for the rest of the country,” she added, “and we are left to bear the burden.”

Maria G. Salazar, with tears in her eyes after talking about the death of her son to cancer. Credit: Julie Dermansky

Toward the end of the community meeting, Maria G. Salazar spoke through her tears about the death of her older son from cancer in 2019. She said that his doctors couldn’t explain why he got it, but suggested the cause was environmental. She offered to make her son’s medical records public if that might help the city solve this problem.

“I want to help so other parents don’t have to go through what I went through,” she said. She also wanted the community to know that it wasn’t just her child who had cancer — she knows of 10 others at the same school. Many in the room had tears rolling down their cheeks by the time she finished speaking.

Other parents at the meeting expressed outrage and fear over EtO’s threat, particularly for children attending schools where EtO levels are high, and worry for the health of the workers in the facility.

The city officials who attended the meeting admitted they didn’t have solutions to offer at the meeting — but they pledged to work with the community to act on this quickly. District VII Council member Vanessa Perez, pointed out that while they now know EtO is carcinogenic, they don’t know how much of it is getting into people’s homes and into schools. That’s something that must change fast, she said. She encouraged the community to stay involved and to help the council push the state and federal regulators to get on the same page to protect their community.

Cortez assured the community at the end of the meeting that the Clean Air Coalition is committed to making sure their air is safe but warned the fight for clean air would be a marathon, not a sprint. She and others in the coalition planned to meet the EPA on Monday, December 13, she said, adding that the group would hold more town hall meetings and keep people informed.

The turnout to the meeting gave her hope, she said afterward. She believes their community will follow the example set by the community in Illinois and shut down Midwest if that is what it will take to eliminate the cancer risk from ethylene oxide.

Community members listening to presentations about ethylene oxide. Credit: Julie Dermansky