Students and scholars of steady-state economics must have noticed, by now, that the Degrowth movement in Europe has attained far more traction than the steady-state movement has in the USA (or anywhere). Degrowth is the banner under which thousands have assembled at numerous conferences for almost two decades now, demonstrating a durable unity. Major European news outlets such as The Guardian report on Degrowth doings; even prominent American outlets including Bloomberg have taken note. European degrowthers deserve credit for the energy, passion, and scholarship that has brought them a palpable political presence.

Meanwhile, steady staters in the USA ply their wares among lesser venues in which economics, ecology, and ecological economics are the primary topics. Media spots have been rare and limited to alternative media such as RT and the short-lived Al Jazeera America. Not even PBS covers steady-state economics. Unsurprisingly, then, our presence is way off the political radar. It seems a bit ironic, too, because policy objectives (the ultimate concern of politics) have long flowed from steady-state economics.

Despite the irony, it’s not random coincidence. There are numerous reasons—mostly historical, cultural, and political—for the greater and/or earlier success of the Degrowth movement in Europe. Consider a few:

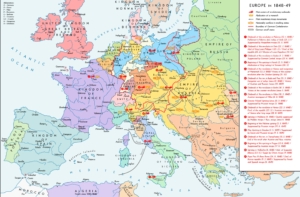

Revolutionary spectres—not all communist—haunted Europe in 1848 when the Communist Manifesto was published. (Image: CC BY-SA 4.0, Credit: Alexander Altenhof)

- The capitalist, pro-growth mindset is more firmly entrenched and powerful in the USA. It permeates the nation, from Wall Street to the media and even to the boards of “environmental” organizations.

- Europe has a rich tradition of heterodox economics (most notably Marxism and the Austrian School) while neoclassical economics is about all you can find in the States.

- Political revolutions of all shapes and sizes have dotted the map of Europe, often borne out of critical economic thought.

- European academia—where students learn and revolutionaries are borne—is less rigidly structured and more open to critical thinking.

- Viable Green parties in Europe offer a political beachhead for degrowthers.

And of course, linguistically and rhetorically, “Degrowth” has the edge over “steady-state economics,” “steady-state movement,” or “steady statesmanship.”

Finally, let’s remember that Europeans have bumped up against limits to growth for centuries, resulting in uncounted skirmishes, border conflicts, pan-European and even world wars. Meanwhile, North American explorers and then the first non-native “Americans” were finding open frontiers “thanks” largely to a Native American holocaust of genocide and smallpox (wrought by Europeans looking for land to colonize). As a result, Americans experienced an economy that was seldom stymied for long until recent decades, while Europeans have been thinking about limits to growth since Malthus and Mill.

It’s Complicated

Little can be done about the facts outlined above. American steady staters are stuck with American history, culture, and politics. Yet, in a very real sense, steady staters have helped empower the Degrowth movement and vice versa. Our overlapping efforts are unified with the slogan “degrowth toward a steady state economy.”

Or are they? In a European context, the answer would seem to be “it’s complicated.” For starters, the Degrowth movement is complicated all on its own. Consider the spectacularly detailed Ph.D. dissertation of Timothée Parrique, The Political Economy of Degrowth. If you wade through the 872 pages, you’ll encounter the “five currents” of Degrowth, the eight “mutually reinforcing changes” comprising Degrowth, and a “map” of the Degrowth territory. You’ll also find 58 definitions of degrowth, plus Parrique’s own synthesis.

Parrique has these currents, changes, and definitions mapped out in his mind, which makes for enlightening podcasts, including several episodes at The Steady Stater. Unfortunately, not everyone gets to apply a Ph.D. program’s worth of focus on the complexities of the Degrowth movement. It’s a shape-shifting movement over time, among countries, and among particular mindsets in European political economy.

That said, the focus henceforth is what an American—or perhaps an anywhere-except-Europe—Degrowth movement might look like.

Steady Statesmanship and European Degrowth: What’s the Difference?

The first-level distinction between steady statesmanship (pursuit of the steady state economy) and the European Degrowth movement is that the latter supposedly has little to do with the trend in GDP. The capitalized term “Degrowth” has been commandeered by European degrowthers and, by their urging, serves as a proper noun to specify a broad political movement. If we are simply talking about a shrinking economy, however, then Parrique suggests we use the hyphenated, non-capitalized “de-growth.”

Heck, why not? De-growth it is! Let’s keep this in mind going forward, at least in this article: “Degrowth” is the political movement, while “de-growth” is decreasing GDP.

To elaborate on the political movement, Parrique defines Degrowth as “a counter-ideology… an ideology nonetheless,” even though it is “perhaps more pluralist, decentralised, and flexible than the great ideologies of the 20th century.” Once you’ve had a moment to digest that, let’s fill in the blanks with Parrique’s additional points in parentheses: “a counter-ideology (which I call a utopia) that even though perhaps more pluralist, decentralized, and flexible than the great ideologies of the 20th century (neoliberalism, capitalism, communism, or Keynesianism) remains an ideology nonetheless.” So Degrowth is an ideology to replace the unjust and unsustainable ideologies of the past. The adherents to this ideology comprise the Degrowth movement.

The pursuit of a steady state economy, on the other hand, is anything but ideological, counter-ideological, or utopian. It’s a simple policy goal, albeit a profound one. It’s all about stabilizing the size of the economy; that is, stabilizing population, production, and consumption. A steady state economy could conceivably be the goal under a constitutional democracy, socialist republic, communist state, kingdom, or tribe. The fact that any type of ideologue—or pragmatist for that matter— can logically strive toward a steady state economy is a good thing for steady staters!

That’s not to say that pursuing a steady state economy is vacant of ideological implications; surely some ideologies are more conducive to a steady state than others. Democratic socialists, for example, are less growth-oriented than free-market capitalists. The complicated part of the story is that an ideology—Marxism for example—may be more conducive to a steady state economy in some regions of the world than in others, and at certain stages in history. Chinese Marxists, for example, can be exceedingly pro-growth, while Cuban Marxists (today at least) may not be. Yet Chinese Marxists could become bona fide steady staters later in the 21st century.

One thing is clear: The steady state economy is all about stabilizing the size of the economy. It’s the original “doughnut economy,” rolled out as a breadstick. Ideally this stabilization happens peacefully and in plenty of time to prevent the catastrophes wrought by the pursuit of perpetual GDP growth. The longer we put off pursuing a steady state economy, the more de-growth is required to attain a sustainable level.

Meanwhile the de-growth must occur with or without political Degrowth, evidently, given the latter doesn’t seem to concern itself with GDP.

Marxists: Boots Off at the Shore, Please

Europeans tend to accept the tenets of socialism more readily than Americans. While the reasons are numerous and historic, the most overlooked one is that polities approaching or experiencing the limits to growth encounter a greater need for socialism. Indeed, as limits to growth result in conflict and social strife, laws and institutions are required to keep the peace. Many of these institutions are or resemble “socialist” developments. In the USA, for example, we have social security, national forests, and Obamacare.

Whatever the reasons, the main point is that socialism is an especially European thing, reflecting to a large degree the Marxist legacy in European politics.

In North America, there’s little quarter for Marxist ideology. It’s not a huge loss, either. Das Kapital may have been paradigm-shifting in the 19th century—kudos to Marx—but it is not essential today for understanding the unsustainability of growth-at-all-costs capitalism. More importantly, no one needs the haunting-spectre baggage that comes with the Communist Manifesto. Degrowth toward a steady state economy in the States will have to be accomplished pursuant to the American Constitution. The Constitution can handle it; it won’t abide a Marxist revolution.

Marx’s monument in Moscow: There for a reason. (Image: CC BY 3.0)

And if we can’t get America on board with de-growth—plus non-Marxist Canada, Brazil, and Australia among others—how’s that going to work for the rest of the world?

This isn’t to discourage the Degrowth Marxists operating in Europe, but the key phrase is “in Europe.” Europe has that aforementioned history of economic and political thought, including Marxist thought and debate from the days when it was fresh off the pages of the Manifesto. Europeans can drink Marxist politics with a firehose. On the other side of the pond, though, and perhaps in the post-Soviet countries of eastern Europe, advancing a de-growth agenda is difficult enough without bearing the mantle of Marxism.

Profanity and “Propaganda” — No Thank You

In North America there is nothing resembling the European Degrowth movement, and for the reasons sketched above, probably never will be. The best we can hope for is “de-growth toward a steady state economy” with clear-eyed focus on the macroeconomic goal; not a bad thing for sustainability purposes at least. The North American steady state would be a mixed economy with regulated markets handling the allocation of rival and excludable goods such as coffee cups, socks, and bicycles. Scale, or the size of the economy relative to its sustaining ecosystem, must be determined through public policy and planning, informed by the best available science in ecological economics such as ecological footprint accounting.

That said, we do have American disciples of the European Degrowth movement, and they emerge on social media. Compared to the European originals, though, American degrowthers haven’t been quite as deep or effective. Consider for example the following offerings, re-tweets, or “likes” from the Twitter account @degrowUS:

- “please someone help. f— 12 means f— all bastards? why not f— 13? saying that all cops are bastards does not imply that all bastards are cops” [f-words spelled out in the original].

- “All presidents are cops and therefore, by transitivity, also bastards.”

- “don’t imprison the pig, abolish the force.”

- “Maybe covid will live on in the Marine Corps while the pandemic fizzles.”

- “Shit’s getting ridiculous.”

While the final example somehow resonates, I for one have no idea how slanderous profanity is supposed to help with any type of movement, much less the type that hopes to topple the most established goals (such as economic growth) and institutions (such as neoclassical economics) in America.

Liberal use of profanity isn’t the only bad idea. At one of the first degrowth gatherings in the USA (Chicago, 2018), students and activists in breakout sessions focused on developing “propaganda” to sway public opinion. The word “propaganda” was tossed about like some rhetorical badge of courage, with no thought given to the disreputable connotations of “propaganda” or the dubious impressions their “propagandizing” might leave on potential allies. The mix of irony and hypocrisy was lost on the propagandists: They were doing in the service of Degrowth (or perhaps in the service of Marxism) what slick Madison Avenue advertisers do in the service of Growth.

A high percentage of attendees also had virtually no knowledge whatsoever about limits to growth or the need for de-growth. That’s ok; they could have come to learn. Unfortunately, such learning wasn’t popular among these comrades. For them, at least, it was more like a gathering of forlorn Marxists who’d found another venue to cast about in, rather than a group of serious-minded thinkers about de-growth, Degrowth, steady-state economics, or steady statesmanship.

To be fair, I’ve noted but a few tweets and one American degrowth meeting. The broader North American experience has included finer moments: The First North American Conference on Economic Degrowth (Vancouver, 2010) got the ball rolling in a highly productive direction, with plenty of insights from the European Degrowth movement as well as “American” steady-state economics. Hopefully that ball hasn’t veered all the way into the gutter of profanity and propaganda. Going forward, American degrowthers should take the best of what the Europeans have offered—the best and the most viable for North America—and bring it to bear judiciously for the purpose of de-growth toward a steady state economy.

Degrowth, Steady-Stater Style

For steady staters, the issue of the day—make that the issue of the century—is the size of the economy. It’s unsustainably and unmistakably overgrown at $89 trillion (the pre-covid level we’re rapidly approaching again). It must shrink to be sustainable. Until then it will be extinguishing species, killing people, and generally trashing the planet, no matter how “equitably” the destruction can be distributed. We absolutely need de-growth toward a steady state economy.

That doesn’t mean we need a communist revolution, a Soviet Gosplan, or a Chinese 5-Year Plan. How would any of that help? Let’s face it, the trappings of Marxism have been every bit as pro-growth as any capitalist country. That’s why the Soviet Union collapsed; its GDP aspirations exceeded its ecological limitations. That’s why the Chinese economy has been the greatest “contributor” to climate change in recent years; its GDP aspirations have forced greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at unprecedented rates. Among Marxist nations, only Cuba eventually moved toward a steady state economy. Yet nothing suggests it was intentional and it’s fair to ask if they remained Marxists as they adapted to limits to growth.

It’s not that steady staters can’t understand where the European Marxist degrowthers are coming from. Europe provided the original examples of capitalist excess and maldistribution of wealth, so it’s geographically natural that Marx was an early critic of capitalism. It’s also true that capitalism fits like a glove with growth. Yet the anti-capitalist Marx was never about de-growth. In fact, Marx was enamored with the productive capacities of capitalism. He was notably antagonistic to Thomas Malthus, not to mention Henry George. In rejecting Malthus and George, Marx thumbed his nose at population dynamics and the cruciality of land in economic production. That’s hardly a recipe for sustainability.

Steady staters are not afraid to emphasize that population must stabilize for peaceful sustainability to become the alternative to war and other Malthusian scenarios. And war, it would seem, is the ultimate violation of social justice. Yet the social justice-minded European Degrowth movement tends to deny the relevance of population as an issue in need of policy. My guess is that, even though Degrowth scholars are smart and competent enough mathematically, they must avoid the political minefield of population growth conversations in order to remain in the Degrowth club.

Those concerned with social justice have good reason to be wary of population politics. The phrase “population control,” especially, has authoritarian connotations of coercive population control measures such as the One-Child Policy in China. Yet the challenge of population growth can be met with effective, equitable investments in women’s education and empowerment. When Project Drawdown investigated carbon-reduction strategies, they found that the combination of family planning and girls’ education carried the most potential to reduce greenhouse gases later this century.

Given their outsized ecological footprints, the USA and European nations should take the lead in reducing domestic fertility rates and elevating population conversations in political venues. Steady staters and degrowthers have key roles to play in framing this dialog. Steady statesmanship in particular includes a sane approach to immigration issues as well as domestic fertility rates. All the variables of population dynamics must be dealt with, because getting to de-growth with a growing population is like slowing a runaway train while shoveling coal into the firebox. All biologists and ecologists know as much. Regardless of the goings-on in Europe, an American Degrowth movement should recognize the fundamental necessity of stabilizing population as well as consumption. Stabilizing GDP, in other words—after a period of de-growth of course.

If not, it’s just a bunch of propaganda.