The three questions Democrats are asking themselves these days are:

- Can we afford not to pass an infrastructure/climate bill before the end of the year?

- Can we do it on our own, i.e., without Republican votes?

- Will Senators Manchin (D-WV) and Sinema (D-AZ) agree to vote for a reconciliation bill that includes many of the climate and family provisions in the American Jobs Plan?

For readers in a hurry, the answers in order are no, possibly, and that’s a really good question.

For readers with a bit more time, allow me to elaborate.

Can the Democrats afford not to pass an infrastructure/climate bill before the end of the year?

The running joke in Capital City for the past four and a half years is that every week is infrastructure week. It’s agreed by both Republicans and Democrats that US infrastructure is in woeful condition.

The World Economic Forum ranks US infrastructure 13th overall in the world behind Singapore (1) and countries like South Korea (6), Germany (8), France (9), and the United Kingdom (11). It lists the US as 24th in the transition to renewable energy.

Biden ran as the “Build Back Better” candidate—a phrase picked up by most Democratic candidates running in the 2020 election. In a time of a pandemic-induced recession, the promise of jobs and an expanded notion infrastructure that includes high-speed broadband, upgrading childcare and educational facilities, and solidifying the infrastructure of the nation’s (home) caregiving economy, the Democrats offered an ailing nation a stark contrast to Trump’s dystopian vision.

The latest poll by Morning Consult shows the Biden plan supported by 52 percent of all voters compared to the $1 trillion counteroffer brought to the White House by Senator Capito (R-WV) in early June. Biden’s plan has consistently garnered the support of over 50 percent of all voters. It appears too that voters are more enthusiastic about Biden’s approach—including paying for it by taxing corporations and closing loopholes that allow the mega-rich like Trump to pay no income tax—than they are about the Republican alternative. (See Figure 1)

Things have changed since the poll was taken—notably the rejection of the Capito offer and the current bipartisan group of 21 (G21) senators that will be proposing a new alternative with a price tag of around $1.2 trillion.

For the Democrats, there’s too much riding on the passage this year of an infrastructure plan to go into 2022 without being able to say they’ve made good on their promise. It brings us to the next question.

Can we do it on our own, i.e., without Republican votes?

Senate Democrats can pass an infrastructure plan without Republican support, but it won’t be easy. First, they would have to do it through budget reconciliation, as they did with the American Rescue Plan.

The major problem with using reconciliation for infrastructure is the recent ruling of the Senate parliamentarian, who’s said the Democrats have only one bite left of the apple. If they decide to use the process, they will have to combine infrastructure with everything else Mr. Biden has for them to do. It means a bill of at least $4 trillion.

Second, Schumer, Pelosi, and the president would have to find some way to get Senators Sinema and Manchin on board. Both moderates are on the record saying they want a bipartisan infrastructure plan. Senator Sinema is attempting to broker the G21 plan.

The plan’s specifics haven’t been made public; the talk on Pennsylvania Avenue is the proposal will cost between $950K to $1.2 trillion—a far cry from Biden’s original $2.1 trillion plan. There are significant hurdles to be jumped before Biden and progressives in both the House and Senate would accept the G21 plan.

How will the plan be paid for? Republicans have been calling for an increase in the gas tax. The increase, in this case, would come about through indexing the current tax of 18.4 cents per gallon to inflation. The gas tax has been a tried-and-true source of funding for conventional infrastructure items like roads and bridges. The tax hasn’t been raised since 1993, and the president’s plan is hardly conventional.

The president has been clear in his opposition to raising the gas tax. The tax is considered regressive in that all income levels pay the same amount. Moreover, Mr. Biden has promised no new taxes.

In the overall scheme of things, the gas tax—at twice its current amount—wouldn’t begin to pay for the cost of even the G21 proposal. The tax at the current level hasn’t covered the the cost of roads and transit since 2008.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that bringing the tax up to 33.4 cents per gallon and then indexing it going forward would raise $291 billion between 2023 and 2031. If the sum weren’t already paltry enough, shortfalls in the Highway Trust Fund would need to be covered, leaving only $95 billion of actual funds.

One of the arguments for an increased gas tax is the rising number of electric and hybrid vehicles on the road. Greater efficiencies and the loss of the internal combustion engine may be good for the environment, but it’s hellish on gas tax revenues. It is an issue the states are having to grapple with as well. Some are charging much more to register an electric vehicle than a conventional fossil-fueled one.

Assuming the problem of funding for the G21 compromise plan can be solved, the next issue is what happens to the climate and social infrastructure elements of the president’s original proposals. They could, of course, just be left on the cutting-room floor.

Right, the progressives would never allow that to happen—at least not without a fight. We are now presented with the third really good question the Democrats are asking themselves.

Will Senators Manchin (D-WV) and Sinema (D-AZ) agree to vote for a reconciliation bill that includes many of the climate and family provisions in the American Jobs Plan?

Bear with me for a moment as I get a bit into the procedural weeds of the Senate. It’s critical to understanding all the maneuvering currently going on Capitol Hill.

Unlike the House, which only requires a simple majority to pass legislation, 60 votes are needed in the Senate for a bill to be brought to the floor for debate and a vote.

Why 60? It’s the number needed to end a filibuster. Most legislation can be passed with a simple majority once the filibuster is no longer an issue.

The 800-pound exception in the Senate is a budget reconciliation bill. It can be passed with a simple majority. The Rescue Plan mentioned earlier was a reconciliation bill that received 50 Democratic and 50 Republican votes—with the tie being broken by Vice President Harris. It’s the only time the VP is given a vote to cast.

Senators Manchin and Sinema have pretty much shut down any possible change to the filibuster. They’ve also “strongly suggested” an unwillingness to support a partisan infrastructure bill. It means that for a reconciliation to pass, two Republicans would need to replace the two Democrats. As they say in mobland, fuggedaboutit.

What’s being discussed now is pulling out the central climate and social infrastructure elements of the Biden American Jobs Plan and passing a bipartisan infrastructure bill in the range of $950 to $1.2 trillion. The climate and social infrastructure elements would then be packaged as part of the one reconciliation bill that the parliamentarian has said is still available. Would this be a sufficient intervening action that could provide Manchin and Sinema the needed cover for breaking their bipartisan promise to their constituents?

Progressive members of both the House and Senate appear to be demanding in return for their support of a hollowed-out bipartisan infrastructure bill passage of the reconciliation bill. This too is complicated.

Once upon a time in Washington, it was possible to strike such a bargain without much difficulty. These days trust in politics is at a premium—particularly when one of the parties has described an armed attack on the Capitol as nothing more than a “normal tourist visit” and refused to accept the result of a free and fair presidential election.

Suspicious of their Senate colleagues, progressives like Senators Sanders (I-VT) and Markey (D-MA) are hinting they will only go along with such a deal if the reconciliation bill comes first. As no Republican is likely willing to vote for the reconciliation, the full burden will rest directly on the backs of Manchin and Sinema.

Both will have to decide whether they trust the progressives enough and can explain to their constituents why they’re going back on their words of unwillingness to support a partisan bill that will run into the trillions of dollars. Complicating things further, the White House has gotten more strident in its negotiations with Congress in recent days.

And, of course, there is still the House to consider. Whatever happens in the Senate, a bill will still need the concurrence of the lower chamber where it would take no more than four progressives to say no deal.

Although progress is being made in the discussions within the G21, we’re a long way from any resolution. All that can be said for the moment is to buckle up as there’s a rough ahead.

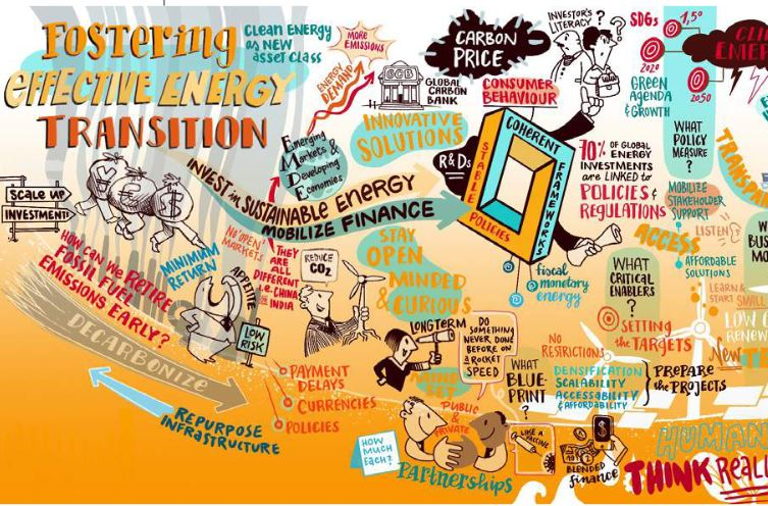

Lead image: World Economic Forum