We are fighting for a future that is not riddled with anxiety and fear that another Haiyan might come anytime”, Marinel Ubaido, a survivor of super typhoon Haiyan, which hit the Philippines in November 2013, said at the final panel of COP26 in Glasgow last month.

“We do not deserve to live in fear. We deserve a hopeful future. We demand urgent action.”

Ubaido, along with the majority of those who have contributed the least to the climate crisis but suffer the most, was ultimately ignored by the wealthiest countries who dictated the parameters of the conference.

The power imbalance at the root of COP26’s failures could be seen in the mundane practicalities of attending the conference itself. Many delegates from the countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis were not even present at the conference. Small island states stressed that without vaccination, their delegations could not attend. Whilst those on the frontlines of the crisis were excluded, at least 503 fossil fuel lobbyists for some of the world’s biggest polluting oil and gas giants were granted access to the negotiations.

Other challenges included a lack of available COVID-testing facilities; restrictions on accessing the inner sanctums of the negotiation space; limited civil society observer spaces to scrutinize emerging text; and an absence of corridor influencing, where activists used to have some opportunity to review potential policy proposals. COVID safety measures were a useful proxy for narrowing the decision-making table and invizibilising the process.

These dynamics didn’t happen by mere coincidence. They were the logical outcome of a multilateral system – which includes institutions like the United Nations, World Bank and International Monetary Fund – whose nature is fundamentally colonial. It is governed by a logic of extraction, privatization and racialized exploitation. It curates a knowledge system where categories, metrics and analytics are produced by those in power. As a consequence, colonial ways of seeing and knowing constitute the evidence and analysis that define the solutions, all constructed to support the view that the richest nations at the helm of the multilateral system care and can be entrusted with solving the crisis.

Net-zero fallacies

The coloniality of the multilateral approach to the climate crisis was most evident in the cornerstone of the Glasgow Pact: the proposal to pursue ‘net zero by 2050’ to achieve the 1.5°C goal. Net zero means that instead of actually decreasing carbon emissions, those who can afford to pay can offset them through emissions trading schemes.

Global South negotiators, such as Bolivia’s chief negotiator, Diego Pacheco Balanz, asserted that this net-zero proposal was a false solution to enable a “great escape” from wealthier countries’ responsibilities to actually reduce carbon emissions. Some climate justice activists also fiercely resisted the proposal, arguing that the ‘net’ in ‘net zero’ delays and deflects from cutting carbon emissions at source while allowing business as usual to flourish through fossil fuels and industrial agriculture. They have also claimed that it could lead to land grabs that dispossess farmers, rural and indigenous communities.

Balanz said at the negotiations in Glasgow:

“Net zero is a new set of rules imposed by the North, creating a carbon colonialism. We reject the narrative that the market is the solution. We want to focus on strengthening direct cooperation from developed countries to developing countries.

“They don’t want to discuss loss and damage, only mitigation through forests which will serve as an instrument for carbon credits and effectively transfer the developed world’s historical responsibilities to the developing world.”

The net-zero policy, which allows rich countries to keep polluting at the expense of everyone else, could not be thinkable without ignoring the history that got us here in the first place.

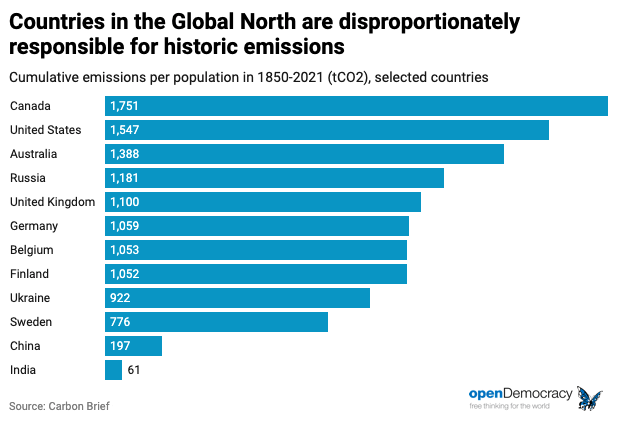

The historical context of carbon space from 1751 to 2017 shows that the US has generated 29%, of cumulative carbon emissions. The EU (including UK) has generated 22%, China 12.7%, Russia 6%, Africa 3% (of which South Africa is responsible for 1.3%), Japan 4%, India 3%, Brazil 0.9% and Indonesia 0.8%. Small island nations, whose communities endure extreme climate disasters on a regular basis, have generated so little that their emissions are miniscule in the global scheme. These numbers reveal a clarity: the Global North is responsible for occupying nearly half of global carbon space, while holding less than 20% of the world’s population.

Carbon Brief

Loss and damage

Climate finance can be directed towards three types of climate action: mitigation that reduces greenhouse gas emissions, adaptation that helps communities adapt to climate change, and compensation for loss and damage.

The Glasgow Pact is explicitly biased toward mitigation, rather than on responding to what is already happening: impacts on food security, livelihoods, economies (adaptation) and climate devastations across vulnerable regions that don’t have the various forms of capacity to respond and restore (loss and damage).

It is now generally accepted that the target wealthy countries agreed to – channelling $100bn to poorer nations each year by 2020, to help them adapt to climate change and mitigate further temperature rises – as part of the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015 has been missed. The majority of this, which the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimated was nearly $80bn in 2019 (up from $78bn in 2018) has been funnelled into mitigation projects in middle-income countries that promise investor returns – such as private financing for solar and wind energy investments in India.

Meanwhile, in Mozambique, which is considered among Africa’s nations most vulnerable to climate change, the government still relies on aid and charity for funding adaptation work, with the majority of people in cyclone-vulnerable regions living in houses with roofs pinned down by bricks.

Powerful countries also routinely double-count development aid as climate finance or label random development projects as ‘climate-relevant.’ In 2015, India’s Ministry of Finance disputed the OECD’s estimate of $62bn of climate finance given in 2014, saying that the real figure was $1bn. Given the high share of historic carbon emissions and wealth, the World Resources Institute estimates that the US should be responsible for about 45%, or $45bn, of the $100bn to the Green Climate Fund. But its average annual contribution from 2016 to 2018 was only around $7.6bn.

Since the 2015 creation of the Paris Agreement, the bloc of 134 developing countries, called the Group of 77 (G77), have been calling for ‘a mandatory provision’ of climate financing to an Adaptation Fund. At Glasgow, the US stonewalled this demand with a red line, watering the language down to merely encouraging rich countries to contribute adaptation resources, while also refusing to recognize long overdue equity for the South through finance and technology transfer.

Climate debts

In Glasgow, the G77 Chair (Guinea) repeatedly stressed that “A COP without a concrete outcome on finance cannot be deemed a success.” Bolivia also stated the plain truth of the Glasgow summit: that the continued refusal of rich and powerful countries to support the South reveals the absence of political will among the North “to address their historical responsibility and pay their climate debt to the developing world”.

In other words, with all the talk of ambition, the delivery pales. While trillions were generated by rich countries to respond to the pandemic through public financial instruments such as quantitative easing, the climate crisis, which will make the pandemic look like a dress rehearsal, cannot spin the money wheels of the North.

Meanwhile, research shows that almost 80% of climate finance is provided in the form of debt-creating loans, which have soared from $19.8bn in 2013 to $44.5bn in 2019. And 40% of these loans are non-concessional, meaning they are issued on or above market interest rates, or with shorter grace periods.

Sovereign debt is an anchor that entrenches unequal power between North and South. In 2020, 62 Global South countries spent more repaying debt than they did for urgent healthcare needs. The Jubilee Debt Campaign reveals that low-income countries spend five times more on debt than coping with the emergency of climate change. This unjust and devastating cycle demonstrates a multilateral system where the greed of international creditors (such as the IMF, World Bank, and financial corporations and commercial banks including BlackRock and Goldman Sachs) supersedes both the economic and social rights of people and the ability of the South to address climate change. On the other hand, grants, which is the form of climate finance being called for the South and by climate justice movements, amount to just 27% of climate finance, or about $16.7bn.

A new reparative multilateralism

COP26 was a stark clash of ideologies that squashed the Global South’s hopes for a future with climate equity. That clash was between leaders for and against more fossil fuels, for and against more loans instead of financial transfers and essentially those for and against the current economic system. Movements spanning reparations, Black radicalism and feminist fiscal alternatives are calling for, amongst other things, the cancelling of existing debt without attached conditions as a critical next step to enable countries to liberate themselves from the structures of colonialism and as some form of compensation for centuries of harm.

This liberation will require nothing less than revolution to combat colonial policy-making alongside the use of legal mechanisms to bring about restorative justice and reparations. It will also entail the encouragement of hopeful alternatives and the building of parallel institutions on regional and local levels. African scholar Professor Chinweizu posits the need for

“self-made repairs, on ourselves: mental repairs, psychological repairs, cultural repairs, organizational repairs, social repairs, institutional repairs… repairs of every type that we need in order to recreate and sustain Black societies.”

Multilateralism as a colonial project involves the loss of contextual and embodied knowledge, where knowing is linked to the lived experience of communities impacted by climate crises and a visceral understanding of painful loss. Dismantling the coloniality of the multilateral system begins with centering the lived experiences, Indigenous wisdoms and regenerative ways of being, practiced by communities who endure the most harm.

A new kind of reparative multilateralism is urgent for the alternative ideas it could bring to the world, and it begins with:

- A reversing of South to North financial and resource drains, starting with debt justice and a resolution that prioritizes immediate and unconditional debt cancellation.

- A scaling up of climate finance, in the form of grants not loans (to the trillions) in line with what low-income countries are asking for, with concrete commitments to loss and damage and adaptation funds.

- A prioritizing of the leadership and guidance of indigenous communities that bring us back to relational, experiential and ancestral wisdoms.

Healing can only begin when deeply entrenched hierarchies rooted in injustice and dehumanization are dismantled. Outside the confines of the current multilateral system, a plurality of knowledge is thriving. It is knowledge that will swell and flow through all the lands and rivers it can reach until it can no longer be ignored.

Teaser photo credit: By Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 – NASA Earth Observatory, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99576209