This is part three of a five-part essay that highlights lessons from the coronavirus pandemic which could advance the fight for a Green New Deal. Part one (published on Resilience.org here) argues that money is not scarce. Part two argues that control of government policy by wealthy elites tends to produce unnecessary suffering and inadequate responses to major crises. Part three argues that plutocracy is incompatible with serious climate action. Part four explores how the public can easily draw very different conclusions and argues that the climate movement must undertake mass education to ensure these lessons are learned. Part five outlines a broad curriculum containing these lessons and many more.

Lesson 3: Plutocracy Is Incompatible with Addressing Climate Change

The pandemic has illuminated the brutality and inadequacy that often defines wealthy elites’ control over government, and should prompt us to consider whether we can conceivably address the climate crisis under elite rule.

We should start by recognizing the effect that the pandemic-driven economic shutdown had on carbon dioxide emissions. Daily emissions across the world in April 2020 were 17% lower than the previous year—the largest drop in recorded history. In the US, emissions dropped an incredible 32%. At the end of 2020, after scattered attempts to reopen parts of the economy, the full year’s emissions were estimated to have fallen by a record 7% globally and 12% in the US. It is valuable for us to see that rapid cuts to emissions are technically possible. But because they are not a result of conscious changes to underlying systems, the effect is temporary and causes extensive harm.

A carbon budget for keeping warming below 2 degrees Celsius prescribes an annual decarbonization rate of 10% or more for wealthy countries, beginning immediately, until emissions are eliminated around 2040. The unprecedented drop in emissions resulting from the shutdown reinforces an idea over a decade old yet too infrequently acknowledged—the need for economic contraction in addressing the climate crisis.

At least two challenges suggest that in order to keep to our carbon budget, fossil fuel use would need to fall faster than renewables are installed, which would reduce the overall energy available for economic activity. First is the possibility that renewable energy infrastructure cannot be deployed rapidly enough. The large-scale adoption of new energy sources has historically taken several decades, and these new sources piled on top of older fuels rather than replacing them. We can surely speed this up with a concerted effort, but it seems very unlikely that the new energy available from renewables can match or exceed the energy lost from simultaneously closing fossil fuel plants. Second is the reality that fossil fuels are currently relied on for the manufacture and deployment of renewable energy technologies, and speeding up the transition would increase their use at least at the beginning. This would cut into the carbon budget if other fossil-fueled economic activities weren’t simultaneously scaled back or halted. Even as renewable energy deployment is ramped up dramatically, we’ll likely need a well-planned and equitable shutdown of some economic activity to achieve those rapid carbon cuts.

Would we then return to the high-consumption lifestyles to which we’re accustomed after the transition? The answer is a resounding no. There is good reason to think that an all-renewable society will be one with less energy available than we’ve previously gotten from fossil fuels and therefore have a smaller economy anyway. But even if renewables could allow us to maintain current lifestyles, we would need to consume far less to address the other serious ecological crises beyond climate change that are driven by our overconsumption. The energy transition must be understood as part of a broader transformation towards a civilization that operates within ecological limits.

The Green New Deal (GND) is often seen as a “green stimulus,” a massive investment program that will put people back to work in the service of the energy transition. But stimulus programs have historically been used to reinstate economic growth after a recession. It’s easy to overlook the reality that a GND that aims to adhere to our carbon budget won’t generate overall growth but rather move the economy towards degrowth and, ultimately, a steady state. If most earnestly believe that a GND is a growth strategy, it’s possible to imagine many elites outside of the fossil fuel industry supporting it and the public eagerly welcoming it. But the more complicated picture described above calls this support into question and would require activists to lay the groundwork for a climate-driven economic shutdown.

Will corporate elites allow this to take place? Those in power did initiate a closing of most businesses during the pandemic, which may lead some to think they would support another shutdown to preserve a livable climate. But there are unique reasons for the virus-driven shutdown. As coronavirus first began to spread, the costs of shutting down initially seemed greater than keeping businesses open. But when infections started to surge it became clear that there would be no regular economic activity anyway. It was recognized that the country faced an immediate mortal risk which threatened to overwhelm the healthcare system and cause panic—a major threat to business. It began to make more sense to temporarily shut down the economy and prevent the worst outcomes, which would allow profits to return sooner. And when the nation went into quarantine, the industries with the greatest political influence were able to use the need for immediate public relief to win a large bailout.

The shutdown wasn’t a suspension of the economic goal of profit maximization or elites’ pursuit of their self-interest. It just seemed to be the least costly path forward. A survey of prominent economists found that 88% believed we would need to tolerate “a very large contraction in economic activity” to contain the outbreak, and 80% said that prematurely ending the shutdown would lead to greater economic damage than maintaining it. A large number of executives and major shareholders were still not comfortable with closing business, however, and many began pushing almost immediately to end the shutdown. Given the fact that elites reopened the economy in the middle of a surging pandemic, there is no serious prospect that they’ll consider a much longer shutdown around a slower-moving issue like climate change. And because it would effectively entail a transition to an economy that prioritizes ecological health over profit, those in power will have no reason to even consider the transition. There is no need to contemplate the journey if you can’t stand the destination.

If plutocracy is incompatible with adhering to our carbon budget, then only by wresting control of government from the wealthy can we maintain a livable climate. That means electing a majority of representatives willing to enshrine our carbon budget in policy with all the challenges that entails, which will only be possible if activists build sufficient public support for a climate-driven economic shutdown.

At the beginning of the quarantine, the public recognized the deadly threat posed by the virus and accepted that closing business was necessary. After a few weeks some began to protest the shutdown, but polls found persistent majority support for maintaining it. To pursue a climate-driven shutdown, public support must instead be based on a deep understanding of the climate problem and its solutions, undergirded by sufficient funding to meet all basic needs. It must be understood and accepted that certain aspects of the transition, like lower-consumption lifestyles, would be permanent changes in how society operates. But this climate preservation plan would prioritize economic security for all, and it would avoid the other major challenge faced by individuals during the pandemic—isolation. On the contrary, community would be emphasized as we work to reduce fossil fuel use and create a sustainable society.

The shutdown reminds us that though corporate elites can seem all-powerful, ultimately the government determines whether businesses are allowed to operate or not. Corporations are creations of state law. No questions of ownership needed to be resolved; businesses simply had to comply with the government’s closure orders. It just so happened that the orders came from officials primarily representing businesses interests. A social movement in control of state governorships could initiate climate-driven shutdowns across the country, though control of the federal government would be critical for creating the funding needed to maintain them. A democratic wave must sweep the nation, sustained by a public thoroughly prepared for the challenges ahead.

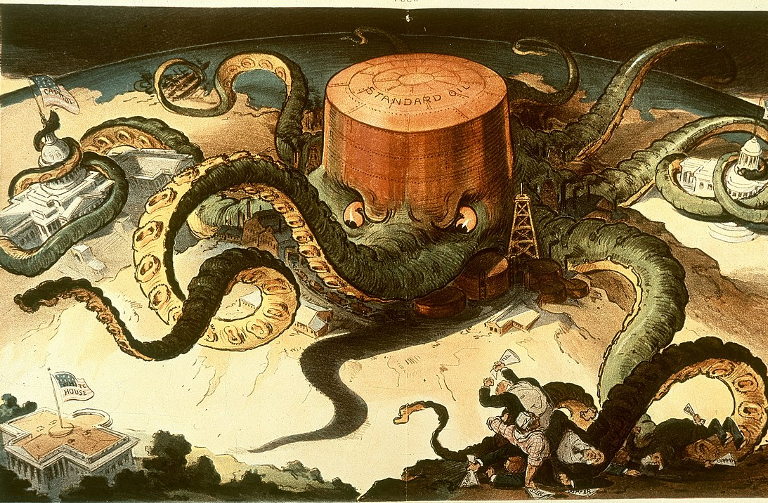

Teaser photo credit: Contemporary nineteenth century depiction of an acquistive and manipulative business enterprise as an all-powerful octopus. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=530376