ABSTRACT

Hammers, Nails and New Constructions – An Obvious Case for Economic Pluralism

A ruling orthodoxy in academics is pathological, symptomatic of models unfit to their realms of use. Substitution assumptions do not apply in a complementary setting. Pluralism ought to be normal; this is not the case.

Choices are based on imagined projections whose costs are invisible, limned theoretically yet unobserved. ‘If all we have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.’ Substitution assumptions say our relations involve a conflict of interests. A network model opens a choice: competition or cooperation, which is more efficient? The notion of planning horizons shows how longer horizons enhance common over conflicting needs, with an ordinal index of rational limits. If learning is complementary, an efficiency case for cooperation is supported by horizon effects.

Applications are explored, to show failures of competition in complementary settings: in ecology; education; information networks; and in the myopic culture wrought by competitive frames. Scientific control leads to rigid dogma in academics; science should be open as an axiomatic condition. Pluralism helps to avoid theories unfit to their realms of use. We need to forego our hammers and nails and try on new constructions.

I. Introduction

Orthodox standards in academics suggest an incentive failure in our research institutions, rising from economic concepts ill-fit to their realm of use: substitution does not apply in complementary settings. First, multiple models show the invisible limits of each, shielding us from mistakes that we cannot otherwise see. Orthodox substitution assumptions do not reflect our relations.

The rigid, dogmatic character of economics stems from its stolid devotion to competition as efficient. Narrowminded dogma is blind to its own exclusions, so to its opportunity cost. The case for pluralism means efficiency in the growth of knowledge. Competition in complementary settings shall lead to incentive failures, such as in ecology, education, information and culture. Rigid dogma in economics is symptomatic of a pathology rising from models unfit to their use. Pluralism ought to be normal; this is not the case.

II. The Nature of Choice

We do not choose outcomes, but among imagined projections thereof standing on models of how the world works. Every view is selective, focused on what it deems significant. No insight is provided to any ignored domain. The essentials of an approach are asserted; they appear in its use.

Opportunity cost is the value of what we forsook: cost is invisible. We only get one world, and lose all we forego. The only way to assess well-being – against unexplored options – is through a theoretical lens.

A good way to think about rationality is as a measure of fit between models and their realms of use. Such is the role of assumptions: suppositions state the essentials in any application. But we have no access to fundamentals in a world of dynamic complexity. All we have to guard against blindness is a use of multiple lenses, with their alternative views.

The real world is interdependent. We have no claim over ‘right essentials,’ but only a path through each moment. Every act ripples outward forever, though we see few effects. The better the fit of our models to use, the more efficient we are. ‘If all we have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail!’ The more tools we use, the more situations we can embrace. Multiple models increase the chance of fitting them properly to applications. A pluralistic approach should be the norm; its absence suggests something wrong.

III. The Nature of Social Relations

From our earliest time, people organized in groups. These systems stem from many origins. Single approaches are problematic if full understanding is sought. ‘If all we have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.’ How might we characterize this hammer?

First comes substitution. Interdependence has two flavors, substitution and complementarity, negative vs. positive feedbacks. Substitution asserts a basic conflict of interest in our relations; there are ‘trade-offs in everything,’ economists like to say. We choose on a continual basis, so can lose more than we gain. But is substitution general or special? What about complementarity?

In nonmaterial realms, scarcity rests on belief. When information or love is shared, the total for all increases. This is a realm of complementarity, where abundance spreads contagiously across social milieux.

With your well-being aligned to my own, competition undermines need: the optimal organizational form here is cooperation. Consider rivalry in a family, or within a team or firm. Competition is doomed to fail among complementary goods.

Substitution and decreasing returns with rising cost of production is central to orthodox theory. Increasing returns sweep us into unfamiliar realms where cooperation is efficient. Complementarity and increasing returns subvert traditional models, so are resisted and not explored. The outcome manifests in economists’ stolid dismissal of any alternative: ‘If all we have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.’

But concerts of value rise with intangible goods such as love and information. Increasing returns bring complementarity into material goods, suggesting orthodox standards only apply to short-term events. Is substitution a special case in a complementary world, as Kaldor (1972, 1975) proposed? Why do we only use hammers? We need new wrenches and drills.

IV. A Network Model for Economics

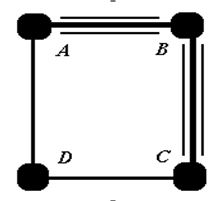

Figure One

Figure One

A transportation network captures systems spanning complementarity and substitution. Aggregation by industry imposes substitution, pushing complementarity out. There is no room for ‘pretzels and beer’ or ‘wine and cheese’ save as special exceptions. A broader reach is needed to incorporate interdependence.

Consider a network composed of four routes in a square relating four towns. How are AB and BC linked? Are their rewards in conflict or common?

The answer rests on direction of traffic: for travel between B and D, they are rivals, but between A and C, complements. Networks show a nondecomposable mix of both relations. Some routes are joined, while others are rivals: we cannot claim substitution.

Once we accept this mix, the issue is organizational form. With only a hammer we use competition and wonder why systems fail. But with increasing returns, cooperation is sought. How do we untangle this?

One way to assess a group is through individual vs. joint pricing. A traditional industry yields a case where joint exceeds single pricing. When joint prices are lower, we have net complementarity. This is a way to think about groups without any industry ploy. Planning horizons supply a means to resolve an institutional choice.

V. The Notion of Planning Horizons

Decisions are made on imagined projections standing on theories selectively blind. We cannot see any issues sequestered outside our focal lens. These projections have a range we call the planning horizon, delimited by surprise. So planning horizons signify our reach of expectation; no unrealism is allowed. Planning horizons only extend through accurate anticipation.

The closer the fit of models to use, the longer our planning horizons as an index of rational limits. Their temporal range is the time-horizon, as one dimension thereof.

Longer-run curves in economics are flatter than their short-run equivalents. If so, the greater the planning horizon, the more elastic is demand and the lower are unit costs, so the less the market price. Longer horizons enhance efficiency in the use of resources.

Planning horizons also reveal an interpersonal linkage in another relation of interdependence we call a ‘horizon effect.’ Horizon effects are ordinal changes; we cannot know how far they move, but only in which direction. Horizonal adjustments spread through interpersonal impact.

Planning horizons shift together in a contagious way. You represent a disturbance term in my imagined projections, just like I interfere in yours. If you extend your horizon, I can plan better too. The contagious spread of horizon effects shows interhorizonal complementarity; our planning horizons adjust together.

VI. The Interdependence of Pricing Decisions

Interhorizonal complementarity is a new form of interdependence. Systems theory according to Senge (1990, pp. 79-80) has three elements: negative feedback (substitution); positive feedback (complementarity); and time (planning horizons). Planning horizons also resolve the institutional problem of competition or cooperation. As substitutes and complements are inextricably bound together, how do we organize incentives to maximize social welfare? Competition and cooperation are incompatible systems. How do we choose?

Longer horizons improve efficiency, and horizon effects spread. Greater horizons tip the balance of interdependence to complementarity from substitution: they shift efficiency over from competition to cooperation. Longer horizons move our relations away from substitutional tradeoffs into closer alignment. The more mature and developed we are, the better cooperation works.

Cooperation engenders horizonal growth as learning is complementary; your education will benefit me. Knowledge is a public good. When competition splits us apart, it also impedes learning. Like collusion of wine and cheese, cooperation cuts price, raising output through the capture of otherwise external profit effects.

In complementary education, competition reduces output directly and through horizon effects, supporting a myopic culture. The virtues of competition are based on substitution assumptions. Models unfit to their applications squander resources. Their impact matters.

VII. Ecological Applications

An ecological system is a case for horizonal theory: all human-caused ecological losses are horizonal. Competition fails in a complementary setting as separation truncates efficiency. Ecological health calls for holistic constructions, to protect integrity. We should forego hammers and nails and treat the earth as a flower.

Instead we impose market solutions and wonder why they collapse. Orthodox substitution assumptions do not apply among complements. We cannot see opportunity costs. Mainstream models attack collusion, and we uphold this story due to an educational failure.

VIII. Educational Applications

The hegemonic control of economics by neoclassical zealots stems from competition. Academics stand against change; alternative views are a threat. This is no learning community.

Learning ought to invite diversity in new angles of vantage. We cannot see outside our own outlooks. This is a case for multiple models, where rivalry yields failure. Education – like ecology – is a complementary setting. Here value is denied and not advanced by orthodoxy. A reluctance to question diverts awareness with taboos against method, history of economics and economic history. Information networks suggest additional losses.

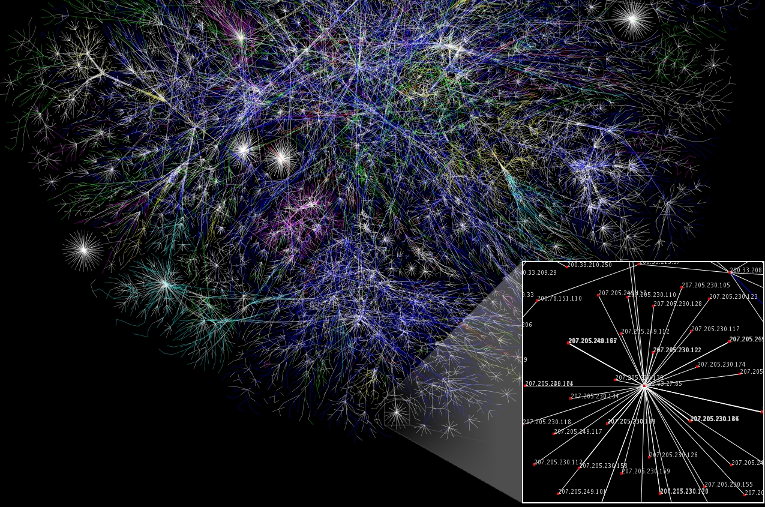

IX. Information Networks

The ICT revolution offers another view of economics. In neoclassical theory, substitution is central. A traditional linkage of value to scarcity illustrates slopes of supply and demand curves. Scarcity yields value; ‘rarer’ means ‘dearer’ in price.

This is untrue in an ICT world. As one observer remarked (Matthew 2001, p. 2): “In the networked economy, the more plentiful things become, the more valuable they become.” As Elsner (2004, p. 1032) put it: “The ‘new’ economy … bears little resemblance to … conventional … scarcity,” justifying collaboration. Any analytical shift to positive feedback is stark, creating a recursive flip in the normal linkage of value to scarcity. Efficiency moves from competition over to cooperation.

X. Social Culture

Because of erroneous substitution, cultures suffer disruptive effects. If frameworks are rigidly held, we cannot see outside their scope; pluralism becomes our only protection against such screens. Outlooks are blind to what they omit, shielding our ignorance from us. Acquisitive values fail under increasing returns. Competition is inefficient due to horizon effects. As some wise soul once said: “Fish discover water last” (McGregor 1971, p. 317).

The social cultures of competition and cooperation are incompatible: cooperation thrives on trust and generosity in our relations. Competition encourages selfish advantage and opportunism, promoting opposition. Orthodox habits are hard to confront. The problem is exacerbated by a rejection of pluralism, because innovations – such as horizon effects – stay invisible. We are blind to our exclusions. Economists’ theory of cost demands a more adaptable lens.

XI. The Case for Openness

Learning communities see in novelty an opportunity and not a threat. If so, openness is an axiom for any proof or reasoned debate. Self-promotion is pathological. We are so used to opposition, we do not see educational loss. We must step beyond orthodox screens to know our rational bounds. The more diverse our tools, the more likely they will fit.

There is no place or role in academics for ruling orthodoxies. Openness should be axiomatic. Until dogmas appear remarkable, their institutional roots survive. Competition is inefficient by keeping horizons short, thus supporting catastrophe. The emperor has no clothes…

XII. Summary and Conclusions

Orthodoxy in academics is symptomatic of failure. That dogma is the norm makes the problem irresolvable except through alternative views. This makes openness axiomatic. Unexplored options stay invisible; we only know opportunity cost through a theoretical lens. The mainstream model limns competition as socially beneficial, with no heed to horizon effects. If frameworks cannot bend, they break. A horizonal frame opens standard theories in novel ways. Is it not time for renewal?

The institutional legacy of competition will haunt us for years. These insights should be obvious, shorn of orthodox screens. Increasing returns and complementarity unfold these doors. Pluralism – much like openness – is axiomatic. Rigid dogmas should be rejected.

The implied shift of education away from competition demands attention. Interhorizonal complementarity offers hope as well. All we can do is change ourselves, through personal growth. The horizon effects from maturation will likely emanate outward. With complementary interdependence, private actions have social effects. If so, we should open to understanding; otherwise we fly blind. ‘If all we have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.’ There is a wide array of new construction needed in economics.

REFERENCES

Elsner, Wolfram 2004, “The ‘New’ Economy: Complexity, Coordination and a Hybrid Governance Approach,” International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 31, No. 11/12, pp. 1029-49.

Kaldor, Nicholas 1972, “The Irrelevance of Equilibrium Economics,” Economic Journal, Vol. 82, No. 327, December, pp. 1237-55.

_____ 1975, “What is Wrong with Economic Theory,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 89, No. 3, August, pp. 347-57.

Matthew, Angus 2001, “The New Economy – Truth or Fallacy?” in Pool: Business and Marketing Strategy, Issue 13, Winter, http://www.poolonline.com/archive/issue13/iss13fea4.html.

McGregor, Douglas 1971, “Theory X and Theory Y,” ch. 16 in D.S. Pugh, ed., Organization Theory, Penguin, New York, pp. 358-74.

Senge, Peter M. 1990, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Doubleday-Currency, New York.

Teaser photo credit: Partial map of the Internet based on the January 15, 2005 data found on opte.org. By The Opte Project – Originally from the English Wikipedia; description page is/was here., CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1538544