In recent months the world has been thrown into a global energy crisis that seems to have taken observers as well as global leaders by surprise. In September and October, wholesale prices of natural gas and electricity brutally surged in Europe, several energy providers went bust in the UK, China and then India experienced widespread coal shortages and large-scale power blackouts, and fuel prices rapidly spiked across the world. All these developments seemed to be only loosely correlated at first, but the simultaneity of their occurrence suggests that they might in fact be the various facets of something unfolding all at once across the world. Suddenly we are in the middle of a global energy crisis, or even facing a worldwide “energy shock”, as The Economist recently titled…

According to a monthly index of energy costs including oil, natural gas, coal, and propane published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the global energy price shock of October 2021 was in fact the worst since 2008, when the price of oil shot up to almost US$ 150 right before the onset of the ‘Great Financial Crisis’ (GFC). Back then the oil price however quickly collapsed in the following months as the world was sucked into a downward financial spiral. Today there are signs that energy prices may be headed higher for longer, even more than the 2008 spike. Our situation is therefore bringing back memories of what remains “the” energy crisis par excellence in living memory, that of the 1970s.

However, what we are facing today is unlikely to be just a repeat of what happened 50 years ago. The world is a very different place now than what it was back then. The causes of our energy crisis are different as well, and so are likely to be its consequences.

Not the 1970s all over again

The energy crisis of the 1970s mostly resulted from geopolitical events and tensions. The U.S., which had become increasingly addicted to oil in the preceding decades, had just passed its domestic peak of “conventional” oil production, yet there was still plenty of oil available and easily recoverable at global level – the giant fields of the Middle East were still ramping up production, and major new discoveries were still being made. The oil price shocks took place because key producing countries decided to punish the U.S. – and the West in general – for geopolitical reasons, and to leverage on this resource that they possessed and that the West needed so badly to increase their revenues and power. Today’s sudden price spikes, in contrast, are not primarily driven by geopolitical tensions, even if those are always present in the energy domain. At first sight, they result from a sudden and important mismatch between a demand for “stuff” that is experiencing a sharper than expected rebound from the pandemic lows, and a supply that is struggling to ramp up as quickly.

There has been much talk in the last few months of the global economy experiencing a “supply shock” resulting from the many and compounding disruptions to global supply chains caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, more than a supply disruption, the really remarkable aspect of what has been happening recently is a demand surge that is much stronger than what anyone expected a year ago when the global economy was struggling to emerge from a historic slump. The combination of monetary and fiscal stimulus on a gigantic scale, which was meant to cushion the shock of the pandemic, has actually triggered a rapid rise of demand for material goods that supply cannot keep up with. An interesting analysis recently issued by investment management firm Bridgewater Associates shows that the production of physical goods has actually recovered remarkably quickly from the pandemic, but that there is simply not enough raw materials, energy, productive capacity, shipping capacities, inventories, or even workers available to meet a demand that in developed economies has surged well above pre-COVID levels. Which is why prices are rising across the board for all these things…

Concerning energy, the prices of natural gas, coal, and oil are all spiking at the same time, all around the world, because demand is surging, and because, as Bridgewater notes, this demand is “eating into inventories despite reasonable levels of production”. Since natural gas and coal still represent the bulk of electricity generation worldwide, their price spikes also led to a rise in the price of electricity where electricity markets are designed in a way that amplifies the price variations of the fuels used to meet marginal generation needs (as in Europe), or to shortages and blackouts where for regulatory reasons rising generation costs cannot easily be passed on by producers to consumers (as in China).

Another key difference with the 1970s is therefore that today’s energy crunch and price spike are affecting all major sources of energy, while back then supply constraints and price shocks mostly affected just one of them. It was the dominant energy source, of course, which is why the oil shocks of that time were so consequential. Yet, in the 1970s the world could still turn to other energy sources that were less supply and/or price constrained than oil. For instance, the use of oil for electricity production dropped after the oil crisis as the power sector turned to coal, natural gas and nuclear. The use of oil for heating also peaked in in the 1970’s and declined from then on, being replaced by natural gas or electricity. The world’s use of coal thus continued to increase in the 1970s and in the following decades, and its use of natural gas grew up as infrastructure for its distribution and consumption was being deployed. Nuclear power also took up a rising share of the world’s electricity mix in the ensuing decades.

Today, the supply constraints and price shocks are not limited to oil but are affecting all sources of fossil energy, which is why we have a full-fledged “energy shock”, and not just an “oil shock” as we had back in the 1970s. Fossil fuels still represent about 80% of the world’s final energy consumption, a share that has barely changed in the last decades despite the growth of “modern renewables” (solar and wind), and all of them are engulfed in today’s energy crisis. Asia is struggling to get as much coal as it needs, Europe as much natural gas as it needs, and the whole world as much oil as it needs. Wherever you look, there just does not seem to be enough fossil fuels for the world to burn at the moment. The supply of all of them is facing rising constraints, with shrinking spare production capacity across the board. Hence there does not seem to be any real room for shifting uses between fossil energy sources, as was still to some extent possible in the 1970s.

There is still some room for ramping up nuclear energy, of course, and nuclear has actually been gaining momentum in recent months, with some countries announcing plans for investments in new generation or small modular reactors. Yet nuclear can only be a long-term option, which does not seem to be really responding to the urgency of the situation nor to the scale of the challenge, and which conveys some serious and rather inconvenient issues and questions of its own.

What lies beneath

Today’s energy shock thus results from a sudden and important mismatch between surging demand and constrained supply, yet this mismatch is probably only just the trigger of the crisis rather than its root cause. If our energy crisis just came down to that, we could hope that the disruption would be temporary, and that the situation would ease and “normalize” after a period of supply/demand adjustment. But there are reasons to think that the root causes of our crisis run deeper, much deeper, and therefore that it might be here to stay.

One underlying cause that is often mentioned is a deficit of investment in energy exploration and production, which has been going on for many years already. Investments in new oil developments dropped after the price of oil collapsed in 2014, and never really recovered – on the contrary they dropped again in 2020 due to the pandemic. A lot of those investments were simply insufficiently profitable given the level of oil prices, as well as the pressure of the fossil fuel “divestment” movement and the growing uncertainty concerning future demand. Investments in natural gas developments were also affected because the oil and gas industries are closely intertwined and because oil has historically been the major profit-maker of the two, providing most funding for investment. In addition, natural gas prices themselves have been low for over a decade, especially in the U.S. following the “shale revolution”, which created a decade-long oversupply and further undermined the industry’s profitability and investment capacity. Concerning coal, investments have been decreasing as well, even if mostly because of rising environmental concerns as well as mounting regulatory and social pressure.

The result is that, as the 2021 “World Energy Outlook” published in October by the International Energy Agency (IEA) made clear, the world is not investing enough to meet its energy needs, let alone its future needs. Investments in fossil fuels are dropping, yet this drop is not – or not yet – compensated by investments in renewable energy. Investment in oil and gas has actually gone down so much that the IEA says it is now, paradoxically, one of the very few areas that it is reasonably well aligned with the world’s claimed ambitions to reach “net zero” emissions of greenhouse gases by mid-century, but investments in renewables are still falling far short from what would be needed to power a real transition.

Competing narratives on our energy future

How did we end up in this situation, and what should we do about it? There are, broadly speaking, two main views on the underlying causes of our crisis, leading to the formulation of two types of “solutions”.

The first view consists in looking at the crisis as a “fossil fuels crisis”, resulting from our over-reliance on dirty, climate-wrecking and increasingly unreliable energy sources, which could therefore be overcome by accelerating the transition to modern renewables. Most of the remaining coal, oil and gas reserves must indeed be “left in the ground” if the world is to avoid climate change from crossing dangerous thresholds, and hence the earlier renewables will replace them the better. To this end we should be investing more in renewable energy projects, far more than what we have been doing so far. As the IEA indicates, “getting the world on track for 1.5 °C requires a surge in annual investment in clean energy projects and infrastructure to nearly USD 4 trillion by 2030”. Proponents of this view typically argue that an accelerated transition to renewables for all the world’s energy needs is technically possible, and that if done right it could even usher in a period of renewed economic growth, shared prosperity and increased equality around the globe. The only thing standing in the way, they say, is a lack of “political will”.

The second view consists in looking at the crisis as an “energy transition crisis”, resulting from our misguided, premature or excessive bets on so-called “clean” energy sources that are not yet ready to take the baton from dirty fossil fuels – and that some say will never be. The result of these bets, according to those who hold this view, is a dearth of investment in the energy sources that still underpin the global economy and power our homes, factories, cars, planes and ships, and a ruinous rush towards intermittent (and seasonal) energy sources that remain too unreliable to power a modern economy. Look at China, they say, where massive investments in solar and wind in recent years have obviously failed to significantly reduce the country’s gigantic need for coal. Look at Europe, they continue, where a persistent lack of wind in recent months caused a surge in demand for natural gas for electricity generation, which in turn is what sent gas and electricity prices soaring. The proponents of this narrative generally suggest that what we need now is to slow down on renewables investment and deployment and to shift our focus and efforts towards energy security instead by reinvesting massively on fossil fuels, even if temporarily.

These two narratives currently dominate the conversation about the world’s energy situation and future, yet they are inherently partial and misleading, and the “solutions” that are commonly advocated are therefore largely misguided.

The first narrative – we can transition away from fossil fuels to renewable energy quickly if we have the political will, and we will all be better off if we do! – is unfortunately “energy blind”, to use a term coined by American systems thinker Nate Hagens. It is based on a well-meaning yet misguided faith in human agency, and on a misunderstanding or even an ignorance of how energy shapes and conditions the development of human civilization. The defining driver of this development is indeed an endless quest for more and/or better forms of energy inputs, which is how we expand and improve the outputs we obtain from our “exosomatic” (out-of-body) energy use – which, in turn, is how human societies acquire power over others and dominion over their environment, but also how they “grow” and “progress”.

In that endless quest, there are three key patterns that can be observed so far. The first is that human civilization gobbles up ever more energy to keep growing and expanding. Our use of energy has been increasing ever since we discovered and mastered fire and developed agriculture, but mostly since we gained access to a vastly increased energy supply by extracting millions of years of stored and concentrated solar energy from the Earth’s crust in the form of fossil fuels. Combined with the development of new energy conversion techniques, this energy bonanza made it possible to lift the secular barriers to human population and output growth. The new energy sources, forms and uses that came online since the turn of the 19th century gave us access to more materials and enabled the invention of new and increasingly sophisticated exosomatic instruments (i.e. machines), which in turn made it possible to access ever more energy and matter and to transform them ever more effectively and efficiently. This resulted in a rapid rise in our total energy and material “throughput” (i.e. the flow of raw materials and energy from the biosphere’s sources, through the human ecosystem, and back to the biosphere’s sinks), which is what we commonly measure through the proxy concept of “economic growth”. This rise never stopped since then, even if the global distribution of the flows of energy and material inputs, outputs and wastes evolved over time. Our efforts to increase the “energy efficiency” of our machines and processes (i.e. reducing the amount of energy needed to perform certain tasks) never resulted in a reduction of the total energy we used, but on the contrary only contributed to create more room for increasing the rate of our consumption.

The second historical pattern that can be observed is that as they grow their energy use, humans never really “transition” from one energy source to another – as least so far. Historically, new sources of energy may have displaced pre-existing others as the dominant ones, but they have never really substituted them, just supplemented them. In fact, in absolute terms we are today using more of any energy source than at any time in human history – including water, wind power and biomass that were the dominant energy sources before the fossil fuel era. Only the relative composition of our energy mix has evolved over time.

The third historical pattern is that new energy sources only come to supplant pre-existing ones in relative terms when and because they happen to be “superior” to those in terms of energetic quality (i.e. capacity to be converted into “useful work” through exosomatic devices and infrastructure) and of energetic productivity (i.e. capacity to provide usable energy in excess of the energy consumed in the extraction/transformation/transport and delivery process). The reason why fossil fuels came to dominate our energy systems to such an extent is not just because of their abundance but because they were incomparably “superior” in energetic terms (i.e. more energy dense, more powerful, more economic, more convenient and versatile) to anything we had been able to use before them, and the reason why they still dominate our energy systems so outrageously is because they are still largely “superior” in energetic terms to anything we have discovered since then (and that includes nuclear as well as renewables).

This “superiority” is why fossil fuels provided the foundation upon which the modern world was built, the essential basis for the development and growth of the modern human economy, but also for the advancement of human “progress” in all its dimensions – which includes, among others, the fact that there will soon be 8 billion of us on the planet, that a significant share of us can enjoy a level of material prosperity and security that would have seemed unimaginable just a few generations ago, and that some of us can even benefit from a degree of physical, psychological and political freedom unlike anything that has existed at any time in human history. All of this would not have been remotely possible, or at least not on such scale, if there had been no coal, no gas and especially no oil in the Earth’s crust. Contemporary human progress, fundamentally, has been a fossil-fuelled process.

On all the aspects that determine or influence energetic quality and productivity (energy density, power density, fungibility, storability, transportability, ready availability, convenience and versatility of use, convertibility…), solar and wind energy do not seem to be “superior” to fossil fuels in the same way as fossil fuels were to pre-existing energy sources – in fact they rather seem to be significantly “inferior”. Biophysical examination as well as empirical evidence so far shows that the capture of diffuse and intermittent energy flows and their conversion to electricity through man-made devices is, inherently, an imperfect substitute for the extraction and burning of concentrated energy locked up in coal, oil and gas, and hence that it might not be able to provide the same services and value to society or not on the same scale. Unfortunately, no amount of “innovation” seems to be likely to fundamentally change that.

In the light of the patterns that have been defining our energetic and civilizational course on this planet so far, the expected total or partial replacement this century of fossil fuels by renewable energy sources would constitute a systemic change without any kind of precedent in human history. Even more, it would represent a fundamental reversal of humanity’s energetic course. From an energetic but also economic point of view it would not represent an upward transition, but rather a downward one, i.e. a move towards a lower quality and lower productivity energy system, only capable of supporting a significantly reduced population and economic footprint. Many of course hope that we may be able to compensate this downward shift by somehow “decoupling” economic growth or at least prosperity and wellbeing from energy and material throughput by increasing energy efficiency and material recycling, yet there is no empirical evidence supporting the existence of any absolute decoupling so far anywhere in the world, nor any real prospect that such decoupling may actually happen in the future.

In Western societies we have reached a point where we want to believe in the unbridled power of human agency, at individual level (“I can be whatever I want to be”) as well as at collective level (“we can do whatever we want to do”). Self-actualization and “political will” have become the modern myths of the Western psyche… Yet even with a lot of faith in the power of political will it would be quite extraordinary if we could in fact decide, collectively and at global level, to enact in just a few decades a systemic change without precedent in humanity’s history and that would fundamentally reverse our species’ energetic and economic course. If we would in fact make that choice, we would quickly find out that we would not just be letting go of the downsides of fossil energy, but of most of its upsides as well – which would probably make it extremely challenging to sustain our choice over time.

If the first narrative about our energy crisis is thus “energy blind”, the second one – we should slow down on the costly transition to unreliable renewables and rather invest more in securing adequate fossil fuel supplies to feed our economic growth before realistic alternative solutions are available – is “ecology blind”. It somewhat grasps the physical limits of renewables, yet it ignores the consequences for the world’s climate – and the environment in general – of trying to maintain our reliance on fossil fuels for a bit longer, but also the inherent economic and social risks of clinging to energy sources that are in the process of getting depleted. Indeed, much more than the effects of a too slow or too fast transition to renewables, fossil fuel depletion is what constitutes the background to our energy crisis and the reason why it is probably here to stay.

Just like all non-renewable natural resources, fossil fuels are stock-based, exhaustible and subject to depletion. As their use increases their reserves get depleted, which tends to impose rising constraints on the quantities and costs of the resources that can be obtained, but also to degrade their quality. In fact, depletion means that over time it inevitably gets more and more difficult, costly, resource-intensive and polluting to get fossil fuels out of the ground, and that the energetic quality and productivity of what is extracted tends to go down, resulting in a decreasing capacity to provide ‘”surplus energy” to society and to power useful and productive work.

Of course, the effects of depletion can be counterbalanced by technological progress, but only up to a certain extent and for some time. For instance, the “shale revolution” in the U.S., made possible by new or improved techniques (hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling), allowed the world oil production to keep rising after the global peak of “conventional” oil production was reached around 2008, yet it has already largely played out and is unlikely to be sufficient to make up for the depletion of conventional crude moving forward – especially when the giant fields in the Middle East go into decline, which could occur in the next decade or so. The effects of depletion may of course also be countered by a rise in the price of energy resources and a concomitant increase in the efficiency of their use, but there again only up to a certain level and for a certain period of time, beyond which it crushes demand and leads to a price collapse. Depletion, as it unfolds, inevitably degrades over time the return on investment of new energy exploration and production, and hence progressively depresses investment. Depletion, and not just the effect of climate policy or price variations, is fundamentally the reason why investment in fossil fuels is trending down and will continue to do so in the future. As pointed out by American energy analyst and author Richard Heinberg, persistent, accelerating fossil fuel depletion is really what lies behind the headlines about our worsening energy crisis. Even putting the climate emergency aside, it certainly is not in our interest to try to maintain our dependency on fossil fuels, or we risk seeing them leaving us long before we are ready to leave them.

The two competing narratives that currently dominate the conversation about our energy situation and future are therefore, each in their own way, “reality blind”, in the sense that they are unable to grasp the reality of our situation, in all its dimensions and complexity.

Transition? What transition?

Where does this leave us and what does it mean for our energy future? Is the gathering energy crisis going to trigger an acceleration of the transition away from fossil fuels – or on the contrary hamper it? Only time will tell, of course, yet there are signs that the crisis may slow down the pace of deployment of renewables rather than accelerate it. In fact, the rising price of fossil energy is now triggering a significant spike of the production costs of both solar cells and wind turbines, which is putting numerous deployment projects at risk. Fossil fuels are indeed used extensively along the whole value chains of solar and wind, both directly (for manufacturing, transporting and deploying solar panels and wind turbines) and indirectly (for extracting, processing, refining and transporting all the elements and producing all the components that are needed to do so), and so far there is absolutely zero empirical evidence that modern solar panels and wind turbines could be produced and deployed without these fossil fuel underpinnings and inputs. This, by the way, clearly shows that not only is there is not yet any “transition” away from fossil fuels and into renewables underway, but that modern renewables so far only exist as an extension of – or an add-on to – fossil-fuelled industrial and technological society. This also means, of course, that when fossil energy becomes scarcer and more expensive then renewable energy becomes more expensive as well – which is exactly what seems to be happening now as the price of solar panels and wind turbines is going up.

There has been much talk in recent years of the rapid drop in the costs of solar and wind and of how this drop was the result of a technological “learning curve” that would continue far into the future and make their growth unstoppable. What is happening at the moment with the sudden rise of renewables’ production costs shows that this drop was in fact essentially a result of fossil-fuelled globalization (that is, of the transfer of manufacturing to low-cost countries enabled by the wide availability of cheap energy and material inputs and resulting in the massive concentration and scaling up of production). When this fossil-fuelled globalization hits a snag then the cost curve of renewables is thrown into reverse. Of course, there are still plenty of analysts around claiming that renewables will make energy cheaper and cheaper for ever, yet these claims are likely to become increasingly difficult to square with reality in the coming years.

In fact, the belief that making solar and wind cheaper than fossil fuels for power generation would make the energy transition unstoppable was probably always mistaken to start with. First because any comparison between the relative cost of a renewable power system vs. a fossil-fuelled power system can only be meaningful at system level, meaning if it includes all costs incurred for delivering a same end product, i.e. not just some electricity, but electricity that is available 24/7, without interruption or variability, 365 days a year – which is what end-users demand and what fossil fuels can provide. To do so, the comparison would have to include, on the renewables side, and in addition to the cost of generation per se, the cost of the necessary storage, plus the cost of required transmission grid upgrades and adaptations, plus possibly the cost of necessary “demand-side management” measures, if any. It would also have to factor in the possibly non-linear evolution of these costs at different scales and penetration rates, as well as the costs resulting from the rising complexity of an increasingly electrified and decentralized energy system. When taking such a system view, fossil-fuelled power generation probably still retains a significant cost advantage over renewables, which is why electricity costs for end-users so far tend to rise when and where the penetration of solar and wind increases.

In addition, the very idea that cost might be the main driver of investment is erroneous – in a capitalist economy it never was and never will be. As pointed out by political economist and economic geographer Brett Christophers, the nub of investment in a market-driven economy is not cost but profit, and what matters most for boosting investment in renewables is therefore not so much their relative cost vs. fossil fuels but their relative profitability. Typical investments in oil and gas projects continue to earn returns that remain significantly higher than those of renewable projects, due to the fact that barriers to entry are much higher for fossil fuels, but most fundamentally to the fact that the energetic quality and productivity of renewables is inherently “inferior”. The relative profitability disadvantage of renewables can of course be partly counterbalanced by policy and regulatory measures, but only up to a certain extent, and at significant cost overall for the economy.

Hence, renewables are unlikely to become ever cheaper, as we keep hearing, and even if they do that would still be insufficient for the world to turn its back on fossil fuels. Our energy future, as a consequence, is unlikely to be one of superabundance of dirt-cheap clean energy, as some techno-optimists now claim. Rather, it’s likely to be one of increasing scarcity and rising costs. Increasing scarcity and rising costs of fossil energy – as a result of the relentless, inescapable and mounting impacts of depletion and of its consequences (i.e. lack of investment, erosion of spare production capacities, weakening and breakdown of supply chains). Increasing scarcity and rising costs of energy in general, as the relentless addition of supposedly cheaper alternatives to fossil fuels keeps in fact increasing the overall cost and complexity of our energy systems.

Energy being used for doing and producing everything, these rising costs will likely ripple through the economy and feed inflationary pressures in years to come. However, a return of 1970s style “stagflation” (i.e. a prolonged combination of low economic growth and high inflation) seems unlikely at this stage. Back in the 1970s, rising energy prices generated a sustained inflationary cycle essentially because the bargaining power of workers was higher than it had ever been and hence a powerful wage-price spiral was triggered in the wake of the oil shocks. At the same time, rising prices slowed down the economy for a prolonged period without really crashing it, partly because the fossil-fuelled expansion of the preceding decades still had some steam left, and also because its substitution by a debt-based growth model was only beginning and credit was starting to boom. Today, the bargaining power of labor has been crushed, and even if staff shortages are fuelling wage rises in some sectors at the moment, this is unlikely to result in a sustained wage-price spiral. Already, demand growth seems to be slowing down and cracks are appearing in the global recovery.

In addition, rising prices, if they were to persist for a prolonged period, would not just slow down the economy but risk crushing it through demand destruction as the global economy has no real steam left to compensate their effects. After five decades of relentless credit expansion, the global debt-based growth model has largely run its course and there is little room left for further credit growth. In fact, the whole global debt-based financial edifice is only really holding because the world’s largest central banks have been engaged for years in an exercise in perpetual bankruptcy concealment. If inflation was to rise further and prove persistent, these central banks would probably have to raise interest rates to try to tame it, which in a world overloaded with debt would inevitably risk triggering a mechanism of debt deflation that would quickly send the economy into recession and stop the inflationary spiral in its tracks or even reverse it.

Hence, if the overall trend of energy prices is most certainly up in the coming years, the rise is unlikely to be continuous and uninterrupted. Rather, periods of rapid price increase could be followed by sudden crashes, meaning that what is likely to dominate is price volatility rather than sustained inflation, and economic instability rather than stagnation. We have entered the age of global energy disruptions, and most likely will never really get out of it.

The world, our world, finds itself caught between a rock and hard place. The relationship that we humans have developed with fossil energy over the last 250 years is a textbook definition of an addiction, and increasingly looks like a Faustian pact: we know that it’s slowly killing us, we know we should be leaving it in the ground and we also know that we will someday have to live without it anyway, yet we just can’t stop burning it and we can’t get enough of it, because we have multiplied our numbers and built our whole world around it. The detox “replacement medications” that we are using do not seem to be working so far, even as we keep increasing their doses. We are of course “pledging” to try harder and harder in the future, yet we keep relapsing into our fossil addiction, year after year, day after day, one flight at a time, one car ride at a time, one purchase at a time, one degree of comfort or of convenience at a time. By doing so we keep turning our eyes and minds away from the real nature of the upcoming and inevitable “energy transition”, the only one that is in fact likely to happen in our lifetimes, and which as Richard Heinberg said will almost certainly be a transition “from using a lot to using a lot less”.

This paper was commissioned by the Crans Foresight Analysis Nexus with funding from Omega Resources for Resilience

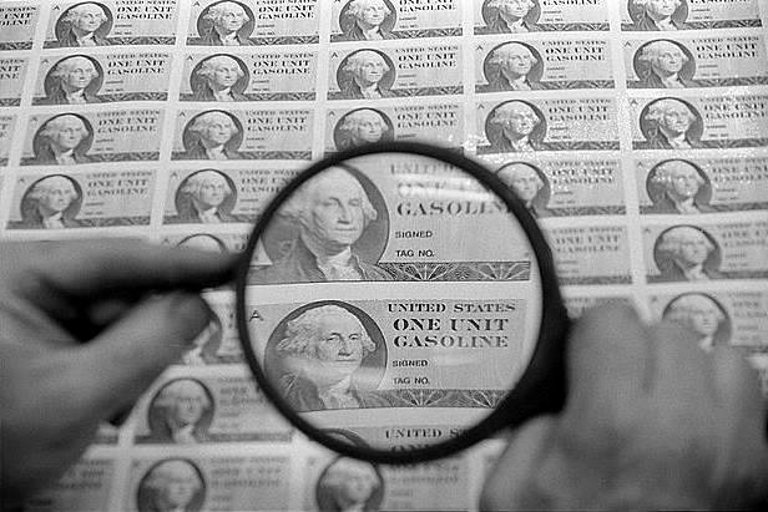

Teaser photo credit: Gasoline ration stamps printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 1974, but not used. By Leffler, Warren K. – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs divisionunder the digital ID ppmsca.03428.This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing for more information., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5762112