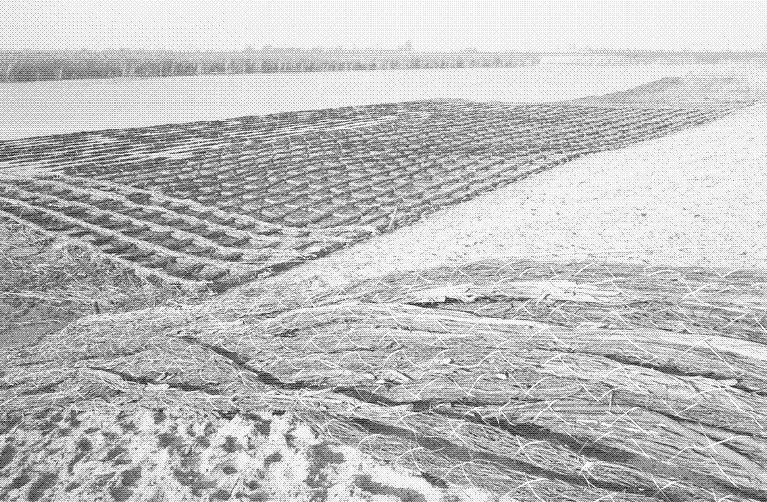

Around the 17th century, the Dutch started reinforcing their dykes and harbours with sturdy mats the size of football pitches – hand-woven from thousands of twigs grown on nearby coppice plantations. These “fascine mattresses” were weighted with rocks and sunk into canals, estuaries, and rivers.

Image: Sinking of a fascine mattress for the drainage sluices at Den oever. Source: Dienst Zuiderzeewerken, CC BY 3.0 NL. Date unknown.

Coastal and River Defences

Climate change is an imminent threat to highly populated coastal and river communities worldwide. For centuries, people have built defence structures to prevent floods and erosion: seawalls, bulkheads, breakwaters, groins, levees, dykes, and revetments. Nowadays, we usually build these structures at least partly from energy- and carbon-intensive materials: reinforced concrete (most commonly), geotextiles, steel, wire mesh, asphalt. However, people can and did build very adequate river and coastal defences without adding to environmental destruction in the longer term.

Inspiration comes – not surprisingly – from the Netherlands. The sea has been a threat in the Low Countries since long before climate change. The Dutch built their country partly at the bottom of the sea, drained it with windmills, and surrounded the new land with dykes. The Dutch coast has fine-grained, sandy soil that offers little resistance to the friction of the water. Currents, waves, and propellers of ships scour the bottom and can easily lead to the collapse of dykes, banks, quays, locks, and abutments.

Image: dyke collapse in Zeeland, near Kats on North Beveland, 1966. Public domain.

The Fascine Mattress

With stagnant or slow-flowing fresh or brackish water, planting reeds on the waterline can protect riverbanks. However, this approach doesn’t work with saltwater, nor does it prevent damage from large waves. At least 400 years ago, the Dutch came up with a solution: the fascine mattress. A fascine mattress consists of thousands of fine twigs, mainly from willow trees. These are woven together into a sturdy mat dropped at the bottom of a canal, estuary, or river. A fascine mattress can lay partly on the river-bank or dyke.

Fascine mattresses were often rectangular and of large dimensions: usually between 20 and 30 metres wide and up to 150 metres long (sometimes more). The structures were made on land, towed to their location, and then sunk to the bottom by weighting them with rubble. Everything happened by hand. Nearby coppice plantations supplied the wood for braiding the mattresses.

Image: The making of a fascine mattress, Haringvliet, 1956. Public domain.

Life Expectancy: Centuries

It’s not clear when exactly the Dutch started using fascine mattresses. The oldest image is a 1676 painting by Matthias Withoos, which illustrates the repair of a dyke. However, there are references to brushwood constructions in hydraulic engineering already in the sixteenth century. Many fascine mattresses remain functional today, centuries after their construction. Willow wood becomes rock-hard underwater and almost doesn’t deteriorate. Research in the late 1960s showed that most fascine mattresses submerged for more than 100 years — some dating from the early 1820s — remained intact.

We don’t know how many fascine mattresses are still performing their duties at the bottom of the Dutch waters, but they are basically everywhere. Most data is available from the period following World War II when the Dutch used the technology on a large scale. In 1953, catastrophic flooding hit the Netherlands. That led to the Delta Works, a series of ambitious construction works to protect the land from the sea.

Image: Fascine mattresses in the biesbosch, 1968. Public Domain.

Fascine mattresses were an essential part of this plan. For example, between 1960 and 1966, the Dutch added 200,000 m2 of fascine mattresses in the Wadden area (a group of islands in the north). Between 1954 and 1967, during works on the rivers throughout the country, they sank 1,200,000 m2 fascine mattresses to the bottom.

Braiding a Fascine Mattress

Making a fascine mattress was a craft that mainly involved knotting and braiding. In tidal areas, the Dutch braided fascine mattresses on mudflats that were dry at low tide. This meant that the work had to happen quickly. When the high tide came in again, the structure started floating – and it had to be sturdy enough not to drift apart. Finishing the fascine mattress could happen during the next low tide or even while the structure was floating.

The craftsmen started weaving brushwood into bundles or strips called fascines (“wiepen” in Dutch). Fascines were up to 50m long, had a diameter of about 30-50 cm, and were tied together with thin twigs. The fascines served to build a lower framework, which formed the basis of the entire structure. The bundles were superimposed crosswise about a meter apart and secured with rope and a pole at the crossings.

On top of this framework came a 30-40 cm “filling” of two layers of brushwood across each other. In between these came a reed layer, which made the fascine mattress sand proof. Next, an upper framework of fascines was built, identical to the lower framework, on top of the “filling”. The men then lashed the whole thing to the posts. It took about six men to build 100m2 fascine mattress.

Image: A fascine mattress. By Jan Muijs, Rijkswaterstaat, 1974, CC BY 3.0 nl.

Image: Drawing of a classical fascine mattress made out of willow wood for bed protection of watercourse. Source: Hollands’ Rijshout, Van Breen (1920).

Image: Making fascines, 1945. Unknown photographer / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image: Making fascines, 1952. Harry Pot / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: Transporting fascines, 1953. Joop van Bilsen / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: Braiding fascine mattresses, 1956. Harry Pot / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Fences

Next, the craftsmen braided fences on top of a fascine mattress by weaving more brushwood around the poles at the points where the fascines crossed and which protruded well above the upper framework. These fences further reinforced the structure and prevented rubble from rolling off the mattress. That was a risk during the sinking of the fascine mattress. The enclosure also performed its duties when the fascine mattress rested on a steep slope, for instance, a dyke. Smaller stone rubble could also be carried along by the current – fences prevented this. Finally, the men fitted a fascine mattress with drag props (arrangements of seven piles securely tying the ropes) for towing purposes.

Image: Braiding fences on top of a fascine mattress, 1950. By van Oorschot / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: Braiding the fences. Source: Zink- en aanverwante werken, benevens het hoe en de wijze waarop, B. Hakkeling, 1970.

Sinking a Fascine Mattress

Once the craftsmen had towed a fascine mattress to its destination and moored it, they sank the structure to the bottom. To this end, the workers weighted the fascine mattress with stone and rubble. This heavy work happened manually. Rows of craftsmen took place on gangways, passing 10 to 30 kg stones one by one. Workers with wheelbarrows transported the rubble from land by wheelbarrows or scooped it straight from a boat onto the fascine mattress.

At sea, one square metre of fascine mattress required roughly 200 kg of stones for sinking. Most weight was placed on the edges to prevent the fascine mattress from tipping over while sinking. Once the structure had reached the bottom, they added another 1,000 kg of heavier stones. On rivers it took less weight: only around 120 kilograms for sinking a fascine mattress and roughly 300 kilograms for keeping it in place. Finding enough stones was a lot more problematic than finding brushwood because they had to be brought in by ship from far away.

Fascine mattresses could only be sunken in a calm sea with little current, so timing was crucial. The slack tide, a period of a few minutes between low and high tide, was exploited to the maximum, even if that meant that work had to be done partly at night.

Image: Workers install fascine matttresses for the construction of locks in the Haringvliet near Hellevoetsluis, 1956. By Anefo, CC0.

Image: Sinking a fascine mattress, 1968. By Nationaal Archief, CC0.

Image: Sinking a fascine mattress, 1968. By Nationaal Archief, CC0.

Image: Reinforcing the Vlissingen boulevard, 1958. By Anefo, CC0.

Image: Reinforcing the dyke near Ouwerkerk on Duiveland, 1953. By Joop van Bilsen / Anefo, CC0.

Image: Sinking a fascine mattress. Source: Zink- en aanverwante werken, benevens het hoe en de wijze waarop, B. Hakkeling, 1970.

Image: Preparing the sinking of a fascine mattress. Source: Holland’s rijshout, L.G. van Breen, 1920.

Image: Anchoring a fascine mattress. Note the drag prop in the foreground. Joop van Bilsen / Anefo, CC0.

Overlapping Fascine Mattresses

Landing a fascine mattress in the right place was a challenge. It was difficult to sink them with precision. According to some sources, there was often 2-5 metres of space planned between adjacent fascine mattresses. Overlapping structures were to be avoided because the current could overturn the upper piece.

However, Gerrit Jan Schiereck, a retired professor in hydraulic engineering and a former employee of the Dutch public works department, disagrees with this advice: “Contrary to what some books say, it was necessary for fascine mattresses to partly overlap each other”. 1

Not all fascine mattresses were rectangles. When connecting to existing works, in river bends, and in the case of other irregularities, the structures could take the form of a trapezium or an irregular quadrangle. However, pieces with indented corners were avoided where possible.

Image: Badly dropped fascine mattresses in the bend of a river. Source: Zink- en aanverwante werken, benevens het hoe en de wijze waarop, B. Hakkeling, 1970.

Image: A collection of fascine mattresses. Holland’s rijshout, L.G. van Breen, 1920.

Tidal Coppice Plantations

The use of fascine mattresses was closely linked to large-scale brushwood production on coppice plantations. As we saw in a previous article, our forebears harvested wood by lopping trees rather than chopping them. The Dutch coppice plantations – the “grienden” – stand out because of their “wet” soils: high river levels or tidal action occasionally flooded the land. Unlike most other tree species, willow tolerates saltwater and (temporarily) wet feet. As such, the coppice plantations could use land that was not suitable for agriculture.

In 1915, roughly 14,000 hectares (140 km2) of forest in the Netherlands consisted of tidal or river coppice plantations, compared to 85,000 hectares of “normal” coppice plantations, and 155,000 hectares of tall forest. Most lay along estuaries outside the dykes and in the river areas of South Holland and North Brabant. The largest complex was in the Biesbosch. More than 200 different types of willow trees were grown in tidal and river coppice plantations. On impoverished soils, the Dutch planted alder trees between the willow trees. The falling leaves of the alder fertilised the soils and increased the lifespan and production of the willow trees.

Often, a quay surrounded tidal coppice plantations. This kept the water out during a normal tide. The plantation only flooded during storm surges in winter. Valves ensured that the water drained slowly enough to allow the sludge to settle, fertilising the soil. Ditches traversed the plantations and served for drainage – stagnant water was harmful to the trees. The workers also used the narrow canals transporting the brushwood out of the plantations by boats. River coppice plantations were inside the dykes. Here, the groundwater level – influenced by nearby rivers – determined the environment for the trees.

Harvesting the wood was just as labour-intensive as braiding the fascine mattresses. Maintenance was undertaken entirely by hand and concentrated in the winter months. The plantation workers chopped brushwood after the leaves had fallen and tied the branches into bundles. They also put new cuttings in the ground, dredged the ditches, and removed the wood. Most coppice plantation workers were day laborers at a time of the year when there was very little agricultural work. They most often slept in small shelters or on small boats on the plantations. 2

Image: Outer dyke willow field on the Oude Maas (Carnisse Grienden). By Ceinturion, (CC BY–SA 3.0).

Image: The Biesbosch in 1908. Source: Wilgenkartering in de Brabantse, Sliedrechtse en Dordtse Biesbosch, 2012-2013. Nationaal Park de Biesbosch, 2014.

Image: A tidal coppice plantation (Anna-Jacominaplaat) in 1950. Source: Wilgenkartering in de Brabantse, Sliedrechtse en Dordtse Biesbosch, 2012-2013. Nationaal Park de Biesbosch, 2014.

Image: Ditch in a tidal coppice plantation (1930-1950). Source: Wilgenkartering in de Brabantse, Sliedrechtse en Dordtse Biesbosch, 2012-2013. Nationaal Park de Biesbosch, 2014.

Image: A worker’s hut on a mound. Source: Regionaal Archief Dordrecht. (CC–BY–SA 4.0).

Houseboat in a tidal coppice plantation. Source: Regionaal Archief Dordrecht. (CC–BY–SA 4.0).

Evolution in the 1960s

Following the catastrophic floods of the 1950s, the Dutch set up a working group to find labour-saving and production-enhancing working methods. The weaving of the fascines, a job that accounted for about a third of all hours in making a fascine mattress, was the first process to be mechanised. A “fascine machine” – running on a 2 HP diesel engine – appeared in 1956. It could make 10,000 fascines per week, supplying enough material for 2,300 m2 of fascine mattresses. From the 1950s, the Dutch also used cranes and vibrating feeders for moving the rubble, and they built wharves to braid the fascine mattresses on large slopes next to the water. That made the construction of a fascine mattress independent of the tides and allowed to organise the work better. The techniques for sinking the structures also evolved.

Finally, the invention of geotextiles as adequate sand filters lowered the need for coppiced wood. This was crucial, because the existing production fields of willow in the country at the time could not supply the quantities needed for the Delta Project. The Dutch tidal and river coppice plantations served different purposes, and fascine mattresses only formed a small market. Much more important were the weaving of baskets and crates, and especially the building of hoops for making herring barrels, an important export product in the Netherlands at the time. Indeed, the Dutch used the waste materials from the hoop-making process to braid fascine mattresses. However, after World War I, iron straps and other packaging materials supplanted hoop-making from the market. Furthermore, fossil fuels made it easier to keep polders dry, so less and less land was available for coppice plantations. Of the 14,000 hectares of tidal and river coppice plantations in 1915, only 2,000 hectares remained in 1983.

The use of traditional fascine mattresses — without geotextiles — disappeared almost completely. However, they are still in use in nature reserves, and have seen renewed interest lately. Producing steel, concrete, and plastic releases carbon emissions and creates other forms of pollution too. On the other hand, traditional fascine mattresses extract carbon from the atmosphere and store it on the seafloor for a couple of centuries – without any pollution or fossil fuels.

Kris De Decker

Thanks to Gerrit Jan Schiereck, Bart Schultz, and Alice Essam.

References

De Bruin, Dick, and Bart Schultz. “A simple start with far‐reaching consequences.” Irrigation and Drainage: The journal of the International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage 52.1 (2003): 51-63.

Zink- en aanverwante werken, benevens het hoe en de wijze waarop, B. Hakkeling, 1970.

JW van Westen, Ontwerp en uitvoering van zinkwerken, 1969.

Holland’s rijshout, L.G. van Breen, 1920.

J.A.M. Schepers, Een landelijk overzicht van de grienden, 1988

Getijdenbossen, F.W. Rappard, 1971

Rijshout-, riet- en stroconstructies, J.C Visser 1954

Stroomzinken 1967-1968, H.Y. Wenning

De teelt van griend- en teenhout in nederland en het naburige vlaanderen. DWP Wisboom van Giessendam, 1878.

Geschiedenis van de techniek in nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving. 1800-1890, deel III. H.W. Lintsen, 1993.

Wilgenkartering in de Brabantse, Sliedrechtse en Dordtse Biesbosch, 2012-2013. Nationaal Park de Biesbosch, 2014.

- Phone call on 2 November 2021. ↩

- As far as I could find out, the large fascine mattress is almost exclusively a Dutch technology. However, Dutch engineers like Johannis de Rijke also introduced the fascine mattress in Japan during the Meiji period (1868-1912). Here, it was made from bamboo. Some years ago, the Japanese still used the technology in the Hokuriku region. River coppice plantations also existed in present-day Belgium (around Bornem) and Poland, but these plantations only supplied basketry materials. ↩