This article is the first in a four-part series we’re launching this week on American alleyways as promising sites for incremental infill development. The author, Thomas Dougherty, will be the guest on Thursday’s episode of The Bottom-Up Revolution podcast. And stay tuned for the e-book we’ll be releasing at the end of the week, which will feature bonus content not shown on the website!

It is rare to find a street in America that does not seem to be almost wholly oriented around the movement of cars from one point to another. The street understood as part of the public realm seems to be forever lost, a thing of the past. There are political and cultural reasons for this, and a long history of how this came to be, well told by authors including Andres Duany (co-author of Suburban Nation), and James Kunstler (The Geography of Nowhere). Perhaps the most fundamental reason for this, though, is that most American streets—both historic and modern—are very wide, at least compared to streets of historic European towns and cities.

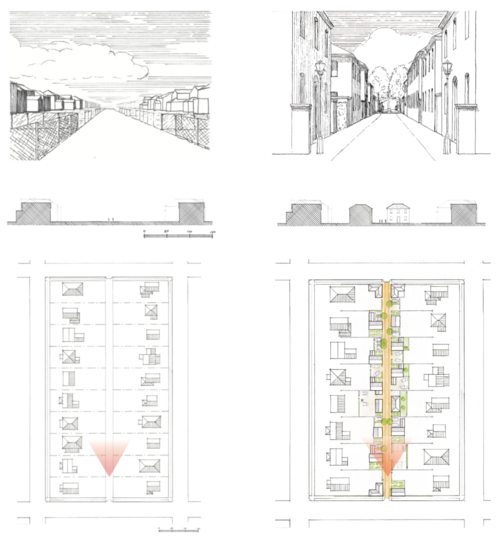

Two defining spatial characteristics of the modern street, specifically in America, are their size in relationship to pedestrians and their lack of spatial definition. (Modern American streets aren’t framed by buildings. If urban space is the “room” of a city, the room is missing walls.) The “minor streets” of Philadelphia, as we will see, offer a striking exception.

For almost half a century, architects and urban planners have worked toward transforming the modern auto-centric street to a more person-centric one. Their efforts, and especially the work of the members of the Congress for New Urbanism, have made huge strides toward bringing awareness to the general public of the inhuman nature of the modern city, specifically embodied in the modern street. However, the non-pedestrian scale and lack of spatial definition remains a vast, regrettable divide between almost all of today’s streets, and the streets that make up the historic towns and cities of Europe and the minor streets of colonial America.

In this series of articles, I will attempt to lay out a model for the incremental infill development of existing American towns and cities, at a human scale and in a spatially defined manner. This model is the development of the inner block. Inside traditional urban blocks are many types of public, semi-public, and private spaces fronted and formed by buildings and walls. That’s the inner block, and it’s perhaps best recognized in the form of your basic courtyard. This is perhaps the only place in many American towns and cities today that will allow the development of pedestrian-scaled urban spaces—most easily seen along the residential alleyway.

The American service alley, running through the center of a traditional urban block, was created at a time when city infrastructure looked radically different. Back then, the alley was home to the less-sightly aspects of daily life. Horses, necessary for most transportation, were stabled there, along with the vast amounts of manure they produced. Latrines were located along alleys, where they were periodically emptied by those employed in night soil removal. Firewood and later coal used for heating and cooking were delivered from alleys. Commonly, the “backyard” was also the place where water wells were dug and cooking was done. By the early 1900s, as these forms of services were displaced by more modern infrastructure, the essential utility of the service alley was lost; by the 1930s it was generally no longer platted. In the automobile-dominated world of the 20th century, the alley became home to small garages, parking, and trash pickup. But in recent years even those have been moved to the front street. The infrastructure that once required the space of the service alley (electric wires, natural gas, fresh water, and wastewater) now fits within a cavity wall. Urban alleys today are often abandoned or hardly used.

“Out of Sight and Out of Mind”

American service alley rights-of-way are typically 16 feet–24 feet wide, measured from property line to property line. Garages and outbuildings along the alleys are often built on the property line or with relatively small setbacks, making the distance from building face to building face quite narrow in comparison with those on the primary streets. To walk down an alley is to get a sense of the human scale and potential for spatial containment found nowhere else in the city.

Holly Alley, West Chester, and Panama St., Philadelphia, at the same scale.

Alleys and rear yards (the space between the primary structure and a rear alley) make up huge amounts of land in American cities. In Chicago alone, there are 1,900 miles of alleys—enough to stretch from Chicago to Los Angeles. A 2010 study by Gehl Architects pointed out that there were 217,500 square feet of alleys in downtown Seattle, mostly vastly underutilized, as well as 456,390 square feet of public parks, squares, and pedestrian streets. “By seriously considering our alleys as potential for great public spaces within the city,” the study concluded, “we can increase our public space by 50% in downtown Seattle alone.” As we will see in Part 2, the service alley is an artifact of an earlier era that had different practical needs. Many cities, no longer seeing the ROI on all the maintenance costs, have simply let them become grown over. Others have de-platted them, striking a new property line down the center and giving the land to the adjacent property owners.

And it’s not only the service alley right-of-way that is underutilized. Rear yards and alleys, especially in residential neighborhoods, often claim as much land between buildings as the front yard and street.

From service alley to minor street.

In 1978, in an effort to stop the city’s demolition of St. Louis’s alleys, Grady Clay authored Alleys: A Hidden Resource. In it Clay wrote,

“Out of sight and out of mind, the American residential alley has been the academic, geographic and social outcast of the built environment for at least half a century… The literature on alleys is rudimentary, to say the least, and it is now time to consider what the alley is, and what it might become—a hidden resource waiting to be recognized.”

The American alley is a resource that has been “out of sight and out of mind,” but it is now one that offers an opportunity for dramatic, value-enhancing redesign and development in many of our towns and cities. Improving alley and rear yard design can be approached at the scale of the individual lot, by a homeowner working independently of neighbors and city; or on a citywide scale, as we reconsider alleys as a network of secondary pedestrian streets. Or, perhaps best: somewhere in between, in which a creative collaboration between homeowners and the city allows for individual choice and initiative within a unified vision of the public realm.

Alleys and ADUs

American demographics are changing and so are housing needs. According to a 2017 exposition held by AARP and the National Building Museum, entitled “Making Room: Housing For a Changing America,” 28% of the American population is single people living alone. Yet almost 90% of the nation’s residential units consist of two or more bedrooms. Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) were highlighted as one of the greatest potential resources to address the need for smaller residential structures. For towns and cities built according to the traditional development pattern, this often means ADUs along alleys.

Over the last century, the vast majority of municipalities in America have severely restricted, or made illegal outright, the building of a second dwelling in the backyards of single-family homes. That is beginning to change. For example, in 2017 California began the process of legalizing ADUs statewide. For towns and cities across the country, ADU legalization is making inner block development possible for the first time.

“Just as the housing needs of individuals change over a lifetime, unprecedented shifts in both demographics and lifestyle have fundamentally transformed our nation’s housing requirements.” –AARP

Transforming American alleys into streets through the development of ADUs would begin to create the density needed to support highly desirable, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods. Alley residential streets would be small, prompting the construction of narrow townhouses, coach houses, and apartments over garages or workspaces. They would help address the housing crisis, providing a home for those who do not want or cannot afford a larger, detached single-family home. The new narrow streets could form a secondary street network designed around walking and biking, providing freedom and independence for the young, the old, and those who do not have a car. Alley homes would be less likely to fall prey to rapid gentrification and land speculation, since the lots they are developed on are already privately owned. Slow incremental development with a range of building types and uses will be enabled through the patient capital of a homeowner. As secondary buildings, incremental development and flexible uses would be encouraged. The defined streets could provide a character of prioritizing (or perhaps only being accessible to) pedestrians.

The historic, tree-lined American “major street” is a wonderful urban space. Creating a more diverse urban fabric around it by developing smaller, mostly pedestrian “minor streets” will only enhance the appeal of the neighborhood.

In the next installments of this series we will look at the rise of the American alley (Part 2), and its fall (Part 3). In the final article, we will see that, together, the revival of ADUs and alleys can play an important role in addressing a host of issues in our communities today. The thesis is not that all American alleys should necessarily be lined by townhomes and coach houses. Rather, transforming an alley into a secondary street is historically a process of maturing urban fabric, and through this transformation, critical needs of American cities and communities can be better met.

All images provided by the author.