Earth scientist David Hughes—who is out with a new skeptical report on the future of U.S. shale oil and gas—has two very important things in common with Michael Burry. Burry is the investor made famous by The Big Short, the book that was later turned into a movie of the same name about the 2008 housing crash.

Both men made calls that contradicted an almost unanimous consensus, and both did so after dogged, painstaking research.

First, let’s look at the latest from Hughes, an update on the U.S. shale oil and gas industry entitled “Shale Reality Check 2021.” Then, we’ll return to his previous prescient call.

“Shale Reality Check 2021” seriously undermines rosy long-term forecasts made by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) for U.S. oil and natural gas from shale deposits. This matters because the EIA’s forecasts are counting on shale for 69 percent of all U.S. oil production from 2020 to 2050 and 77 percent of all U.S. natural gas production in the same period. And, it matters to the world because between 2008 and 2018, growth in U.S. oil production accounted for 73 percent of the entire growth in global supplies. (Oil from shale deposits is properly known as “tight oil,” a type of oil also found in other kinds of rock. Natural gas from shale deposits is typically referred to as “shale gas.”)

Hughes’ conclusions are based on commercially available drilling and production data. Here are his overall findings:

-

- Of the 13 major plays he evaluated, Hughes rates the EIA’s production forecast for five as “moderately optimistic,” five as “highly optimistic,” and three as “extremely optimistic.” The EIA forecast for the Wolfcamp Play, the largest tight oil play, is rated as “highly optimistic.” The forecast for the Marcellus Play, the largest shale gas play, is rated as “moderately optimistic.”

-

- Future production will likely be much lower than the EIA projects—particularly in the latter part of the 2020 to 2050 period as sweet spots responsible for most of today’s production become saturated with wells.

- U.S. energy policy and planning in such key industries as transportation, utilities and chemicals are based on the EIA’s excessively optimistic forecasts. Since oil and gas constitute 71 percent of the current U.S. energy supply, if future oil and gas production disappoints, as Hughes expects, look for serious problems.

Hughes’ prescient call

So, why should we pay attention to Hughes’ latest take on U.S. tight oil and shale gas?

We should because in a move similar to Michael Burry’s prescient call prior to the housing crash, Hughes released a damning and prescient analysis of the Monterey Shale. The Monterey Shale is an underground formation in California that the EIA touted as containing 15.4 billion barrels of recoverable oil. Hughes wrote that the EIA’s estimate was likely to be “highly overstated” for reasons he detailed in a 2013 report.

The following year the EIA stunned the industry, investors and California officials with a 96 percent reduction in estimated tight oil resources for Monterey—a virtual wipeout. Prior to the downgrade Monterey comprised 60 percent of all U.S. tight oil resources.

So, how did Michael Burry and David Hughes both achieve such prescient calls? It turns out that they simply bothered to look.

Burry looked at thousands of individual mortgages tucked inside mortgage bonds. He came to the conclusion that a large portion of those mortgages were poor quality and would default in a housing downturn, something he expected was coming. Burry subsequently shorted the bonds and made a fortune.

Hughes—who assessed Canada’s coal and unconventional natural gas resources during his previous 32-year tenure at the Geological Survey of Canada—analyzed data for thousands of individual tight oil and shale gas wells to see how the U.S. industry has actually been doing. The story his analysis generated in 2013 and the trends it is revealing today tell a far different tale than the one the industry and the government are communicating to the public.

Greatly overestimated

So, why does Hughes believe the EIA has greatly overestimated recoverable U.S. tight oil and shale gas resources? Let us count the reasons:

1. Highly productive “sweet spots” are a small proportion of what are often depicted as very large plays. In his report, Hughes plots existing well locations and looks at initial production rates from those wells, rates which foretell ultimate recovery totals. The geographic concentration of wells with high initial production rates clearly demonstrates that typically only 20 percent or less of the various shale plays comprises the “core areas” or “sweet spots.” Outside those core areas, production rates and recoveries are substantially lower.

In its forecast the EIA makes an estimate of average recovery per well over the entire play or in some cases over broad subareas within a play. In response to emailed questions Hughes wrote, “Assuming that all wells will produce the same over broad areas, as the EIA does, does not reflect the actual geology of typical plays.”

2. Worsening geology ultimately trumps technology. The average oil and gas production rate for new wells has begun to fall in all or parts of several shale plays. Hughes said that “eventually average new well productivity falls in all plays even with better technology as all the well locations in ‘sweet spots’ have been drilled and new wells are moving into poorer quality geology.”

This is a key point. New technologies are not overcoming “poorer quality geology” and the challenge will become steadily greater as drilling moves into progressively lower quality areas of the various plays. At some point the industry will give up. Hughes noted, “Industry has no interest in drilling low quality rock and is very good at avoiding doing this or they go bankrupt.”

3. Wells can only be so close together. The density of wells is reaching the saturation level in many of the core areas. Adding wells will only cause well interference and reduce per well production without increasing ultimate recoveries.

Impressive gains in well productivity have come as a result of technology that allows one tight oil well to access three times the reservoir volume of a tight oil well drilled in 2012. One shale gas well can now access 2.2 times the reservoir volume of a shale gas well drilled in 2012. (These numbers were calculated for a previous report written by Hughes.)

However, as new wells drain a much larger area than wells drilled even a few years ago, those new wells require considerably greater spacing so they won’t interfere with one another. This dramatically reduces available drilling locations, something the EIA has not taken into account in its forecasts to date. In other words, the EIA should not be multiplying its current estimate of total possible well locations by recoveries from these newer wells without dramatically adjusting the number of well locations downward to account for the increased well spacing required.

The 2021 report states that “[a]lthough this [new technology] has increased well productivity and hence economics, it has reduced available drilling locations must faster, raising serious questions about the EIA’s forecasts for production through 2050 if not much sooner.”

4. The rate of technological improvement is slowing. The EIA believes that recovery technology will improve at the same rate it appears to have improved in the past. The agency fails to recognize that better technology cannot make up for deteriorating geology as new drilling moves outside of sweet spots.

Engineering and economic limits appear to have been reached for increased lateral lengths (horizontal extensions of wells) and volumes of injected water and proppant (specialized sand and additives that prop open fractures made by water injected into the reservoir and that thereby facilitate oil and gas flow—a process known as hydraulic fracturing or “fracking”). Observed gains in well productivity are now largely due to high-grading, the practice of exploiting the most productive areas of a reservoir first. Failure to recognize this practice mistakes exploitation of the most productive areas for technological progress.

5. High decline rates will inevitably overcome increased drilling rates and production will fall. As drilling moves out of sweet spots into progressively lower quality parts of the reservoir, well productivity declines. Assuming drilling locations are available, that means more new wells are required than before to offset a given amount of play decline. Eventually, new well productivity drops below the level that makes it profitable to drill new wells. Drilling stops and the play goes into terminal decline.

The 2021 update states: “The nature of tight oil and shale gas plays…is that they decline quickly, such that production from individual wells falls 75–90% in the first three years, and first-year play decline rates without new drilling typically range from 25–50% per year.”

The update later adds: “As sweet spots are exhausted, drilling will, of necessity, have to move into lower quality parts of plays, meaning higher prices will be required to break even. Drilling rates will also have to increase to maintain production, which will consume drillable locations faster….”

Same data, different conclusions

While the EIA and Hughes draw from the same data for their analyses, they come to very different conclusions. Hughes said the EIA “is somewhat political and good news sells, so they are typically very optimistic on long-term production.”

Hughes added, “[The EIA does] the American people no favors by putting out overly optimistic forecasts. Planning for future energy security requires the best possible estimates.”

To get a sense of what the future holds for U.S. tight oil and shale gas, Hughes suggested looking at the Barnett Shale in Texas where the shale revolution began.

He explained: “The Barnett Shale is where ‘fracking’ was developed by [George] Mitchell in the 1990s. It went through the full cycle—drilling off sweet spots, spreading out to poorer quality areas with decline in new well productivity to uneconomic levels, and a gradual fall in overall play production at terminal decline rates as very few new wells were being drilled. Production has declined 60 percent since the play peaked in 2011.”

Hughes thinks we are headed into a future foretold by the Barnett Shale much sooner than the EIA will admit and policymakers and the public realize. We are not ready for that future.

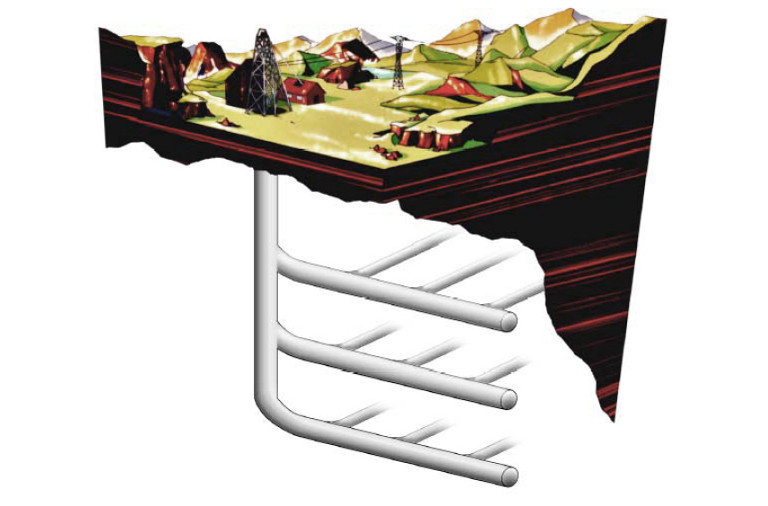

Image: Artist’s rendition of a shale oil extraction process using radio waves. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (2006). Via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oil_shale_radio_frequency_extraction.JPG